Bird Hunting with Tele-Pinhole Camera, Excursion #5, 2015 © Lam Pok Yin Jeff and Chong Ng

Contemplating on the rapid transition of photography in the last two decades, a surge of young contemporary photographers have been creating work centered around analogue photographic process and alternative photography. Jeff Lam is one of them and he can tell you why this wave of retrospection is not just some nostalgia-driven obsession.

The Hong Kong photographer originally trained in architecture challenges mainstream norms and provoke viewers to investigate the relationship between photographic process and images. In his series, ‘The Untimely Apparatus of Two Amateur Photographers’, he and his classmates, Chong Ng, turned seemingly unrelated objects into cameras, creating images that cannot be otherwise produced by your everyday click-and-shoot camera. In this way, Jeff and Chong wanted to subvert the popular assumption that camera is a delicate and expensive equipment.

The project also reveals that the conventional equipment that we have grown so familiar with image making, a tool, according to Lam, can put up an illusion of free photographic choice and limit the possibility of “what light can create when it hits a photosensitive surface”. The series won the Portfolio prize of GuatePhoto 2015 Open Call from over 1,700 entries. So when the now Shanghai-based photographer came back to Hong Kong in late October, I caught him for an interview. (The conversation is edited for clarity)

What is your history with photography? What is your first camera? How did you become a photographer?

JEFF LAM (JL): When I was around eight, I found a pentax camera with a zoom lens. I liked to use it as a telescope to look around. Eventually, I developed an interest in photographic equipments. Then at around a similar time, my family got a Kodak instamatic camera for buying electrical appliances. It was one with no manual control, no flash, just a press-and-shoot camera. I played with it a lot. One time I thought of adding a camera flash to it, so I just tied a flashlight on the camera. That is my first experience modifying a camera.

After graduating from The University of Hong Kong with an architecture degree, I worked in an architectural firm for an year but I felt that what I did was not improving our living environment. I worked on some project in China, spending countless night hours working on a colossal architecture in the middle of nowhere, obviously built to boost up the city’s GDP. More often, architecture has nothing to do with design but politics. I was dissatisfied with what I was doing, so I decided to take three years off to pursue another career, working as a freelance photographer and designer. That year, I applied to a photography school.

The Untimely Apparatus, 2015 © Lam Pok Yin Jeff and Chong Ng

How is your research process for your award winning project at the Guate Photo Open Call – The Untimely Apparatus Of Two Amateur Photographers?

JL: One day, My partner Ng received his work from his printer in a 1.5-metre giant mailing tube. We got this random idea of making a pinhole camera out of it, the biggest telephoto pinhole camera ever. We were curious about the photograph this ultra-tele pinhole camera would produce. We put a photo paper at one end, did some basic light proofing and took it to the backyard to try it out. We kept refining the apparatus and experimenting with different pinhole sizes.

At the time, bird watching was pretty popular among hipsters in the UK, so we had this idea of going bird watching with this camera as an satirical and playful comment on the new trend of equipment fetish. We found out the the exposure time was too long for photo paper so we switched it to negative and built a 4 by 5 film chamber. We bought a hunting rifle scope as a viewfinder – a suggestion from Ng who had been in military service. The finished product was a ridiculously mammoth camera. It became the first piece of our project.

We brought it with us to a wetland park in suburban London, as well as two binoculars. We set up everything, posed and took self portraits of ourselves using the self-made camera. It attracted much attention from visitors.

The initial idea is to make a camera out of objects that somehow related to its function. After the telescope, we have brainstormed a list of cameras we wanted to construct and worked on some feasible ones. The entire project is about camera itself, its structure and properties.

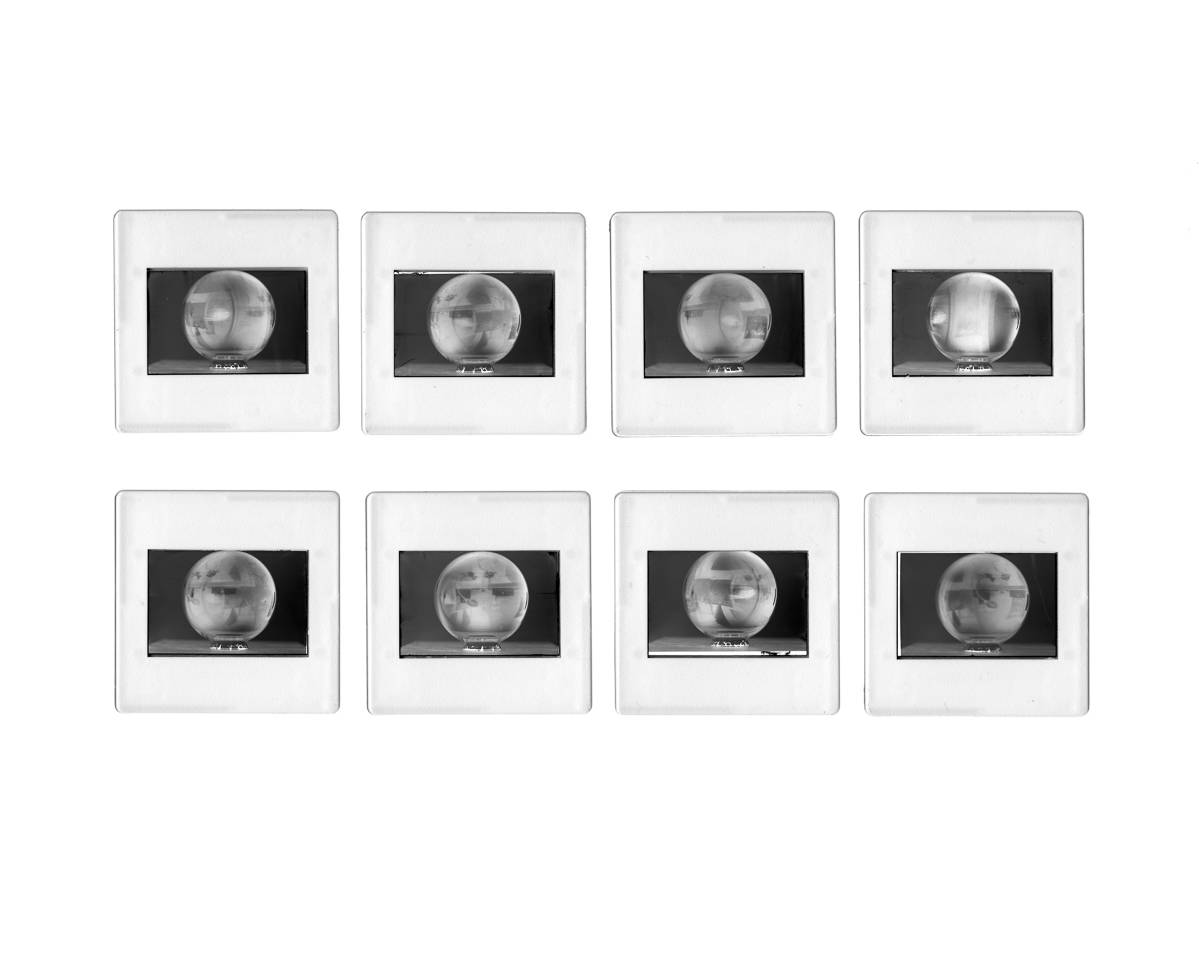

We started working on our second camera, using revolving projector, after seeing one in Saatchi gallery. Being machine maniacs, we thought of inverting its mechanism and revert the light path so that the machine absorbs light into its body instead of projecting light. The second camera is about how photographic technology compresses 3-dimensional reality into 2D imageries. Inspired by the circular slide holders, we created a light sensitive sculpture, exposed with a camera with multiple lenses to make a 3D negative. The sculpture is then photographed again with the projector-camera 360 degree and convert the 3D negative into many comprehensible 2D positive slides.

Demostration of Modified Ektapro 9020 Cine photographing Glass Sphere Negative, #17, 2015 © Lam Pok Yin Jeff and Chong Ng

For the third camera, we wanted to work with a bigger and more abstract concept. We worked with pinpoint of a reality for the tele-pinhole camera, three-dimensionality for the projector, for the third one, we decided to experiment with time. Originally, we thought of placing photo paper on a analog clock to do a long-exposure light painting of some sort, but we later had an idea of using a flip clock. It makes much more sense. Each flip could be a new exposure and each flat plastic indicates the exposure time. The flip clock we used, as we found out later on, was produced by Copal, a Japanese large format lens manufacturer and has been making flip clock for decades. For mechanical nerds like us, the discovery further supported the idea that time and photography have an intricate and subtle relationship.

The execution was exceptionally technical. Some clock has 1 flat plastic for each minute (00 – 59) while some have one for digit in one and in ten respectively. We used the later one with fewer flat plastics as we need more space in the back of the clock to expose photo paper. We expose the paper for 9 hours. The result is a photograph with four different exposures of the same scene. The exposure time of each part is the same, yet depending on lighting environment, the resulting image is different. There have been many trails and errors.

In your statement statement you said that new photographic technologies while democratising the art of photography, can also be a restriction to new narratives. What do you mean by that?

JL: No doubt, this project is a critical approach to contemporary photography. The digitalisation makes photography truly democratic. Everyone have a camera in their pockets these days. Anyone can afford what used to be an aristocratic luxury in the past. Photography is much less expensive yet this also means we have fewer possibilities when it comes to taking a picture. If we understand photography as simply “traces of light on a light-sensitive medium”, then making an image by clicking a shutter would be abandoning many other alternative techniques such as len-less photography and photogram.

Media scholar Vilem Flusser inspired this project. A camera is just a black box. He said If we stop questioning the development of this image-producing black box, soon photography and camera mechanisms would be predominantly controlled by marketing decisions. The image you get will be limited to what these cameras can produce.

And that has an broad effect to not just photographers but the society as a whole. We understand the world through images. If the cameras on the market all tend to create for example, close-up photos, we may slowly develop preference towards a certain kind of familiar images. People may think they are shooting freely and making conscious choices, but the moment you pick up a mainstream camera on the market, the choices you can make is already limited by the machine.

Chinese and Japanese traditionally spend a lot of time talking about composition. There are countless discussions on the photographic image, focusing on literally the surface of the photograph, the visual elements, the thing you see. Photographers spend a lot of effort recreating a certain visual style and relatively little on the photographic process and its significance. Thus, this project is an antithesis of the indifference to the relationship between imagery and photographic process.

I am curious about the title of the project? Why do you emphasise on ‘two amateur photographers’? Is it a conscious choice to separate yourself from the mainstream professional photography in order to establish an outsider critical perspective?

JL: Yes. I instinctively wanted to challenge the prevailing notion that professionalism means the creation of smooth and glamorous images. I think commercial image is too perfect and too easy to digest. You can say I put the word ‘amateur’ in the title as my stubborn refusal to that ideal.

The way we produce this project is also very amateurish. It all started from playing with a mailing tube. We finished much of our experiments at home. We did not have a professional darkroom, but a laundry room where we developed photos, built our camera and conducted every testing in. We learnt everything from scratch. We went on Youtube for tutorials if we got stuck. We asked around for answers. The things that we had been doing fits into the idea of amateur.

We did all that out of curiosity. The project is a prove that one need not to be a “professional”. Yes, you need to understand the basic mechanism of a camera and how it contributes to the construction of images, but photography does not have to be high-tech. Camera is not a refined nor delicate equipment as marketers wanted us to believe. It is something that anyone could temper, build and modify.

Glass Sphere Negative, #17, Re-photographed by Modified Ektapro 9020 Cine, 2015 © Lam Pok Yin Jeff and Chong Ng

How does your education in architecture affect your approach to photography?

My training emphasises on a critical thinking process. Every design element has to be supported and justified. Every step of the research process has to be interlinked. and thus coherently bringing out your ideas. No decision is arbitrary. We don’t do things just because we like it a certain way. At the time, I really hated the methodology, but it turns out to be very useful to think about photography.

What is your working relationship with Chong Ng? Why do you choose to work as a duo? How does it all happen?

JL: We are classmates. We became friends in the first year of school and then moved on to live together with other photography students in the next year. We have always shared many common interests, especially in machinery. We would share links about things like installations and machines that smoke cigarettes. We had similar vision aesthetically. In the third year, I decided to team up with him for the school’s group projects.

The collaboration was really smooth. Because we have similar expectations for the outcome, so we save a lot of time arguing or communicating despite that we have different approaches. When we brainstorm, we did research online together. We conceived some possible experimental cameras. We shared our sketches. We will then keep some of these rough ideas our head, waiting for it to evolve and mature.

I cannot finish this project by myself. There are too many technical matters to deal with on the operational side of the project. Countless trails and errors. For instance, to take a photos with the flip clock, we have to disassemble the clock, make sure the flat plastics are in the correct sequence, cut and paste the photo paper to the exact size and reassemble it again. All these done in our makeshift darkroom for 3-4 hours in pitch black. There were too much frustration for one to bear. Each of us is responsible for a particular role, He spent more time with execution while I am responsible for presenting and articulating our concepts.

Who inspires your photography?

JL: Steven Pippin comes to my mind. He is a prolific artist in the 80s who works mainly on performance-based art related to photography. He once turned a photo booth into a giant pinhole camera and posed for his self portrait outside of it. For ‘Homage to Muybridge’, he made photos using a row of washing machines by simply putting a photo paper in the right moment and pouring developer inside. The resulting image is a series of consecutive photographs of him walking overlapped with dark blobs and scratches caused by the movement of the machines. He is someone I truly respect and has huge influence in my work.

Other contemporary photographers that inspire my work are duos like Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin and Tay Onorato & Nico Krebs.

Interview by Sheung Yiu originally published on urbanautica.com.

More Photographs © Lam Pok Yin Jeff and Chong Ng

~

Share