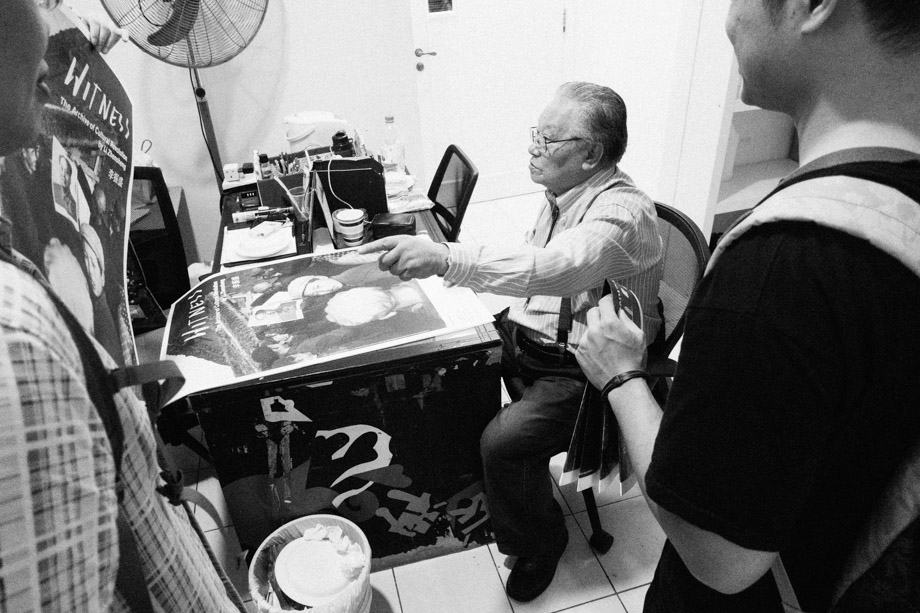

Li Zhensheng at the guided tour of his ‘Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution Exhibition’. Photograph by Sebastian Song.

Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution focuses on the socio-political upheaval in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976, recorded through the unflinching lenses of Li Zhensheng 李振盛, then a photojournalist of the Heilongjiang Daily.

The exhibition showcases, for the first time in Southeast Asia, over 100 images illuminating insights into the tumultuous event, interspersed with intimate documentations of Li’s life as a young Chinese grappling with times of great flux and uncertainty.

The exhibition opened at The Arts House on 9 September, the 40th death anniversary of Mao Zedong. A day later, Li conducted a candid and informative tour of his exhibition to some thirty participants. The following are highlights from the tour.

“During the Cultural Revolution, only positive aspects would be published and featured. Anything negative was not permitted. Images depicting struggle sessions, dunce caps, destruction of property and places of worship are seen as smearing black, i.e., denouncement of the Cultural Revolution. As a photojournalist, I understood that both good and bad are co-existing and complementary. Unfortunately exhibitions in China even today focuses only on the good.” – Li Zhensheng

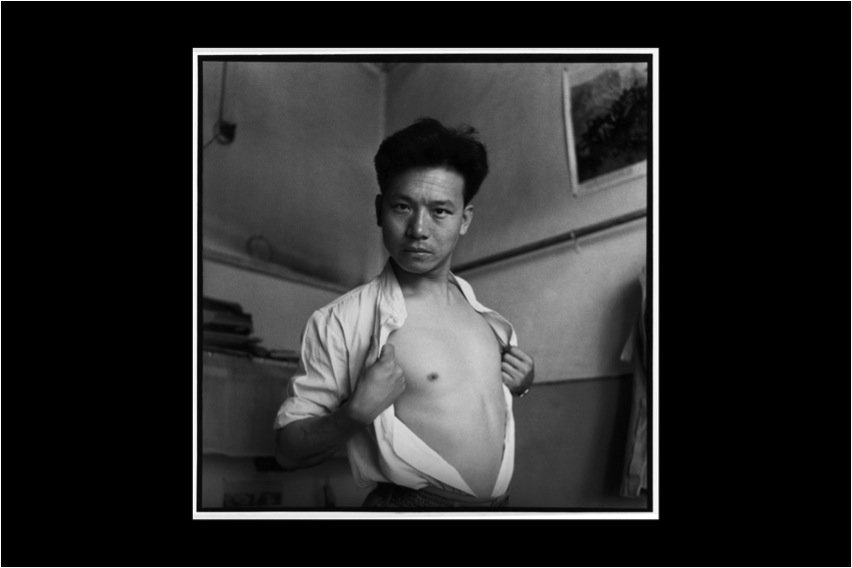

“The usual practice for my exhibitions is to use this as the first image. Robert Pledge, the editor of my book, Red-Color News Soldier, and many of my exhibitions, wanted all visitors to be “greeted” by me when they enter.” Li Zhensheng. Photograph by Sebastian Song.

“The usual practice for my exhibitions is to use this as the first image. Robert Pledge, the editor of my book, Red-Color News Soldier, and many of my exhibitions, wanted all visitors to be “greeted” by me when they enter. In all my self portraits, I always looked at the camera. If you are photographing someone, always ask your subjects to look at the camera. This is to ensure that your subject will always be looking at you, the photographer. If you ask your subject to look anywhere but at the camera, an inevitable glance into space will be captured.”

© Li Zhensheng, SIPF 2016

“I was a film student at Changchun Film School. However, the school was closed during the Great Famine. I was naturally upset as I was unable to fulfil my dreams of becoming a film director.

When I was a photojournalist at the Heilongjiang Daily, I had the practice of saving the last negative after my assignment. This was to safeguard against any emergencies, usually traffic accidents, that might arise on my way back to the press. Often the last negative remained unexposed. Instead of developing the last unused negative, I used it for my self-portraits. Self portraits allowed me to exercise my creativity. More importantly, I was able to embrace all four key roles in film-making, i.e., script writer, director, cinematographer and actor.

When we were shortlisting the images for Red-Color News Soldier, Pledge saw the image and exclaimed, “I discovered a classic self portrait!” My daugher, who was then my translator, was equally excited until she saw the image. She questioned why I took such a photograph and called my wife to complain. My wife was equally puzzled and asked her what’s wrong. She replied softly that I flashed my nipple.

I tried to pacify my daughter, explaining that in Beijing, the male street peddlars are often topless. I have only flashed one and not both nipples. She remained unmoved, insisting that the image be excluded from the book. Pledge, believing that this image will impress many, took the next three months to persuade me and the rest is history.”

© Li Zhensheng, SIPF 2016

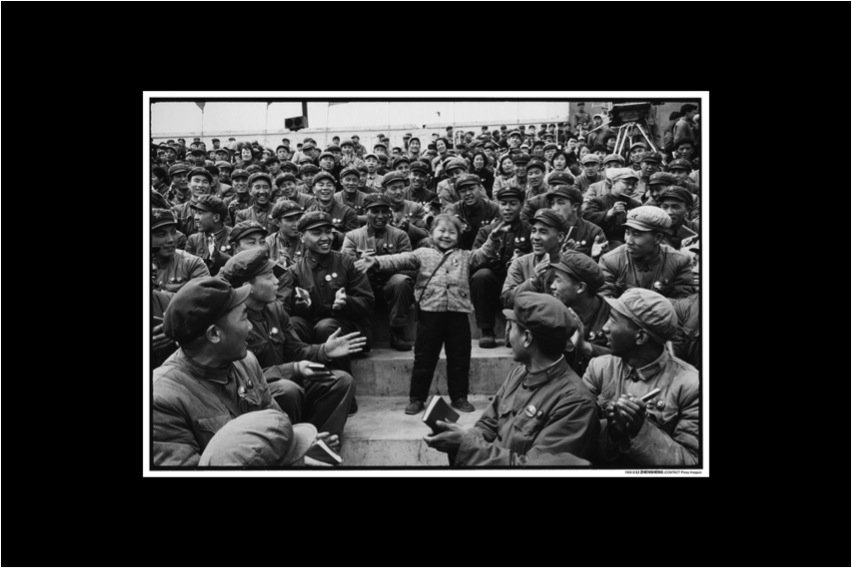

“Kang Wenjie was five. She could sing and perform the “loyalty dance” very well and was nominated as the provincial representative during the Conference on Learning and Applying Mao Zedong Thought. There was, however, one problem. She was illiterate.

It was absurd that someone who couldn’t even read could even understand Mao’s writings, much more apply his teachings. Sadly, such Conferences are often competitions, with provinces contesting to see who has the youngest and oldest participants. Every province strived to showcase their unique participants. Unfortunately, like the Emperor’s New Clothes, no one dared to speak the obvious truth.”

© Li Zhensheng, SIPF 2016

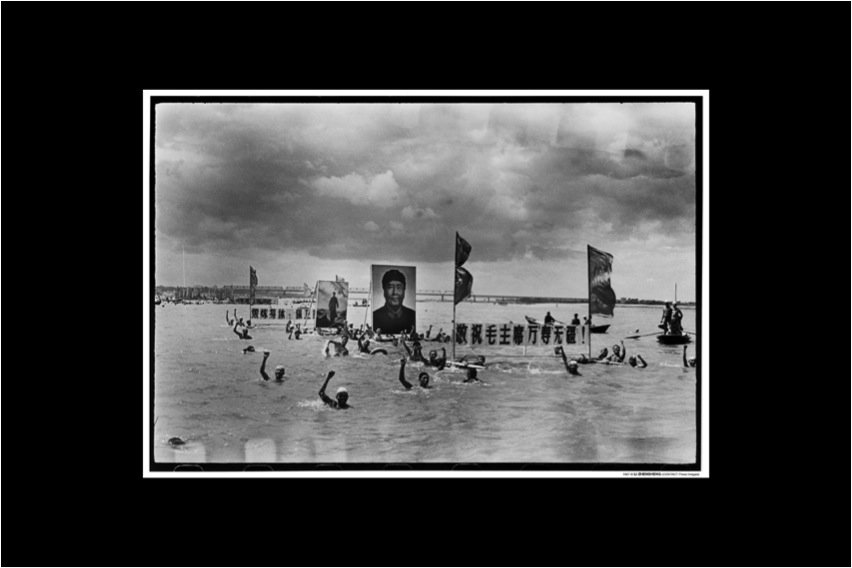

On 16 July, 1966 Mao Zedong swam in the Yangtze River. Every anniversary saw different parts of the country commemorating the swim with their mini swim events. These events were highly politicized. The portraits of Mao were easily the height of several men. The slogan, wishing eternal longevity to Chairman Mao, must be shouted in union constantly during the swim. The task was to shout all nine Chinese characters loudly and audibly.

Those who swim will understand that such gestures are very demanding even for the most proficient swimmer. As I photographed from a small boat nearby, I noticed some swimmers started swallowing water after the sixth character. They were rescued and taken to shore. That is when their trouble began. They were deemed non-believers and counter-revolutionaries and must conduct self reflection and reprimand sessions. Every of my images has a story. This, without a doubt, is an absurd tale during an absurd time.”

Li Zhensheng signing his exhibition posters at The Arts House, Singapore. Photograph by Kevin WY Lee.

~o~o~

I spoke to some visitiors and asked for their views on the exhibition.

“Knowing the context of the pictures made it so much more enjoyable. It also revealed the injustice and bravery of the affected. To think that all these happened within my lifetime is quite unbelievable.” – Teng Kiat

“Witness is a very apt title for the show. To have the courage to present the photographic evidence of an inconvenient history is the very essence of social documentary.” – Edwin Khoo

“The exhibition gave me insight to the bright and dark side of the cultural relvolution. Mr Li shared with us personal stories of the photos, and gave us context of his past and the times he lived in.” – Zu Wee

“Mr Li’s work is not only a witness of history but also a witness of his courage, burden and responsibility. As a Chinese, I hope eventually all Chinese can appreciate our history and the courage to face it.” – Donna Chiu

“Li’s black-and-white and often panoramic format keep harking me to the thundering sounds that must have defined the scenes. Li is such a fantastic story-teller especially poignant in Mandarin; as a listener, one laughs and cries but most of all, marvels at his craft, his courage and his foresight in saving a phenomenal treasure trove of recorded images. Li has gifted to photography precious insights beyond measure.” – Li Li Chung

Thank you to the team at Singapore International Photography Festival for bringing this wonderful exhibition to Singapore.

Text by Sebastian Song. Read More: Li Zhensheng 李振盛: Photography, Life & Vows during the Cultural Revolution.

Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution is at The Arts House, 1 Old Parliament Lane.

Opening hours are 11am to 8pm (Tuesday to Sunday), closed on Monday and public holiday.

Admission is free.

The exhibition will end on Oct 29.

Share