Sim Chi Yin is a Singaporean photographer based in Beijing, focusing on editorial and documentary work. In June 2011, she was selected to join Vii Photo Agency’s Mentor Program. In 2010, Chi Yin won a Magnum Foundation scholarship for a summer programme in documentary photography at New York University.

In this Invisible Interview, Chi Yin shares with us her experiences, and about Long Road Home, her latest photo book on migrant domestic workers from Indonesia.

Can you tell us more about your background?

I was a journalist with The Straits Times (ST) for 9 years until I left to return to photography at the end of last year. I had covered Singapore social and political news before being sent out to Beijing as China Correspondent for the paper in mid 2007. I started out at the Straits Times’ Picture Desk as an intern photographer when I was an eager beaver 18-year-old, doing extra assignments because I felt so alive just telling stories through making pictures. The newspaper then gave me a scholarship to read International History at the London School of Economics.

How did Long Road Home, your book on Indonesian domestic workers come about?

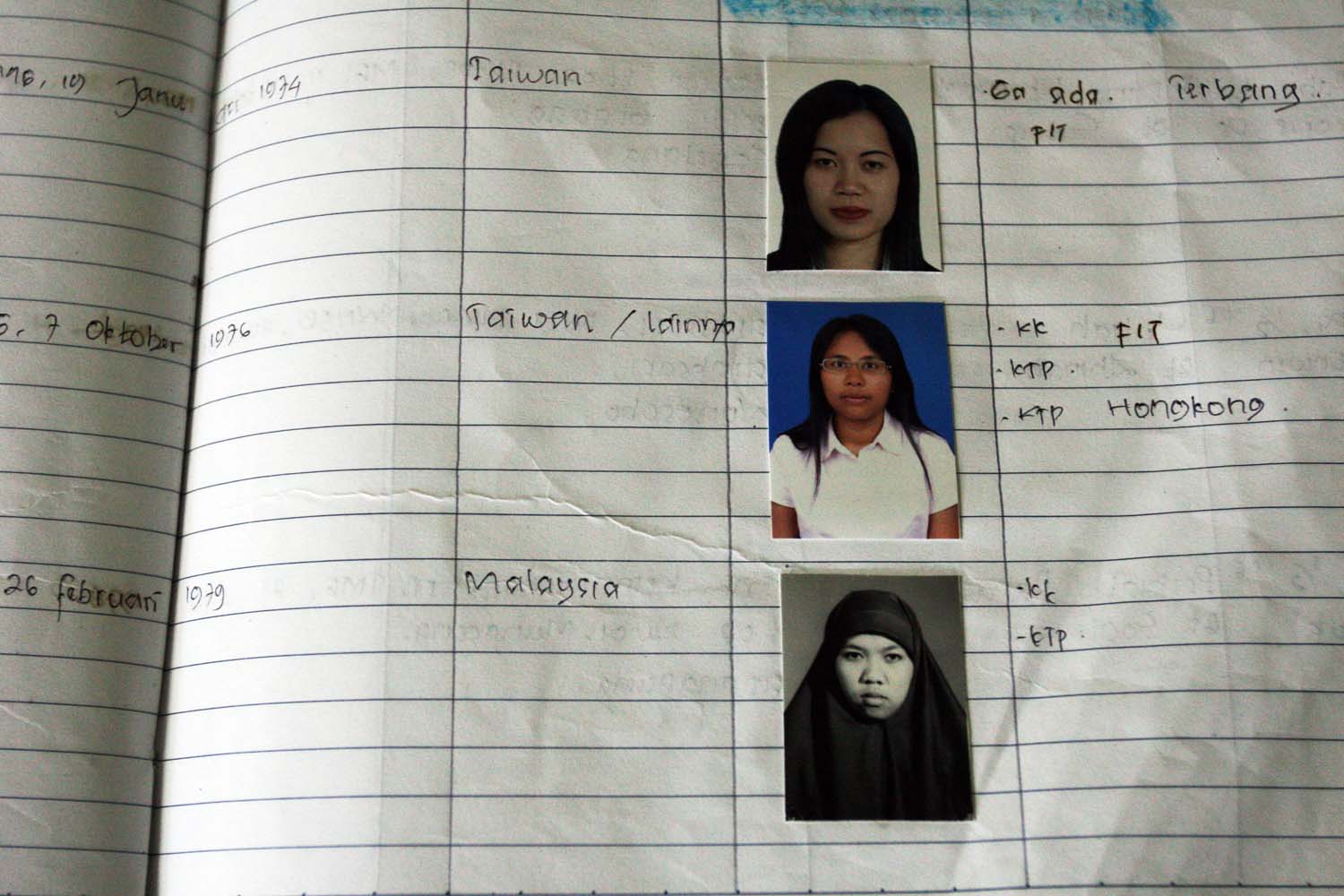

I had covered the social issues in my early years as a journalist at the ST and then the labour beat while at The New Paper for a spell from 2003 onwards. I wrote many stories about migrant workers in our midst – their lives, struggles, truimphs – and their relationship to us as their hosts. In my personal capacity, I was also active in the civil society movement that was blossoming around the same time, pushing for more awareness of these workers in our midst, mounting advocacy campaigns through photography. In both my civil society and professional work on this issue, i was often questioned, challenged: “if things were so bad in Singapore, why do the workers still keep coming?” I felt I wanted to go over to Indonesia to document just why these workers still keep coming. So I did. From mid 2006 onwards, I travelled to Java whenever I had time off work to photograph migrant women workers at each stage of the migration process: finding the local village middlemen, saying goodbye to their families, travelling to Jakarta (or the nearest big city) for training and paperwork, living overseas, taking care of someone else’s family…and also the other end of the migration chain, going home.

How long did it take to complete the book? And can you share with us the photography process, and your experience with your subjects.

There are a few images in the book which date to 2003. But the bulk of images were made between 2006 and 2009 on trips to Java. Getting the funding to publish through the International Labour Organization (ILO), writing up the 16,000 or so words of text and repeated rounds of editing the whole book took right up to weeks before it went to print in mid 2011. I basically made what contacts I could among Indonesian workers in Singapore and asked them for help to link me up with their compatriots back home. I also just went to small towns in central Java and hung out at the local labour bureau to meet workers who were about the leave home to work overseas. Or at small town labour recruitment agencies. I also rode around with recruiters as they hunted for workers to send overseas. I had a great time with most of the women I photographed. Sugiyani, the protagonist in the book is someone I met at a small town labour bureau. She was there to process her paperwork to go overseas to work. Through a friend, I spoke to her about why I wanted to document her story of leaving home and how I will need to stay in her home, be a fly on the wall, have access to her and her family for the following week. I followed up with a visit to her home and met her husband and little girl, and they were very kind to agree to let me hang out in their home to document their final week together. Many of the workers, after hanging out for a while, would ask me if I could take them home as my domestic worker! But I never needed one.

How involved or willing were the employers of your subjects to being documented?

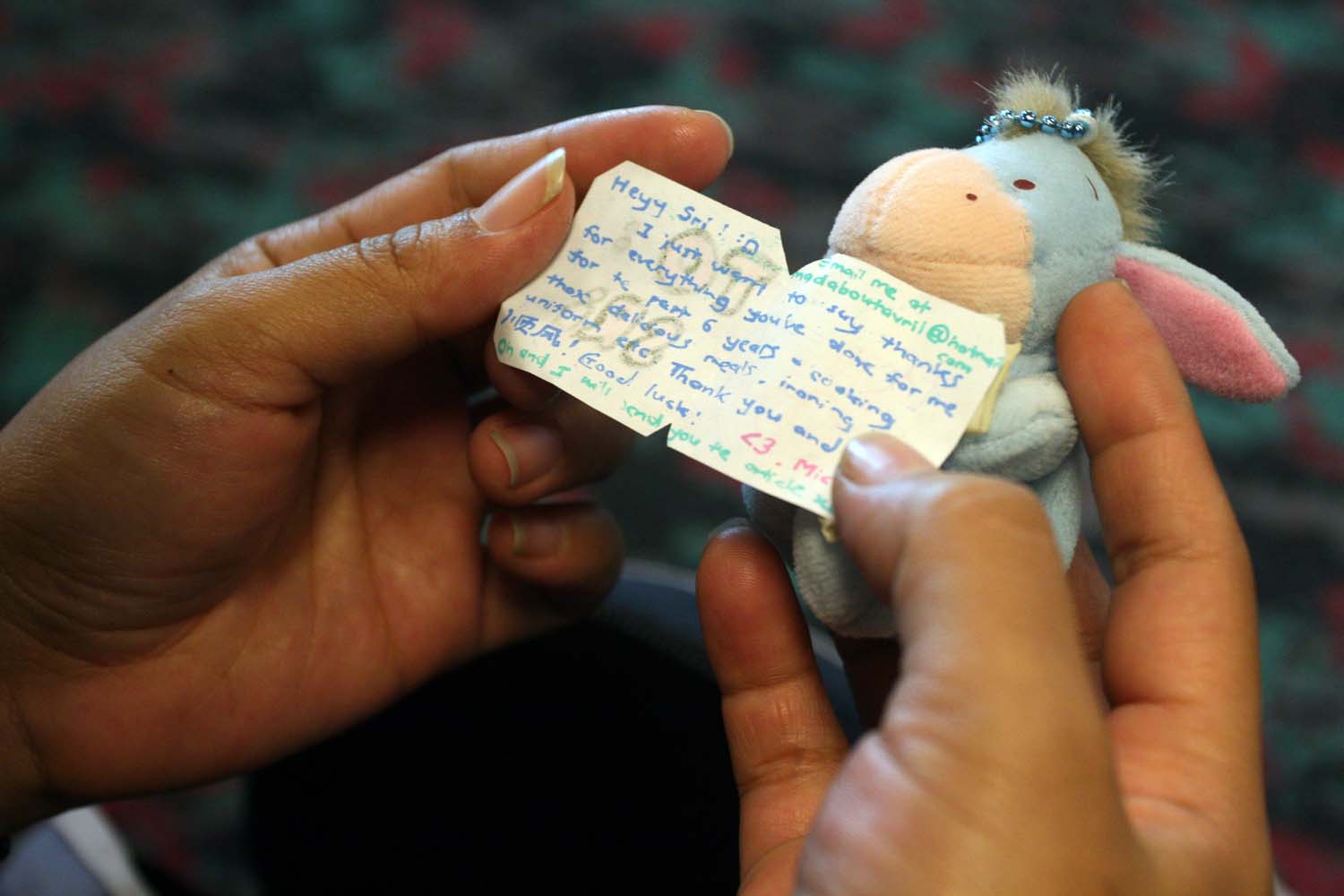

I didn’t shoot too many stories of workers in homes in Singapore because I felt it was something that Singaporeans didn’t need help visualising or understanding. The few stories and households I did shoot: those were all done through friends or labour agents who knew the employers well. So we had no problems at all. I shot the interaction of worker and employer. With Sugiyani, my one big regret was that I wasn’t able to followup with her story when she arrived in Singapore. The agency that brought her in said categorically that her employer did not want her to have any contact with me or the press anymore. We did try repeatedly, but were stonewalled by the agency. So that was that. And then Sugiyani’s husband Warsun changed his phone number and I wasn’t able to reach her family either. Last month, the ILO managed through their contacts on the ground to find Warsun in his home and then brought him and Rola their daughter to Jakarta for the book launch there. That afternoon, I phoned Sugiyani, who is now working in Malaysia after a two-year stint in Singapore, and we chatted. It was great to hear her and to know she’s well and happy.

Do share with us your editing process in compiling photographs for the book. And later, the exhibition.

The pictures were shot over a number of years, so I did edits along the way and had quite a clear sense of how the chapters broke down – in phases of the migration chain – and just kept shooting and editing. I had colleagues and friends help edit the work. With the exhibition, my colleagues and I picked 20 images that were representative of the work and among the visually-strongest of the body of pictures.

You are now documenting migrant workers in China, tell us more.

Migration has been a kind of quiet, sub-conscious thread in much of my work, going back to photographing Roma (Gypsies) in Romania in 1999-2001, Samsui women in 2002-3, Indonesian and Filipino workers in Singapore from 2003 onwards. China is experiencing a huge internal movement of people, the largest on earth. My little stab at it is a series of pictures of migrants who live in basements in Beijing. These will be on Vii’s website soon.

Some of your peers at Straits Times refer to you as one of the most talented photojournalist to come out of the ST stables. What is your secret?

Ah? Hmm. I don’t know if that is true. And there is no secret. I’ve just tried my best to make time to do projects, work with NGOs on issues that interest me, drive me, alongside my job. Much of my photography work was done outside of work, since my job was to be a reporter/writer. Although I took pictures for some of the longer features I filed – from Tibet, North Korea, Myanmar, Cambodia — I didn’t worked as a photographer on Picture Desk once I was back from university and in full-time employment at the paper.

If we read correctly, you were a writer/essayist prior to being a photographer. Why did you switch? And how has your writing skills played a part in your photography pursuits (if at all)?

I started out as a photographer but was unable to make it back to the Picture Desk after finishing university on scholarship and bond. As explained above, I then left my foreign correspondent job to return to my long-neglected mistress, photography, when I could. Reporting skills certainly help when doing photo projects. And I take notes when out on shoots. It’s always handy to have more information, depth.

Earlier this year, you joined the highly sought-after Vii Photo Agency’s Mentor Program. How did that come about and how has that been for you?

I was accepted on the Vii Mentor Program in late June. I was asked to apply by Vii photographer Marcus Bleasdale and I did and then one morning, I woke up and saw an email from Marcus with just the words: “congrats, you’re in!”. It’s still early days yet, but it has been very helpful and valuable to me. Marcus has really been a pillar of support in this first year of freelancing for me, as I’m figuring out this new life. He is also a great human being and role model.

How important is it for a young photographer to have a mentor?

I think those who are blessed enough to have one should grasp the opportunity by the horns. It’s important. It’s a jungle out there. Figuring out how to function in the industry, staying afloat financially while pursuing one’s ideals can be quite a task. So having someone to watch over you when you’re trying to do all that can make a huge difference. I’ve been lucky to also have had Susan Meiselas of Magnum Photos as a kind of informal mentor for some years now. She knows what I’m up to and is a steady, supportive voice and sounding board.

Vii Photo Agency is making industry headlines with their current restructuring – Any comments? Will you be pursuing a future with the prestigious agency after your program?

All mentees, like other photographers, can apply for to join the agency or any other one of their choice after the 2 years on the Mentorship. I haven’t planned that far ahead. I’m just staying focused on doing the work for now. There’s a lot more to be done.

What do you think is the future of photo books?

I’m in two minds about that. I think there will always been a market for photo books. But it may become even more niche than it is now. That said, there are presses making self-publishing easier and I have met so many photographers at the Eddie Adams workshop that I’ve just attended with books that they put out themselves. At the same time, there’s the ipad and kindle etc. and of course multimedia online presentations now and that’s opening up new possibilities. I think it boils down to what each photographer wants – who is your audience, who do you want to reach, what is the intention of your work ? And one will have to go from there to make a choice about what medium to get the work out in. And there’s nothing stopping people from doing things on multiple platforms to reach difference audiences with the same body of work. Cutting edge thinkers like Fred Ritchin – whom I was lucky to spend a couple of weeks studying with last year — argue we need a new form altogether to capture and disseminate the horrors and joys of our world. See his Afterphotography book and blog.

What advice do you have for aspiring photojournalists or documentary photographers?

Find an issue that you really care about, and just go tell those stories. I think projects which show your voice as a photographer will go much further in telling people what you’re about than any number of editorial assignments you may shoot. That’s what I’m reminding myself too, constantly.

If you could travel in time, what year in the past or future would you travel to with your camera?

Perhaps 1965, in Vietnam or deep in the bowels of Cultural Revolution-wrecked China.

More of Sim Chi Yin’s work on her website: www.simchiyin.com

Chi Yin’s book Long Road Home is available for purchase at: http://selectbooks.com.sg/getTitle.aspx?SBNum=052339

Share

Comments 14

Pingback: Featured Young China Watcher – Sim Chi Yin, Photographer and Member of VII Photo Agency | YCW

Very important to encourage more photographers from our part of the world. Bravo!

I have an ongoing project about the sea gypsies of Borneo, Orang Badjau. If you have time hop on to my website to see the photos. http://sunglingun.com/2014/03/22/sea-gypsies-3-sebuan-island/

Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin… http://t.co/LcE2PO2j

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin http://t.co/96V51lGg #photoessay

Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin http://t.co/c3an4TEq

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin http://t.co/6Gi7yF0a

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin http://t.co/6Gi7yF0a

Pingback: Happy May Day, happy no working day! «

RT @invisphotogasia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin. http://t.co/O5iihIE3

Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin. http://t.co/qBLYYzwP

RT @invisphotogasia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin. http://t.co/O5iihIE3

RT @invisphotogasia: Invisible Interview & Photo Essay: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin. http://t.co/O5iihIE3

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin http://t.co/J2iVBrDQ #Indonesia #domesticworkers #photography

Invisible Interview & #PhotoEssay :Long Road Home, by Sim Chi Yin. http://t.co/RaWgkgTD #photography #photojournalism – via @InvisPhotogAsia