Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable

After spending the early part of his career working at The Straits Times in Singapore, photographer Tay Kay Chin received an offer in 2001 to be the Presentation Editor of The Sun in Bremerton, Washington. While waiting for his visa from February to May, Tay shot Panoramic Singapore using the Hasselblad XPan and a 45mm lens. The series won him international acclaim when he was named a Hasselblad Master in 2003. On www.singlish.org where the series is now hosted, Tay explains that Panoramic Singapore is his “attempt to document a side of Singapore which is vanishing and is seldom presented to the outside world”.

The Singaporean photographer continues: “The truth is, I have never really liked my country. I felt that things were too controlled, and there were not enough opportunities for artists like myself. The truth also is, that I have never tried to understand the whole idea of living in Singapore.”

Although he had initially thought that he would be relocating “for good”, Tay returned to Singapore merely four months into his appointment. Since then, he has worked as a freelance photographer and a lecturer at Nanyang Technological University. Tay’s clients include TIME, Newsweek, Singapore Tourism Board and MTV Asia, amongst others. His photographs have been collected by Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, European House of Photography in Paris and private collectors. He has been on the selection committee of the National Arts Council’s Cultural Medallion and Young Artist awards – the highest accolades for the arts in Singapore – since 2003.

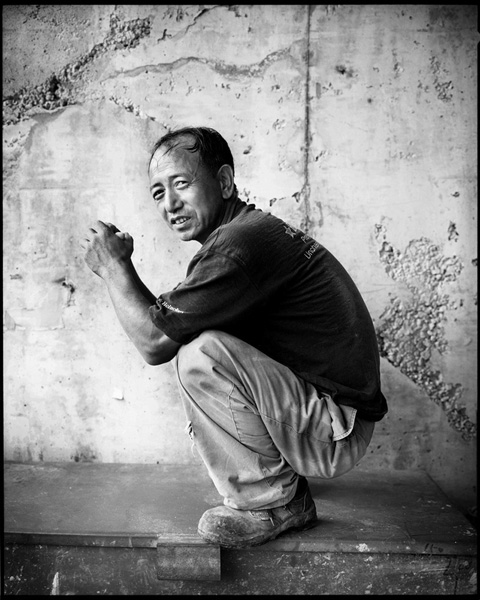

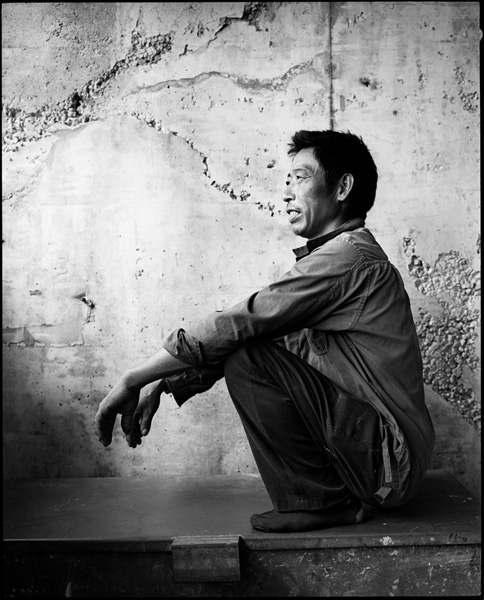

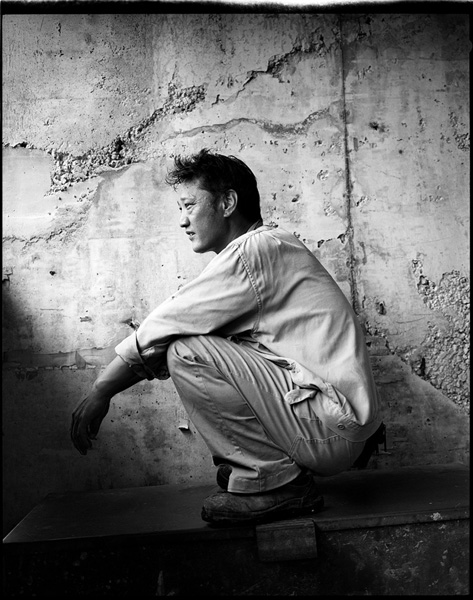

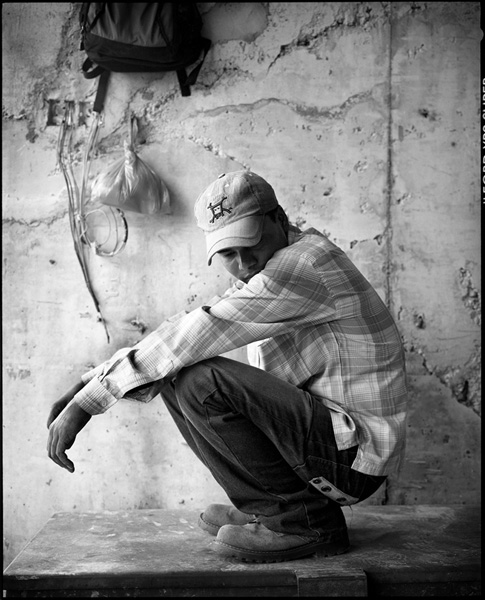

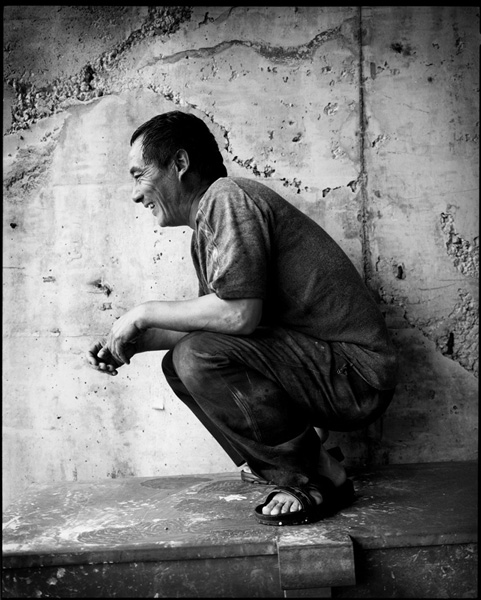

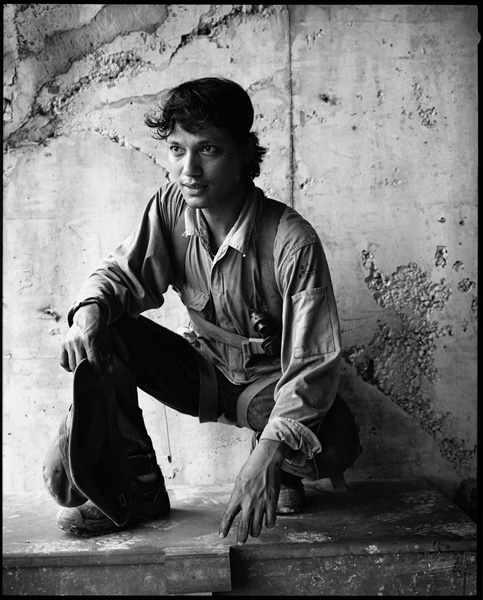

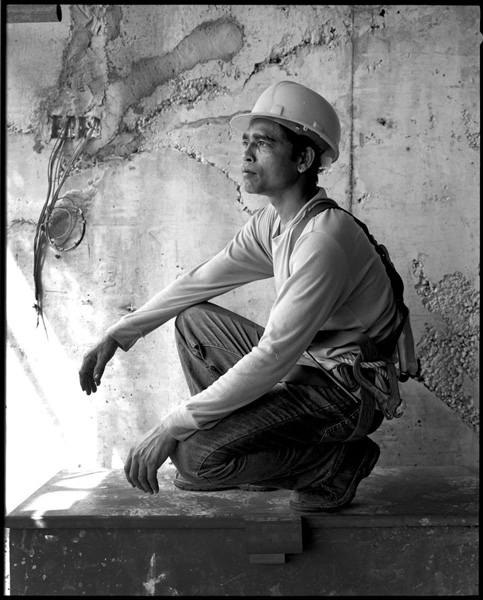

In conjunction with Singapore’s National Day in 2006, Tay Kay Chin exhibited Unphotographable – a new series of images shot over the last five years using Mamiya VII compact 6×7 rangefinder camera – at the Esplanade Tunnel. The series is also available on www.eastpix.com.

Introducing the exhibition, the photographer writes about his burden “to discern what is picturesque and what is unphotographable” in Singapore.

“How do I convince a man that his sunning of pillows along the corridor is worth recording, when he has been doing it for years?” he explains. “There seems to be no immediate answers, only more questions. I shall continue to believe in photography and not words.”

After years of waiting, Tay has finally published Panoramic Singapore in the form of a book. In conjunction with the launch, Zhuang Wubin talks to Tay Kay Chin about his love-hate affair with Singapore and the balance he seeks in maintaining his artistic tendencies against his intention to raise pertinent issues.

Zhuang Wubin: After the success of Panoramic Singapore, what are the motivations that compel you to work on Unphotographable? Are you worried that Unphotographable will be benchmarked against your panoramic series?

Tay Kay Chin: Success is a very big but relative word. I have been told many times that my panoramic pictures are not good at all. If we are measuring success by how Panoramic Singapore is being discussed, then I have done well.

Unphotographable is really a continuation of Panoramic Singapore. The feeling is very much the same – of confusions, of admirations and of protest. My stubbornness has convinced people that I really mean it when I say there is a lot to photograph in Singapore. But Unphotographable is also slightly different. I am still as sarcastic and judgmental but at the same time, I’m more prepared to give Singapore and myself a chance.

Panoramic Singapore got me the Hasselblad Master; Unphotographable has not won me anything, so there will no doubt be comparison. But at this stage, what I care more is saying things that I want to say. Sure, awards and recognitions are important – they often mean money – but I don’t need them to carry on.

ZW: Are your concerns in Panoramic Singapore still pertinent in Unphotographable?

TKC: They are still relevant.

As a Singaporean, I’m not comfortable with the oneness that seems to have taken over our satellite towns. I dislike going to the malls, as I’m unable to tell the difference between Bishan and Chua Chu Kang because all the shops are the same. I am not happy that there are many invisible people that the society seems quite happy to ignore. I am referring mostly to foreign workers and people who are not too well off. We see them everywhere, yet we don’t see them. I believe many of my pictures are deemed unphotographable because they are just not good-looking. I admire the common people – how we can go on with our lives no matter what happens. Most people seem quite capable of shutting out what is bothering them and carry on with their lives.

With regards to Unphotographable, I get a big kick from hearing what people pick as their favourite images. Two pictures always get mentioned – the pillows in Marine Drive and the red stockings. A lot of people like them because they are a part of us. The red plastic bag series within Unphotographable also has a big following. I am conscious that we in the east lack major icons like the ugly arches of McDonalds. I think the red plastic bags in some of my images are more flexible and less obnoxious.

ZW: Your time with The Sun lasted only for four months. Did the stint provide any context to Unphotographable?

TKC: By the time I was ready to go in 2001, Panoramic Singapore was beginning to make a lot of sense that I didn’t want to leave. It was the first time as a photographer that I had found a voice. So it was very hard to leave.

When I came back, it was more because I hated my new job and a horrible side of the USA – it was just after September 11 – that I couldn’t stand. I tried to continue with Panoramic Singapore but my pictures were bad – they were too clean and crafted. They were devoid of emotions and honesty. I was afraid to make the same mistakes that had defined my earlier images and made them successful.

When the original set of Panoramic Singapore came out, the images were all gutsy – bad light, ugly expressions, messy, chaotic. People reacted positively because they saw something they were familiar but had never quite seen in pictures. Most of them loved it and sent me encouraging notes. When I resumed, I felt very pressurized to makes pictures of the same vein, so I went out searching for them. I refused to shoot in many instances because they were not “as perfect”. I ended up with images that were aesthetically more complex but less truthful.

Moreover, the urgency and anguish were no longer there, as I was back to stay.

ZW: While it is debatable if the photojournalistic approach is the best way to generate awareness on different issues, your work is definitely very personalized. Do you think such an approach is counterproductive to your aim of highlighting issues, given that viewers may be lost in the viewing sensation?

TKC: I started out being very concerned about labels but I found them restrictive and meaningless. I don’t think raising social issues can only be done in the photojournalistic way. What is the definition of photojournalism in the first case? I don’t think aesthetics and raising social issues are mutually exclusive. I don’t think my style overpowers the images. Even if it does, I have to accept it.

It is not always bad that a photographer is known for a certain style. In his early works on Haiti, Alex Webb made gory scenes of death look more like beautiful paintings. Photographers have long been influenced by painters like Goya, whose work epitomizes that spirit.

It’s more important that people actually look at my pictures. This is step one. Then, because they see me as someone with a message to say, they will accept what I have to say. It’s a bit like winning awards. Can we say that it is bad? I don’t think so. Winning awards means I have a louder loudspeaker.

The irony is that when one labels himself or herself a documentary photographer with social concerns is one obliged to do anything for the society. If one is an artist, one doesn’t seem to have that burden. But then, who is to say that artists have no social conscience? My own take is to forget the labels.

ZW: It is not a question of labels. There are only a few images in Unphotographable that seem to highlight the issues that you claim to raise. Why is this so?

TKC: Look carefully. They are everywhere. In Unphotographable, there are at least five pictures of foreigners – plus quite a few images of older people, or of people drinking alone. It is the same for Panoramic Singapore. What you don’t see are images of the well-to-do, the establishment.

ZW: But re-examining Unphotographable, there is only an image of Bangladeshi workers in the five pictures on foreigners. The rest seem white-collared.

TKC: If you choose to dissect my images in this manner, there will be no end. I’m not a photojournalist. I am not interested in the methodology used by photojournalists.

I went out on Chinese New Year’s eve looking for like-minded people – people who didn’t have reunion dinner – because for years, I tried to run away from the festival. I have a whole series of pictures of random people sitting alone at bus stops and hawker centres. Not all of them are included in the final edit for Unphotographable.

There is also a sub-series on Marine Drive within Unphotographable. I wanted to look for people living below the line in Singapore’s most expensive housing estate – Marine Parade. I found two blocks of rental flats and many old folks who would while their days along the corridors and void decks. Again, not all the images are included in the final edit.

The project is much larger than what I have shown. There are many sub-groups that I am still working.

When I mention the issues that I am concerned with, I’m not necessarily referring to the images in Unphotographable or Panoramic Singapore. These are issues that I’ve identified with as a photographer.

For your info, I have worked on different projects and many have yet to see the light because I just cannot cope. One of them is a long-term project on the beauty contest for Filipino maids in Singapore.

Truth is not always what I want. Impressions and what the subjects want to portray are equally important. When I worked on the beauty contest, I was troubled whether what they told me was the truth. Then, someone reminded me: “Why are you so obsessed with the truth?”

The truth is that many of the maids live in their fantasy world on Sundays, when they are off from work. For one day in their lives, they become beauty queens. They told me different stories on different days. In the end, I decided to shoot the project like a fantasy.

Lastly, as a writer, you have the liberty to opine on anything. My desire to photograph Singapore is work-in-progress. Perhaps you will have a bigger picture when you see all my projects.

ZW: For photography to bloom in Asia, everyone has a role to play, including the critics. I’m not one though. What I’m trying to do is to put difficult questions across to photographers and provide them with the space to respond.

TKC: Yes, you have asked questions that I wished others had asked, because as a photographer, being heard is important. However, I can’t say the same when I am misconstrued.

There are many issues I am unpleased but they don’t necessarily translate into photographs or projects. For example, I have been very anti-American government since my return in September 2001, but I have not found a way to deal with it in my work. I have also stopped eating sharks fin for many years but I can’t see myself doing a project on environmentalism because photographically, it is not my persuasion.

I’m worried I will be judged against what I am not. Being a photographer doesn’t mean everything I do revolve around photography. At times this is a burden. I once read an interview on Sebastião Salgado, who was asked what he felt about sending his kids to private school when he had obviously made his wealth from shooting the poor. His answer was quite simply this: One shouldn’t feel ashamed to be rich.

I’m concerned when people associate me with photojournalism when I’m nowhere near being one myself. I have many social concerns, but I don’t love chasing the news as a photographer. I am a news junkie who reads newspapers and watches BBC everyday, but I have no desire to be at the frontlines making pictures.

Lastly, I should say that my photography has mainly been personal. I make pictures just to please myself, not to change the world or the society. However, I hope people will respect my perspective. This is the basic right of a photographer – the right to possess an individual voice.

ZW: Having shot Panoramic Singapore and Unphotographable with two very different cameras, do you think they have offered you different views of Singapore?

TKC: Not really, but the change from 35mm to medium-format has given me new energy. Nowadays, when I try to frame with the panoramic camera, things just don’t fall in place naturally. The XPan is motor-driven, so it is easy to keep shooting. Changing film is also easy. The 6×7 is the exact opposite. It is cumbersome and slow. When I shoot with the 6×7, I am more patient, waiting for moments. I also shoot a lot less as loading and reloading is more tedious. So subconsciously, I slow down. It is a really good change. Now, I’m even thinking of using a large-format camera.

ZW: The exhibition of Unphotographable is timed as a gift for this year’s National Day in Singapore. How will you describe this gift?

TKC: It has always been my hope that the powers-to-be take a wider view of what our country is about and what we ordinary people feel. I don’t think the tourism board people like me very much but I’m very sure if some white men had shot the same images, they would have paid big money for them. In other words, people whom my “gift” is intended may not accept them. To be frank, I don’t really care. If people talk about my work, I am already satisfied. If the series inspires more photographers to question the meaning of being a Singaporean, I will be happy.

Share

Comments 10

Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable. http://t.co/nrDpZy3r

Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable http://t.co/5AkkS3yL

Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable http://t.co/sItd7PsA

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable http://t.co/qM1D50AK

RT @InvisPhotogAsia: Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable http://t.co/qM1D50AK

For photography to bloom every1 has role including critics. As photographer being heard is important. http://t.co/AjlQhMkc –@InvisPhotogAsia

For photography to bloom every1 has role including critics. As photographer being heard is important. http://t.co/AjlQhMkc –@InvisPhotogAsia

For photography to bloom every1 has role including critics. As photographer being heard is important. http://t.co/AjlQhMkc –@InvisPhotogAsia

For photography to bloom every1 has role including critics. As photographer being heard is important. http://t.co/AjlQhMkc –@InvisPhotogAsia

Tay Kay Chin’s Unphotographable

http://t.co/jP4PfiFz