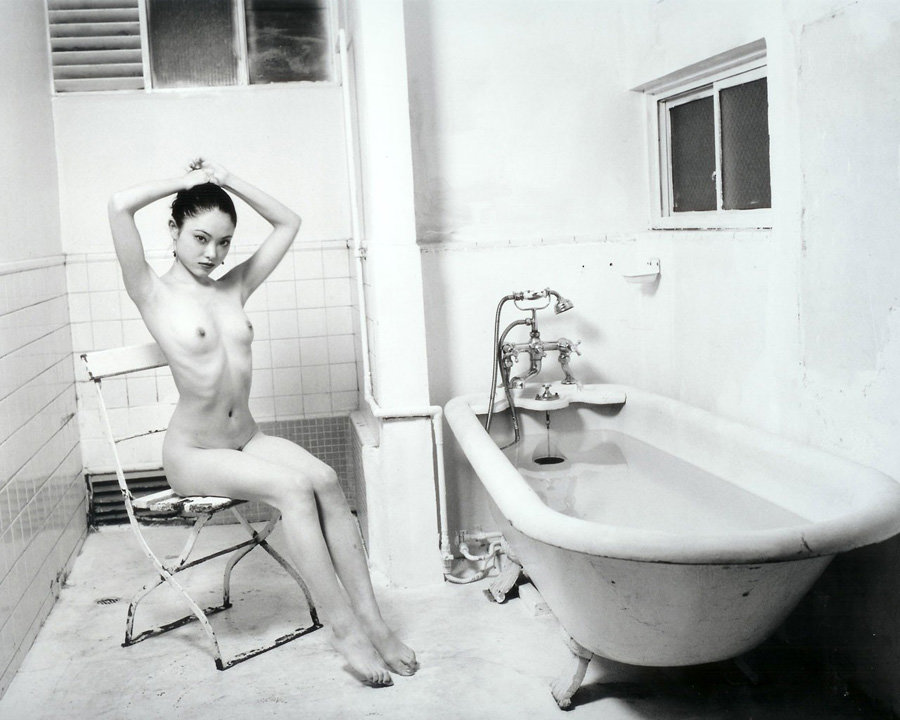

Photograph by Nobuyoshi Araki

This is an old article of Araki’s work, written in 2004 during his exhibitions at epSITE and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in Singapore. Text by Zhuang Wubin.

Nobuyoshi Araki, or Tensai Araki (Araki, the genius), has existed in the grey area of what is taboo and what is art within the Japanese society. The 65-year-old photographer is an enviable man. He takes pictures of nude women, receives love letters in gratitude and sleeps with almost all of them – “A photo shoot is very erotic,” he explains to Nan Goldin in an Artfourm International interview in 1995 – while Japan endears him as an artist and her favourite son.

Although he graduated from the School of Photography at Chiba University in 1963, Araki’s love affair with the medium blossomed much earlier. His father ran a ghetta (Japanese clogs) shop but spent more time doing assignments as a semi-pro photographer, with Araki helping out as assistant. At the university, the curriculum – with an emphasis on photography as science – understandably bored Araki to death. He found himself spending more time at the Kyobashi Film Library watching movies by Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio de Sica.

Upon graduation, Araki joined advertising company Dentsu as a commercial photographer. The enfant terrible regained his freedom nine years later when he became a freelancer. Since then, he has published over 300 photography books and has done retrospectives in Japan, Graz, Frankfurt, London, Cologne and New York, amongst others. Despite his frequent brushes with the law, the sum of his fines over the years is only about 300,000 yen (around US$2800).

“Last Year 2001” is a dazzling juxtaposition of female nudes and sky-scapes. Yoshiko Isshiki, Araki’s manager for the last 10 years, points out that the series is part of an ongoing picture diary – which the photographer publishes annually – that he has kept since the 80s. Looking at the sprawling exhibit, it is obvious that anyone trying to count the number of nudes in his 2001 diary, thereby inferring the number of women he has slept with for the year, will inevitably lose count. The only conclusion that can be made is that it was not a bad year, especially for someone who publicly concedes that his sex drive is weaker than most but reckons that his lens has a permanent erection.

Each image of “Last Year 2001” is made with the camera date turned on, hand-printed on photographic paper that is about size 8R.

“I feel that his pictures always have this cinema-like quality, which is why I have stacked them up in rows and columns, much like a mural. Of course, the nature of the gallery with the lack of wall space has made it a challenge for us to set up the exhibition,” elaborates Bridget Tracy Tan, gallery director and curator of NAFA. “The images are divided by months, with a few photos from each month removed from the eventual selection here because they are too graphic.”

Standing afar, the remaining images dissolve into thumbnails, resembling the layout of a pornographic webpage.

“Mr. Araki doesn’t think this is porn, but if you think it is porn, then it may be so,” continues Isshiki. “He is not interested in provocation. Neither is he trying to make a big statement or create a scandal. Moreover he never forces any gallery to show his ‘difficult’ pictures. These are not the main reasons for him to do photography. At the end of the day, he just loves to take pictures.”

The portion of his work exhibited at NAFA, sub-titled “Wanted: Dead and Alive – works by the genius photo-maniac, Nobuyoshi Araki”, features selections from “Untitled 1965”, “Yugawara Stories 1998”, “Banquet 1993” and “Sentimental Journey 1972-1992”.

In many ways, “Sentimental Journey 1972-1992” is quintessential Araki. It is a documentary of his marriage life with his wife Aoki Yoko till the day she lost her fight to ovarian cancer in 1990. The first part of the series sees the couple embarking on marriage life – going to honeymoon and having sex.

“Araki has always said that it is Yoko who made him a photographer. Without Yoko, he will not be able to realize his photography,” Isshiki explains. “You must remember, in the 70s, there were not many Japanese women who wanted to be photographed, let alone being photographed during sex. Just imagine how radical it was for Yoko to allow Araki to make these images.”

As the series proceeds chronologically, across the wall on one side of the gallery, viewers start to see pictures of Yoko being warded and the landscapes that Araki saw when he made his daily trips to the hospital. The series “ends” with her death and a stark snapshot of her grave with flowers in bloom.

On the adjacent wall, a different “mural” of Araki’s pictures – titled “Banquet 1993” – shows close-ups of the food that Yoko used to cook before her death.

“Taking pictures of everyday life that is not normally ‘important’ in the photographic sense of the word is very important for Mr. Araki,” adds Isshiki. According to the manager, Araki has an undying desire to devour life and to murder the concept of time with each of his image.

In her introduction to Araki’s exhibition, Bridget Tracy Tan writes: “To take a photograph is to kill something, to put into celluloid a moment once there and never again, a split second glimpse if you like, into something not known before then, and never to be known afterwards.”

This ethos is also evident with his less provocative series, sub-titled “Flowers by Araki”, exhibited at epSITE.

To be fair, Tensai Araki is not all about women in bondage or Kabukicho sex clubs. However, the photographer has previously conceded that he also finds sexual overtones in decaying flowers, which led to The Guardian’s Adrian Searle suggesting that Araki’s flowers may also be seen as a tribute to death although the series is always saucy and bursting with colours.

Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki

Unfortunately, Nobuyoshi Araki is not present in Singapore for the opening of “Life Like – the World of Nobuyoshi Araki”. Yoshiko Isshiki says that his work on Tokyo is so consummate that he cannot afford to leave the city as it is changing rapidly by the day.

“Moreover, photography is so much a part of him that he feels you can communicate with him through his pictures,” she adds.

Nonetheless, she has graciously facilitated this interview. Some questions – “Do you think you are exploitative to your subjects?” or “What will you say if a viewer finds your images boring because they can be easily downloaded from porn sites on the Internet?” – have been left unanswered by Tensai Araki.

Duchamps challenged the notion of art by exhibiting ready-mades. In a certain way, your intention to capture everyday life objectively and exhibiting them is rather Duchamps-like. Is this your intention? If so, don’t you think this challenge against the notion of art is already dated and old?

Nobuyoshi Araki: Marcel Duchamps is a big swindler!

What are your artistic influences?

NA: I’m influenced by paintings, Uki-yo-e (wood block prints of everyday life in historical Japan) and calligraphy. Specifically, I discovered the beauty of monochrome through calligraphy.

Tokyo is very much an integral part of your photographic life. Having worked on Tokyo broadly as a subject in the last 40 years, how has the city changed? Alternatively, how has the way you view the city changed over the years?

NA: Recently, I had a panoramic view on Shinjuku from Park Hyatt Shinjuku. I found that it was just like after the WWII as there are many empty spaces and construction sites. However, Tokyo in general has been developing in a bad way. There is less and less humanity. Everything has become automated and robotic. We cannot find human feelings or emotions in Tokyo. Nonetheless, I continue to wander and take pictures in this city with my camera and tripod – like Eugene Atget in Paris.

In an interview, you mention that you tie up your models with the real intention of reaching their hearts. What do you mean? How does bondage reveal the psyche of a woman?

NA: All women fall in love with me, become gentle with me.

At NAFA, your images are unframed and stacked up. At your past exhibition at IKON Gallery in Birmingham, your pictures are again spread across adjacent walls, unframed and abutted. Is it your intention to overwhelm the viewer with your images or your photographic world?

NA: Taking a photo is like enclosing the object in the frame of the camera. So if I put my photos in picture frames, they will have double frames, as though they are in coffins. So I should keep them unframed. In this way, it also shows the relation and ambiguity between photography (inside) and the real world (outside).

You sleep with all your models because the photographic experience is very intimate. How do you define intimacy? Is it equivalent to sex and sex only?

NA: During each photographic session, the model(s) and I expose ourselves to each other. We cannot hide anything. Even the feeling or the relation between the two is open. It also applies to the cityscapes that I make. There is always a certain naked relationship between my subjects and me, though I sometimes betray this relation… (laughing)

What is the greatest challenging in photographing nudes? What is the greatest challenge in shooting Tokyo – the city you love?

NA: In general, the most challenging aspect of photography is taking pictures without any prejudice. As I am taking pictures, I am so engrossed that I do not think of anything else – like how to take pictures, which technique I should use etc. The mere act of taking pictures, this is the most exciting thing to me.

Share

Comments 12

Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki http://t.co/o4i8lnBo

Interviewing Master #Araki at InvisiblePhotographerAsia

http://t.co/vrmEUekl

Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki in @InvisPhotogAsia #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/n8lnF3Yn

Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki http://t.co/ww4bhK0S

Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki http://t.co/afFyxpAP

In case you missed it, An Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki. #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/udpHhail

In case you missed it, An Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki. #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/udpHhail

In case you missed it, An Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki. #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/udpHhail

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki ##ipaphotoasia http://t.co/s7pKOFLM

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki ##ipaphotoasia http://t.co/s7pKOFLM

In case you missed it, An Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki. #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/udpHhail

In case you missed it, An Interview with Nobuyoshi Araki. #ipaphotoasia http://t.co/udpHhail