“When people ask me about my work I always talk about this work because it is what I am trying to do. It’s called the Great Pretenders. I’m trying to pretend. You know there are a lot of those images of animals that you cannot see but they are there. They are camouflaged. For a photographer to capture those insects is very ironic. It’s like a paradox and very confusing. Is a good photograph of these camouflaged insects when you see it or when you don’t see it? I like the idea and want to challenge this in my photography.”

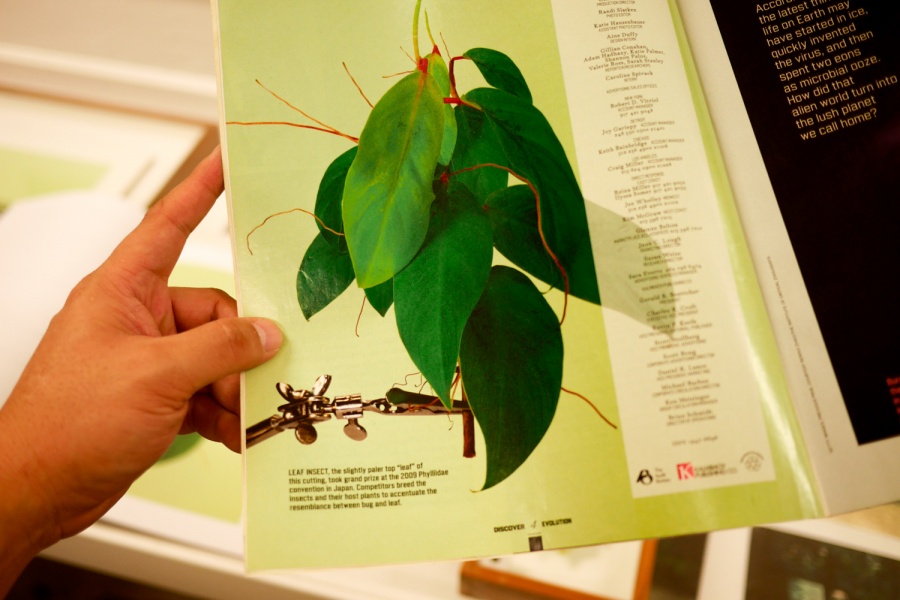

“Basically, I created this idea of a leaf insect competition in Japan where a group of scientists compete every year by mixing the genes of insects with plants. Because every insect belongs to a single plant, they will stay on the plant forever. The scientists try to mix the genes to make the plant look more like the insect and the insect look more like the plant.

So in the narrative, I went to photograph the winners of the competition so there’s all these plates. I have a website too that looks like a science website. And I made a journal with the winner and the runner-ups. But basically there are no insects. Because this is the winner and his insect is so camouflaged that you cannot see it. That’s the whole idea – to make a clue or clues to make you believe there is something on these leaves, but actually there is nothing.”

That was how Robert Zhao introduced me to his playful world of photography when I visited his studio. And Robert’s world is an intelligently mischievous one where trick is the treat, and fiction dances with fact in a skeptical, yet flirtatious visual ballet. His studio, on a fifth floor at Goodman Arts Centre, is just as confusing as the world he portrays. It feels one third science lab, one third taxidermist’s workshop, and final third Peter Pan’s pantry.

Robert Zhao Renhui, or the artist known as Institute Of Critical Zoologists, is without doubt, one of the most prominent young photographic artists in Singapore today. His work has been exhibited the world over and his prints are very well collected.

But how did it all begin?

“I’ve always been interested in how everything we understand about a photograph changes whenever we read something. Like what’s the meaning of all these photographs? What’s the word? We always need a word, or a situation or environment for the image, or these series of images. For me, all these meanings that we create or get away with are quite useless. So for this series, it is about creating meaning out of nothing. We tend to believe in photographs because of the way they are.”

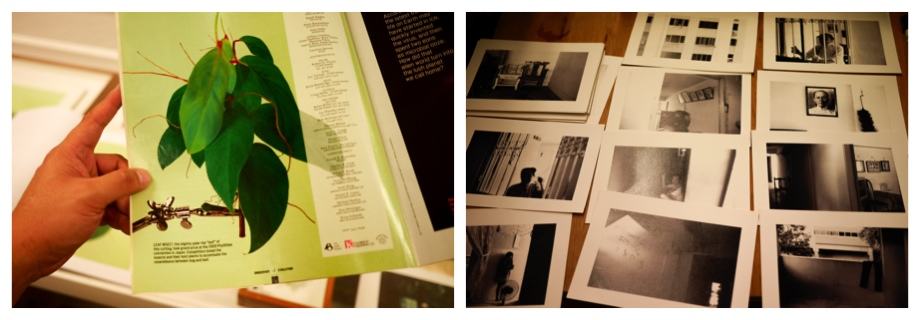

Robert then showed me a Summer 2011 issue of Discover Magazine. Their slogan was ‘Science for the Curious’ and the issue theme was ‘Evolution: Rethinking The Story Of Life”. Inside, on a full page, they had published an image from Robert’s The Pretenders and captioned it “Leaf Insect, the slightly paler top “leaf” of this cutting, took grand prize at the 2009 Phylliidae convention in Japan.” I was told the magazine contacted him after a visit to his website and requested for images rather sternly without asking any questions.

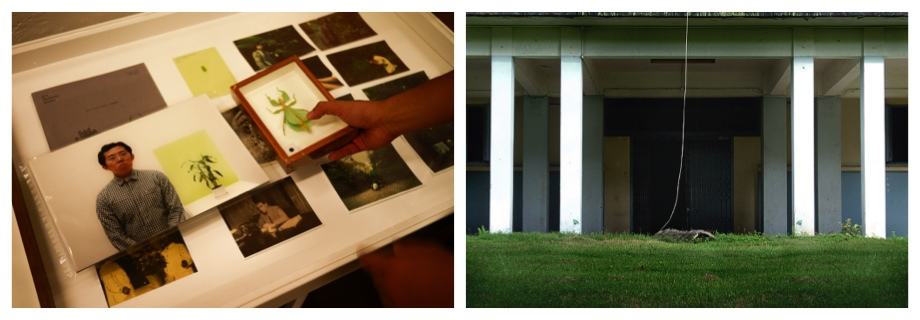

L) Discover Magazine R) One Room Flats

I was then shown a series of Robert’s early documentary photographs on Singapore’s ‘One Room Flats’. He asked me if I had shot that too. I said no. He said ‘everyone’s done it, shame on you’ and laughed. Robert later commented that he didn’t like this work because he only had a temporary connection with the subjects that was simply for his own photography. The project did nothing for the subjects and felt exploitative in retrospect.

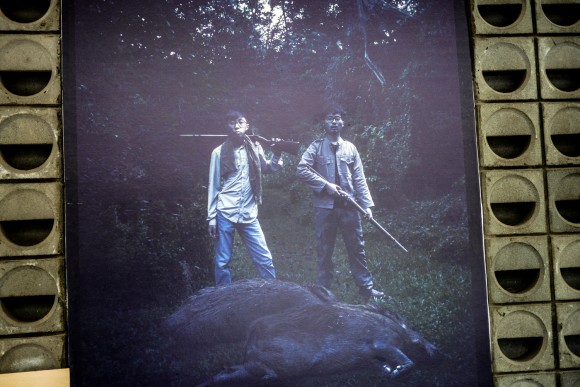

Quite a few years ago, Robert and his friend Ang Song Nian made a body of work called Wu Xiao Kang that was described as a set of 36 photographs taken by a schizophrenic Singaporean photographer who later killed himself. The work proved controversial. Some members of the public responded very negatively after realising the conceptual premise. Needless to say, there was heated debate questioning the nature and role of Photography in Singapore. Although, I have never seen the photographs myself, the idea intrigued me and I was curious.

Where are the pictures and tell me how Wu Xiao Kang come about?

“They’re at home. It’s very simple. Terence Yeung used to be my photography lecturer before Chow Chee Yong. He told me something like this… look at this image. And now look at it again, but this time I’ll tell you that this is the photograph that Song Nian took, or I took before I died. The last picture. Everything about this photograph changes forever. I was like wow. That was it. That is how much power an understanding of something can change an image. I was very amazed and intrigued.

The idea came about from many things. We wanted to talk about madness, about doing something again, and again, and again with no meaning. And about believing in photography. There was a group of us who did the work. We were very young and we were shocked to see the way people reacted because we were just doing what we were doing. The aftermath was horrible. But basically, what I got out of it was you learn to consider the audience and how much they bring away from your work, what they are looking for or expecting, and what you should be foregrounding for them to understand the work.”

Someone mentioned that was the first time in Singapore there was a debate that questioned photography in that manner?

“No lah, I wouldn’t say so. Even right now a lot of people ask me questions like is it real or not? I would answer them, but the ultimate question I would throw back at them is actually, you shouldn’t just be asking me this question. You should also ask Kevin and his work. Whether his intentions of that work is true? You should also ask a painter. All these questions should be exercised on everything that you see, especially in the arts. With everything you have to be cautious. That’s what I think, and a part of my work does that. It tries to make you cautious. It will be good if we never have to write artist statements. Just let our work survive. But it’s very strange that we have to supply statements so people can understand the work. In the ideal world, I don’t want to issue any artist statements.”

So you think it’s okay to look at a photograph or work without any context?

“I think some work, especially some really strong images, you just want to enjoy them. Sometimes, the text makes the image more enjoyable, but personally I like to enjoy an image for what it is, and not be burdened. I mean I use text all the time, but I think it can be a disability sometimes. Because in a way, you are trying to guide a person towards a certain direction, being manipulative with meaning. I think we should be aware of all these structures that are in place when photographers or artists frame their work for us.

A lot of people are obsessed with the truth, especially with photography – it’s the truth mah. For example, newspapers must have photographs so that we know it’s real. This dependency on the photograph as a form of reality is not very helpful in our understanding of reality.”

So tell us about Institute Of Critical Zoologists.

“I was looking at all these institutions that were talking about animal rights and that studied animals. I realised they all had this serious and grand vision of animals. Then I said okay, let’s do something about this. Let’s do something funny. I copied all the text and created this mock institution. That was it. And then I kept on growing the institute. When people asked me what the institute was about, I said I don’t know, I’m still creating the meaning of it.

My tutor Paul Tebbs (Camberwell College of Arts), without him and his advice, my work will not have this kind of direction. And not so strong. The tutor is really important for me. He always helped me link the dots together so I was very fortunate.”

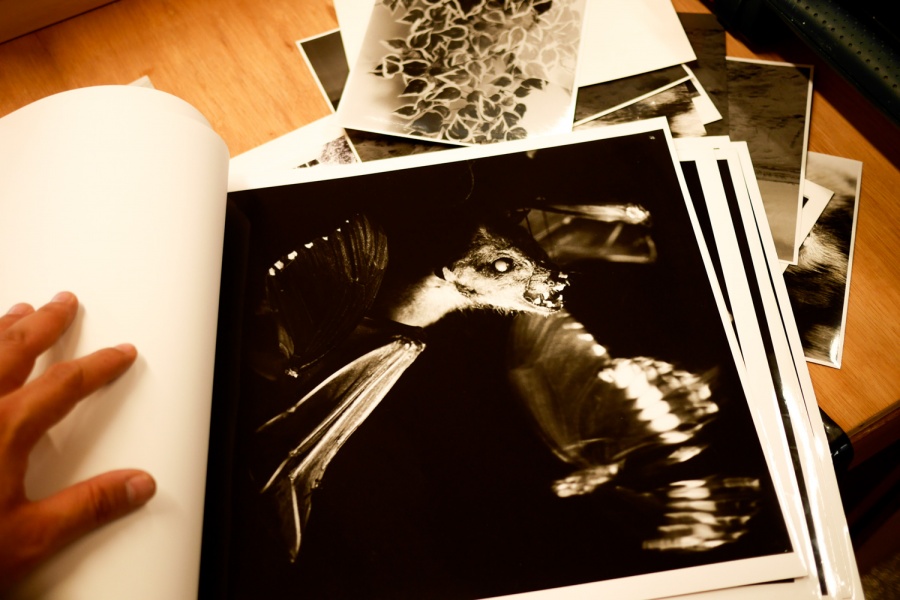

L) The Great Pretenders R) From the series, Wu Xiao Kang, 1979-2009

The conversation then shifted towards Robert’s last straight documentary work of animals in captivity. At some point after creating the work, he said he grew suspicious of the purpose of the images. He found them too emotionally manipulative and exploitative. It was then that he changed his method of working and found a new, less emotional, less predictive way of talking about the same subject.

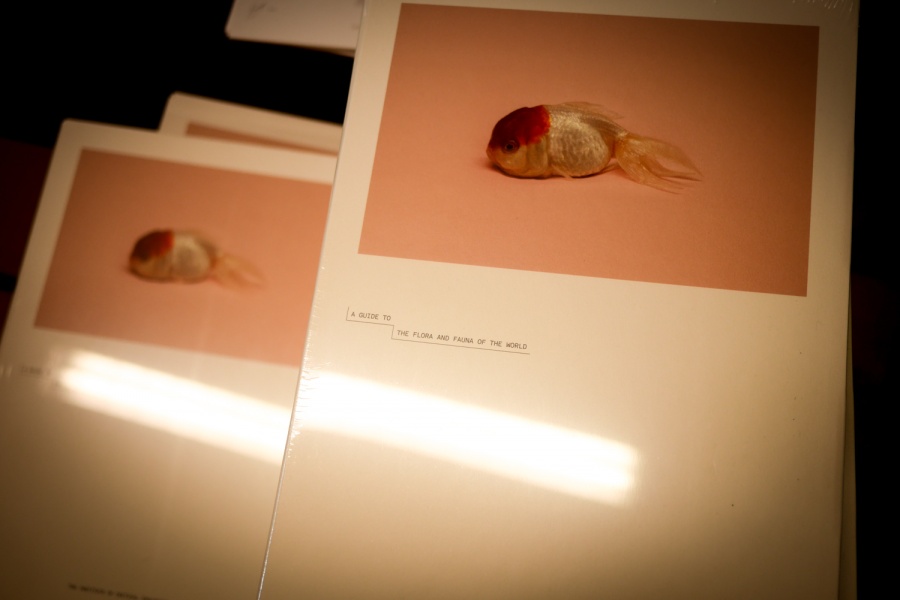

Then like an excited child, Robert shared how he made his photographs. Rubber whales, dead goldfishes, dead birds and roadkill pythons. He’s propped, shot and ‘shopped them all, re-animating each one elaborately back to life in his world of fauna and flora.

So during the conception, do you see the image first or the idea?

“It’s a very good question. I used to have the idea first then I’d try to make an image based on the idea. But then you realise it doesn’t work because the idea is invisible and the picture is very visible. Now I try to create an image that might be bigger than my idea, that can expand the idea to something more than what I may have missed in my research. If I just created an image from a paragraph, it just feels like an illustration of the idea. It doesn’t work.”

Robert on criticism, animals and activism.

“To me, their criticisms is something I do anyway. They say I’m a liar and I’m not honest. It’s true what. (So it’s a compliment?) No, it’s not a compliment, it is what it is. I don’t try to pretend. That’s the nature of my work. My work is not interested in animal welfare. I am, but my work is not trying to foreground any kind of emotional response to animals because emotions stop the conversation rather than expand it. Same thing with anything too emotional. I’m very wary of activists or any form of activism for subjects that are otherwise voiceless.

(Why is that?) Because I think there is something wrong about giving voices to things that need voices because you are assuming that they need voices. I mean I’m coming from an animal rights point of view where we assume we know best, that we should always be doing things for animals. But a lot of times when you look deeper, these people are doing things for themselves. I am really talking from my personal experiences observing how animal activism works and how people interact with animals. It may not be the case for others.”

Do you still enjoy taking simple photographs, without any questioning?

“I have instagram. Haha. I enjoy them, but I don’t do it. I don’t take pictures of my travels, like with my girlfriend. (So you don’t enjoy taking photographs at that base level?) That’s a problem. I don’t. It might be because I am over-thinking a simple act. (So all your photographs now are functional?) Yes, haha. Like when you draw the sword, it must be blood, no sparring. Haha.”

So the last question, I’m about to step into your latest solo exhibition ‘The Last Thing You See’. I don’t know your work, what advice do you have for me?

“That’s a very good question. (Pause) Don’t forget to enjoy the images.”

The Last Thing You See: Recent works by Robert Zhao Renhui Exhibition opens at 2902 Gallery, Singapore from 16th November to 5 January. A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World book by Robert Zhao Renhui is available at http://criticalzoologists.org/guide/

Share

Comments 1

Pingback: Behind the Scenes: Kenny Leck, Co-organiser of Singapore Art Book Fair | English Blog