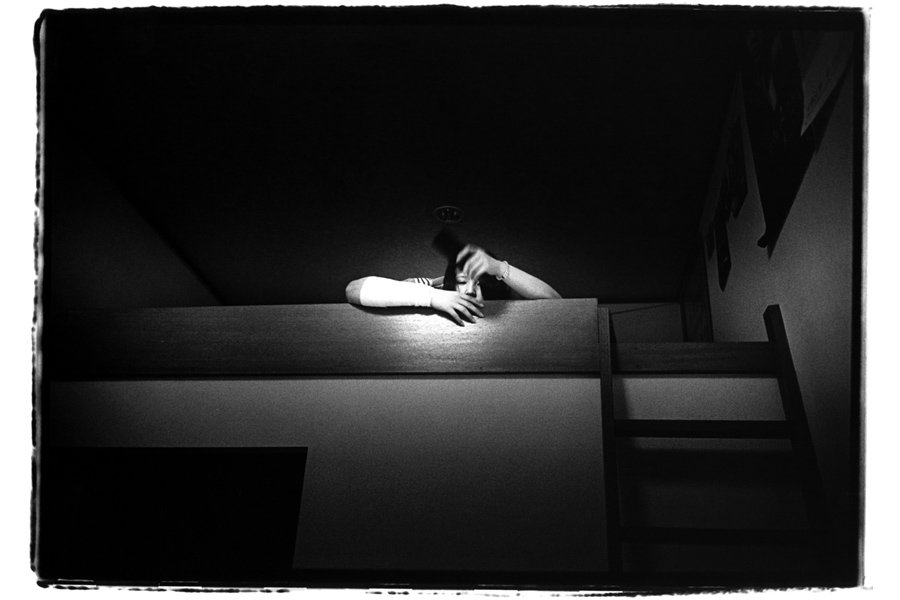

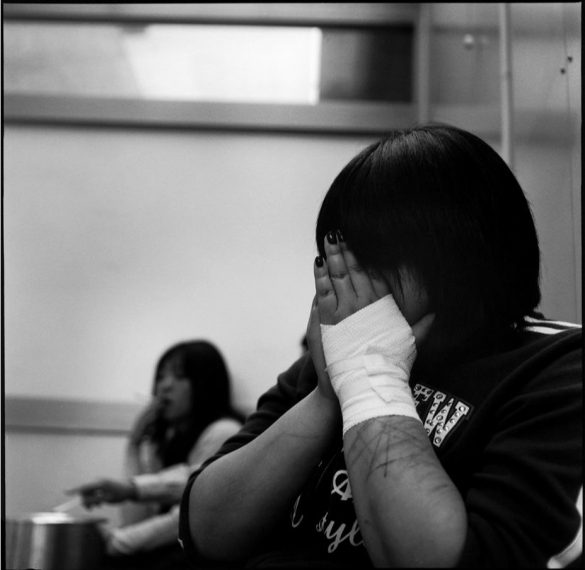

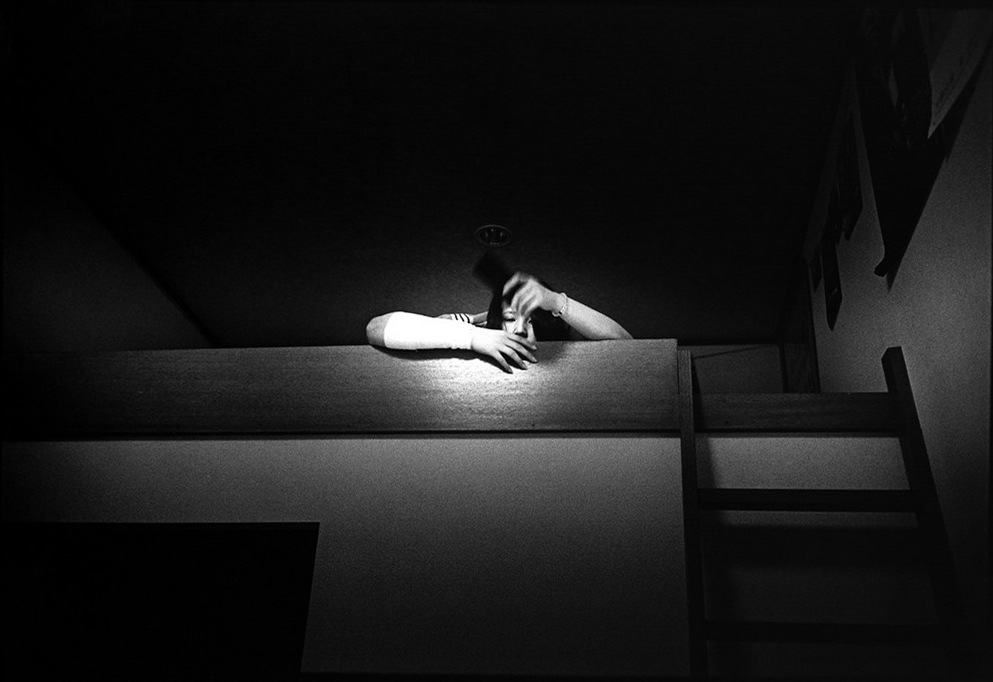

Kaori, 23 years old, relaxes in her room. She rolls bandage to stop bleeding after she cut her arm. IBASYO, © Kosuke Okahara

1: A Photographer Comes Full Circle

‘Ibasyo’ is roughly defined as the physical and emotional place where a person can exist, a location or a state of mind, where a person feels comfortable or at peace.

In December 2014, I was at the Angkor Photo Festival. It was my first time, and I was surprised at how warm and welcoming the atmosphere was. It was a small community of photographers, and I was one of the few writers among them. Every day I found myself engaged in conversations about new work, the state of photography in Asia, and the world. One of the people I got to know there was Kosuke Okahara, a Japanese photographer. As we shared lunch, at the end of a long week, I saw a box lying next to him.

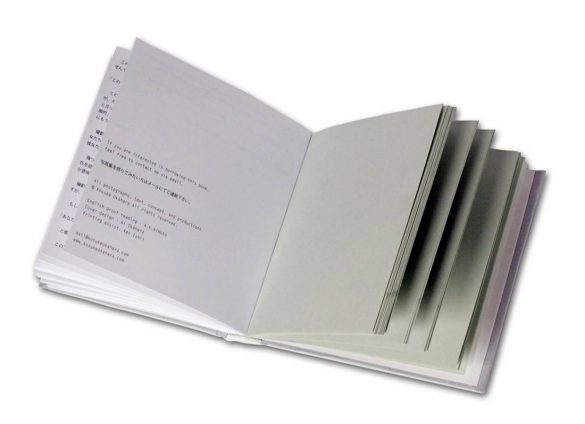

I opened the box, inside was a small book covered in grey linen, the word IBASYO embossed lightly into the covering cloth. The opening text revealed that this book contained the story of six Japanese girls Okahara had photographed who cut themselves, an act called self-harming or self-injury.

The images were moving, as was the text. Okahara had written about his experience of being in the room when Yuka was cutting herself, “It was a strange moment for me… to take pictures of it. I wondered whether this was the right thing to do. It was the only way, however, I found to accompany her. Most of the people who cut themselves have traumatic experiences that denied their existence. I tried to recognize everything they did”.

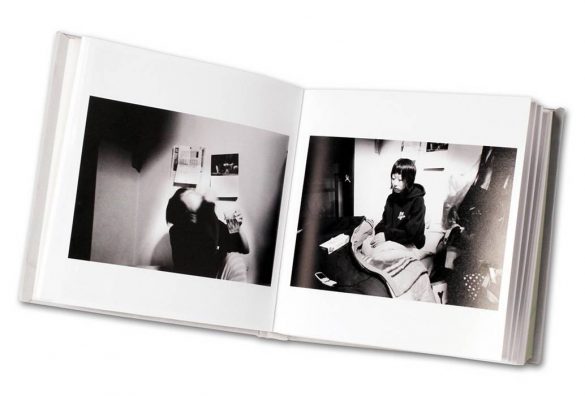

Each image was about this recognition of existence. Simply being present. A few pages in, I found myself thinking that this was a book worth owning, something I could return to.

But in the closing essay, I learned that I could not own this book. No one could. It was one of six, handmade by Okahara, each one named after the girls he had photographed — Yuka, Kaori, Hiromi, Miri, Aina and Sayuri — and they were the ultimate owners of these books. All I could do, was write in it, write to them, write my response to their story. Half the book had been left empty for this purpose, and the first few blank pages had already been filled.

As I began to think about what I wanted to say to these women — to Sayuri whom I had seen sitting on the floor of her bedroom, expressionless, wrists ripped deep, to Kaori who had overdosed on pills and had to be taken to the hospital, to Miri who had emailed Kosuke and said, “I feel I can try to change myself” — I looked at the images again, and again.

Hiromi — Her scarred hand reaches out into a void. There is no one standing there but as the light falls on the edge of her wrist, you sense that she is trying to reach out, maybe to herself. Aina — You see her clearly in her room, the bodily form framed against the light of the computer screen. You think you see a form on the bed as well. There is no body there, but you can imagine someone hiding under the sheet, crumpled, softly crushed. And then you see her in a public space, she’s a guitarist. She is standing head bowed against a wall, playing. A man walks past her, a blur, and suddenly she seems to have become a backdrop, an unnoticed presence on the street.

I read the text more closely. I thought about what “self-harm” meant in my life. Had I ever felt this type of despair? Even though I didn’t cut myself, didn’t I find ways to harm myself when I was younger and lacked confidence in who I was? And these women, who had agreed to reveal the most intimate part of their lives for the world to see, what did I think of them? Were they brave? Were they weak? Now that I had the opportunity to let them know that I had seen what they experienced, what would be the right thing to say?

The tissues that Akane wiped her blood after cutting herself. IBASYO, © Kosuke Okahara

I wrote a single page. It was difficult.

As I capped my pen and closed the book, I realized I had just become part of something quite unique, part of a chain of contact that Okahara was preserving for these women. When I googled “Ibasyo Kosuke Okahara”, I learned that anyone, in any country can request access to the books and Okahara is coordinating it such that they circulate from one to the next. As the books travel, Okahara maintains a blog tracking each of their journeys, using Facebook to connect the book-journey with a wider audience and allowing individuals to request access to the book through a dedicated website. On his blog, Okahara writes:

‘All of the girls I photographed told me that they want to see themselves through someone else’s eyes. It can help them reevaluate themselves. Before they told me that, I could not have imagined that the pictures I took might be of any help… if the girls know that other people out there in the world care about them and their stories, then maybe this could be a small step for them to re-develop their self-esteem. In a way, this might sound a little patronizing, but I want the girls to feel that they are important.’

The more I thought about this the more I realized the beauty of what Okahara had accomplished. Even though the images themselves had already been widely seen in the last few years, published in magazines and exhibited at photo festivals and galleries, he had given the work fresh meaning and life through this “Book-Journey Project”.

As Stephen Mayes, a veteran of the photo industry, has said, “Photographers are no longer constrained as humble suppliers to platforms managed and controlled by others; thinking as publishers allows them to choose their themes, audiences and the means of expression and distribution. How we grasp the opportunities before us becomes partly a matter of problem solving and, more significantly, a challenge of imagination”.

IBASYO Photobook by Kosuke Okahara

And Okahara had taken this challenge head on. By removing these 6 “photobooks”, for lack of a better term, from the economy of the art world, by not allowing their circulation in museums or galleries but instead taking them to ordinary individuals each with their own experience, their own perspective, each looking at the story in their own solitary space, Okahara had given the viewer, the reader, the recipient, a sense of agency and ownership over the work.

A decade after he first began photographing, Okahara has come full circle with this story. He has found a way to bring the world to the women who let him bring their stories to the world. And he continues to shoot. Even after the work has seen commercial success, and is now traveling in the form of these books, he hasn’t stopped taking pictures of the women. Some are better, some aren’t, some may be soon, some may take turn for the worse. He is still there.

2: The process leading to the creation of “Ibasyo”.

As I wrote in part one of my discussion about Ibasyo, I was both moved and inspired by Okahara’s dedication to the girls and the form of distribution he is using — from person to person. He agreed to spend an hour with me speaking about the decade long journey that lead to this “experiment”. Here is the full text of our conversation (with minor edits for clarity and flow):

Alisha Sett: When did you start the project?

And how did the idea come to you?

I met a girl who had a habit to cut herself. We started talking and became friends. And she said — it’s in my book title — she doesn’t feel “Ibasyo”. Ibasyo means emotional, or even physical, space where you feel you can exist. It could be social status, maybe house, it could be nice family.

She said she cannot feel this “Ibasyo” and that’s what I also felt when I was kid. So I felt kind of close… I saw the scars.

I started some research. At that time I was looking for a project in Japan, I wanted to do something in my country but wasn’t many interesting things. I felt like it has to be a good reason to do a project for me.

Portrait, Kosuke Okahara

Is the concept of “Ibasyo” something talked about quite commonly in Japan?

Yes. Not really everyday because if you’re happy with what you’re doing and who you are then you don’t feel the need to talk about it.

But many people who is… excluded… or don’t feel really right in what they’re doing… How to explain… It’s difficult to explain.

Maybe describe your “Ibasyo” as a child.

My father was an alcoholic so it was quite violent family. I felt like maybe I should not exist… I shouldn’t have been born or something.

How did you break out of that?

I grew up, and became bigger and stronger. And my father became weaker as he ages, and he stop doing this kind of habit. (Laughs)

So that changed the equation.

Also, when I finished school, I started photography. I was doing some part time job in the school I was studying.

And then what people told me is, “Hey! Don’t do something stupid. Just get some job. You’ve never done photography, why you’re saying you’re going to be a photographer?”

I took some pictures. It was not good. So they said, “You’re not talented. Don’t do this”.

Some of my friends came to see me who were studying at the school, (they said) “Hey — what’re you doing? You just graduated. You didn’t get any job?” This kind of thing…

Especially in Japanese society, you feel lots of pressure when you’re not doing well, when you don’t find what you want to do. I found what I want to do but…. people think I’m just following my dream… they felt it doesn’t make sense.

So yes… that kind of feeling. (Laughs again)

Once you started your research, you found an online community where you could find people for your project?

Its called Mixi. It’s like Facebook in Japanese. I posted that I want to do this project and if anyone interested… or if anyone can help me out. And I explained what I wanted to do and my aim.

What did you say was your aim?

I wrote about why I want to do this. And how I want to do this.

IBASYO, © Kosuke Okahara

What was the how and the why?

The why was the meeting my friend and what we talked about, and wanting to do something in my country, and I felt this was a very deep issue in Japan. Which is still hidden. Not too hidden, but individual level it’s kind of hidden. They don’t want to talk much…openly. It’s very sensitive.

Also, I wrote that this is documentary so if possible I want to spend as much time as possible. I said I want to stay in the room. I want to, kind of, live with them. And I said I don’t want to hide anything. I don’t want to put some black thing on their eyes to hide their face.

For me, photography is the kind of process to recognize people I photograph so if I do this (black out portions of people’s faces or bodies) it’s very opposite… then I deny the existence. Photography… when you’re covering the face — what do you see? You make them as taboo. I feel like it’s just not right.

So I wrote this kind of thing and also put my phone number, email. Then people started calling me or emailing me. Some people misunderstood… (they ask) how much you pay? Is it a model thing? Some people understood and were quite okay.

First one came to me after few weeks. I went to see her and then talk to her and then started shooting. She said, “Yeah, you can stay at my house”. (I said) Thank you. That’s how I started.

Was it difficult to establish these relationships?

No secret. Some people are just open enough, you just meet and immediately they’re okay. Sometimes, you need to take time. Sometimes, it doesn’t work out. There’s no real secret to get access.

I explain (the project) well. For this case, I also talk about maybe the bad effect it might have. Because I want to publish, I want to have exhibition, I want to have maybe book. I explained I try to protect as much as I can, but there might be some unthoughtful criticism that make them feel bad. At the end I didn’t receive any negative comments on them though.

I told them I don’t disagree if people say I’m exploiting…. Whatever… It’s true I’m going to make money out of this. I don’t think I can make more money then I spend but I said that it’s also true when I publish, which means I sell, I get money. So I wanted to let them know the facts even if my intention was telling the story. Simply, I didn’t want to hide anything.

I met twenty… maybe thirty people.

What was it about self-harming that made you think this is a good project?

I shot people who self-harm but it’s not actually about self-harm I think… its about how they… how one can actually recognize one’s self. How one can actually see herself or himself as important.

What I found while shooting this story is that self-injury is basically not… of course cutting is a problem but… the most important thing I found was how it’s important to have self-esteem.

I felt like they don’t have self-esteem… they couldn’t develop self-esteem. So one said, “I don’t know how to love myself. People say you have to take care of yourself but I don’t know how”. Because she had some experience that really denied her so she feels very guilty being in this world.

IBASYO, © Kosuke Okahara

How did you help them process these thoughts?

I talked about myself as well and while I’m shooting we shared many things. I talked about my father, I talked about my life and then they talked about their life. So in a way it was very intimate but of course we are not talking all the time like this. We became like friends so we talk about stupid things as well.

So was your personal experience, of thinking about self-harming in your own childhood, essential here?

There are many great photographers out there who never experience what the people who they shoot (do) but they took great pictures and communicate very well.

Whereas I have similar kind of experience but the picture (could) really sucks!

It depends. Some people do great work without personal experience. For me, it’s okay to have experience but the dangerous thing now is that… Let’s say a person has some difficult experience and then he/she is shooting pictures of people who have same experiences. It sounds very legitimate but you cannot use your experience as an excuse to shoot somebody. It’s a different people. Even if you have similar experience it’s not exactly the same. How you feel is not exactly the same so at the end you just end up using your experience as an excuse to shoot pictures. At the end, I feel your just using… you’re just using them to do what you want… by using your experience.

I don’t think it’s important. It’s also too easy. If you say I’ve had a similar type of experience, okay, but then you don’t think enough…

For me, whatever I do is very connected. The subject I choose, and the way I photograph. I can’t explain… whatever I shoot it’s very related to this title ‘Ibasyo’. The way I photograph… my pictures are kind of simple, its not very complicated.

I really want to try to capture the existence in the picture. When people look at the picture, I want them to feel that they actually exist here, that its not only paper.

Tangible existence?

‘Ibasyo’ means how you can actually exist. You need somebody to recognize you to exist.

Lets say if you come here (to the Angkor Festival) and then no one talks to you, you feel so excluded right? You come here and people welcome you, they get to know your face, name and they treat you well. You feel like you can be here. I think that feeling is very important for everybody.

And do you think photography can do that better than most mediums? Create this sense of existence?

I don’t know. Could be. But not every photo can do. You never know.

You say in the book that ‘I could not have imagined that the pictures I took could be of any help’, but it seems that this project in the form of these traveling handmade books, has found a way to be of some help. What was the process of deciding that this would be the form for the project? How long did it take to have this realization?

I wanted to publish this. I was about to publish (a book) but finally the publisher said no. I was thinking about how I could get published… then I applied for this book prize in Europe. If you win they publish your book in five languages. I was a finalist but I didn’t win.

Then I was saving some money to publish this book… but I was also thinking if just publishing book is right to tell the story? Okay, publishing books, distributing it… yes, you can tell the story but there are many books out there. Just publishing, publishing, publishing… that’s fine because that’s the fundamental way to communicate but the same time I was feeling it’s not really enough. There’s something missing.

Of course telling a story is what they (i.e., the girls) also wanted based on what we discussed but I felt who is going to take advantage of the book? First it has to be them.

I was not really feeling comfortable just to publish, even by myself. Then, maybe last year around January I was thinking what to do. And of course when I started shooting, they said they want to see the pictures. They want to see themselves from the outside. To understand, to look at themselves to understand what they’re doing. So every time I published in magazines, I was sending the magazines to the girls and they were quite happy.

I knew they need to look at pictures, they want to. So when I published a book, of course I was going to give them.

At the same time, I talked to people. I was also at that time interested in doing something new. I was kind of bored…

Now, everyone says that the financial situation is going down. That we have to find another way to do things. Then I wonder… we always talk about money and money is important to carry on the project, and then we talk about crowd-funding. And it’s important thing. I paid for some of my friends projects but then I wonder who finances the projects… I guess it’s basically people like me who is in the same industry… then the question is if we can bring the story to the people who are not in the photo industry… of course this is my challenge too.

So far, I have quite a few people who have nothing to do with photography who showed their interest, and I am happy about it.

If you had published this as a traditional book, it would have sold well. Probably most books you will create now will sell well. Does that make you feel unless you create out-of-the-box forms like ‘Ibasyo’, it will become quite easy for you and your work to just become another product? I guess any photographer who sees success has to struggle with that question…

I don’t know about others. But for me I couldn’t find a good reason to do just (a) book. And this work… because of my previous book, I knew I could sell quite well. This work has been around for quite a long time… many years people know this work. It’s not actually new at all.

This work in particular I got lots of email from people I don’t know. They talked about the issue. But I couldn’t find a good reason to publish it so that’s why I didn’t… I couldn’t first but then I didn’t.

At the same time, I was interested in this flow of information using internet and communicating. But I felt that if you put those images on the flow of information because flow is so fast, it becomes like news pictures — you publish and the next day it’s old. Why I have to put these photographs on the flow of information which makes the pictures go so fast?

So picture has to be not on the information but I can use the information… to spread information. That was the idea.

I also wanted to do something for the girls. And it has to be tangible. I can just get comments by email or whatever but it’s not right… it’s not tangible.

Why is the tangible element so important for you?

Because when you receive a physical letter versus an email you feel very different.

How long do you think this journey will take for the books to travel back to the girls in Japan?

I don’t know, but it is taking more time than I expected. So probably in 2–3 years.

When the book was traveling in Europe, some art students borrowed (the book). And they did something very nice, they draw something with a message, it’s very beautiful.

Where did the idea for keeping the half the book for writing come from?

I thought that if the girls can see the trace of people, it’ll be good. If it’s just borrowing the book, you don’t see much, but if they write something it really shows they recognize the girls.

But also I had this worry… not really worry… If you write first, you know people are going to read what you write so I feel that people some people more honest, some people less honest because they’re shy. Or maybe they feel kind of obligation… I have to write something nice. Even if the person doesn’t really feel this way. Maybe that happens. But it’s interesting to me because it’s actually how society is made.

When the book goes to the girls, I have to translate because some of them don’t speak English. For them, it’s important because they have hearts which are made of glass. When they stress in their normal life they cut themselves. I am hoping they also see how the world is constructed, how the society is constructed. So far it seems people are very helpful, and giving something very honest and touching. I said that something negative might happen too but at the end, it seems they will find the world is full of care.

The book becomes a small reflection of society for them.

That’s what I’m hoping. It’s nice that it’s organic.

You wrote in the book that keeping people informed is important for you and that you always want to see what you can do for the people you photograph. Is this a concern for all your projects?

I don’t really know. Photography cannot really do something to the people. Maybe at the end it comes back to people. Maybe… but it doesn’t happen most of the time.

The kind of photography I do is shooting some particular subject. So I don’t think it helps much.

You have to think about it (with every project). You know you can’t do much but it’s important to think about the subject first.

When did you realize what it took to communicate well? Or recognize that simplicity of style is something you wanted to maintain?

Maybe after 2007 when I went to shoot this leprosy village in China.

I have a friend who was a volunteer in one of the villages. He kept asking me, “Lets go, lets shoot story”. But I couldn’t find good reason to shoot story. The reason why those ex-leprosy patients are discriminated, kicked out their house or home, is basically the appearance. So what’s the reason to photograph those people? To show their appearance is not good?

After a few times we discussed, my friend started telling me, “Disease is actually going to finish… going to end. Now, medicine is available. And every year less and less patients”. Most of the patients are old and they’re going to die anyway. He said, “Maybe the disease will be gone in 20 years or 30 years but then maybe how they actually lived, the history of those people, it might actually end or diminish”. He said he doesn’t know if it’s the right thing to lose history of those people. Disease be gone — is good — but the history might also be gone.

So suddenly you had a reason.

Yes. I felt for that reason I can photograph.

But when I went I wasn’t sure how I can photograph… If I shoot appearance it’s going to be bad, its going to create another discrimination. So I was thinking how can I shoot this.

So then I thought the most important thing is that people recognize that they are here. That’s important. If they can feel that they can exist here, that’s important.

And you give a sense of beauty throughout the book. As you enter the place, through the images, you don’t think about disease. You almost get the sense that you’re entering a haven.

I just focus on capturing the existence in the picture. Which I don’t actually know… or see when I’m clicking. I focus when I’m shooting… not on a concrete idea… I don’t know how but… trying to capture the existence of the people.

And of course, I can’t see it! When you’re clicking, you don’t see it. It’s just your idea or what you’re trying to do.

There are not much moments you know. People are just there. They don’t move much. They are quite old (i.e., the community of elders living in the leprosy villages).

I don’t know how I capture, but I always want to try and capture the existence. Maybe I use the elements I see in the frame to capture the existence. Maybe I just use all those elements to make it work as I shoot existence but… I don’t know how.

Thank you Kosuke.

Request access to Ibasyo here. And see more of Okahara’s work here.

Text and Interview by Alisha Sett. More from Alisha: https://medium.com/@alishasett

Share

Comments 1

Alisha, this was soul-stirring, raw and eye-opening. It was a powerful read, and such a potent insight into something so fundamental as the recognition of one’s existence.