On 9th September 2016, the 40th death anniversary of Mao Zedong, Kevin WY Lee and I sat down with Li Zhensheng 李振盛 to talk about the Cultural Revolution, life, vows and photography.

About Li Zhensheng 李振盛

Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution focuses on the socio-political upheaval in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966 to 1976, recorded through the unflinching lenses of Li Zhensheng, then a photojournalist of the Heilongjiang Daily. Led by the conviction that the truth must be revealed to the masses in order for history not to repeat itself, the intrepid photographer risked his life hiding away negatives that offered an unabashed account of China’s political situation under the rule of Mao Zedong.

The exhibition showcases, for the first time in Southeast Asia, over 100 images illuminating insights into the tumultuous event, interspersed with intimate documentations of Li’s life as a young Chinese grappling with times of great flux and uncertainty. Li has also published a book, Red-Color News Soldier, which focuses on the revolutionary ideals and many of the atrocities that occurred during the Cultural Revolution.

Note: To facilitate the flow of the interview, we provide more background information in the footnotes. Readers are encouraged to read them for greater insight. Additional reading too in Highlights from Li Zhensheng’s Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution.

The First Camera

Invisible Photographer Asia: We read [1] that you traded 200 stamps for your first camera. In a time of great scarcity, why settle for a camera?

Li: I longed for a camera but never thought I could own one. I started collecting stamps in primary school. Every Sunday I would bring my collection to the Post Office to trade with fellow collectors. One day, I met a middle-aged man who wanted to kick-start his collection and offered to swap a camera or a watch. The Japanese made 6×4.5 camera which costs 38 yuan and he combed my collection to find stamps to match the value.

I really wanted both the camera and the watch but I lacked the resources and had to settle for one. I settled for the camera. The lack of film, however, was a reality [2]. Fortunately, my peers knew I was good with photography. Depending on their financial situation, two to ten of them would pool funds to buy a roll of film for me. The camera allows 16 shots which they requested for self or group portraits.

The Last Negative

Li: Having film is like a solider having bullets – you can’t fire at will, but need to aim carefully. I always made sure there was proper lighting and composition. I practiced and honed my skills through the process. In return, they allowed me to keep the last frame in the negatives. This last negative frame I treasured.

What did you capture with the last negative frame?

People and landscape. I focused my creativity on this last negative.

You have great affinity with the last negative. From the earlier episode to your days as a photojournalist at the Heilongjiang Daily [3] where you made it a point to save the last one or two negative frame after every assignment. The later evolved into the self-portrait series. When did you start taking self-portraiture?

I started during my secondary school. Robert Pledge is currently editing my forthcoming book on my self-portraits and panoramic images. My panoramic images were hand-made from two to five images. These days, technology has allowed handphones to create panoramic images effortlessly.

As a film student, self-portraitures allowed you the opportunity to become a script writer, a director, a cinematographer and an actor. Did you have a master script to serve as a reference or were the images spontaneous?

Definitely spontaneous. My practice was to save the last one or two negatives in case of emergencies or unforeseen circumstances.

Is saving the last negative a norm among your colleagues?

No, they usually finish their roll. If they have a few unexposed negatives, they will either develop the whole roll or save it for the next day. In my situation, I would take self-portraits. I’d rather be prepared than panic should the unforeseen occurs. Like a soldier saving the last bullet.

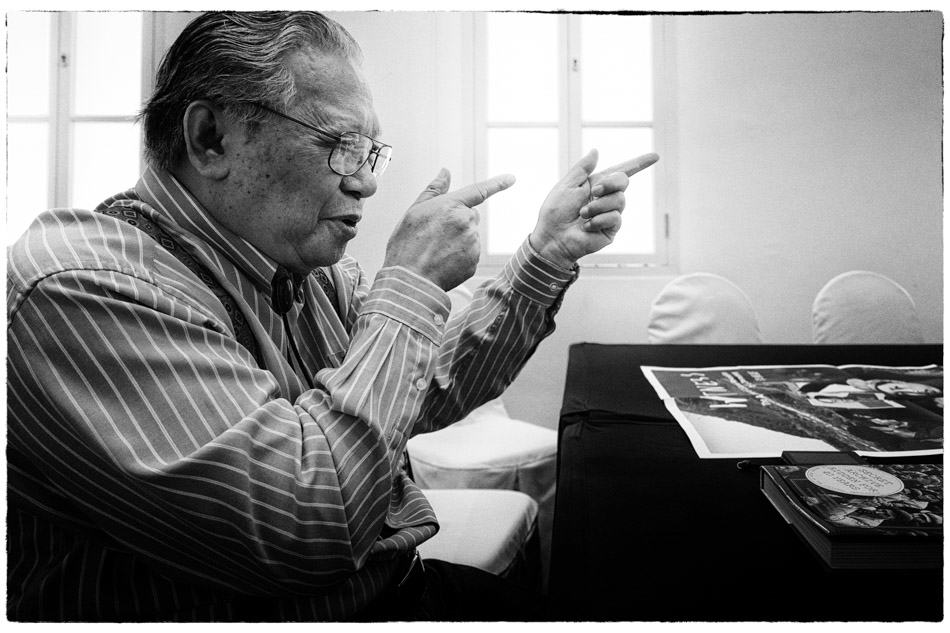

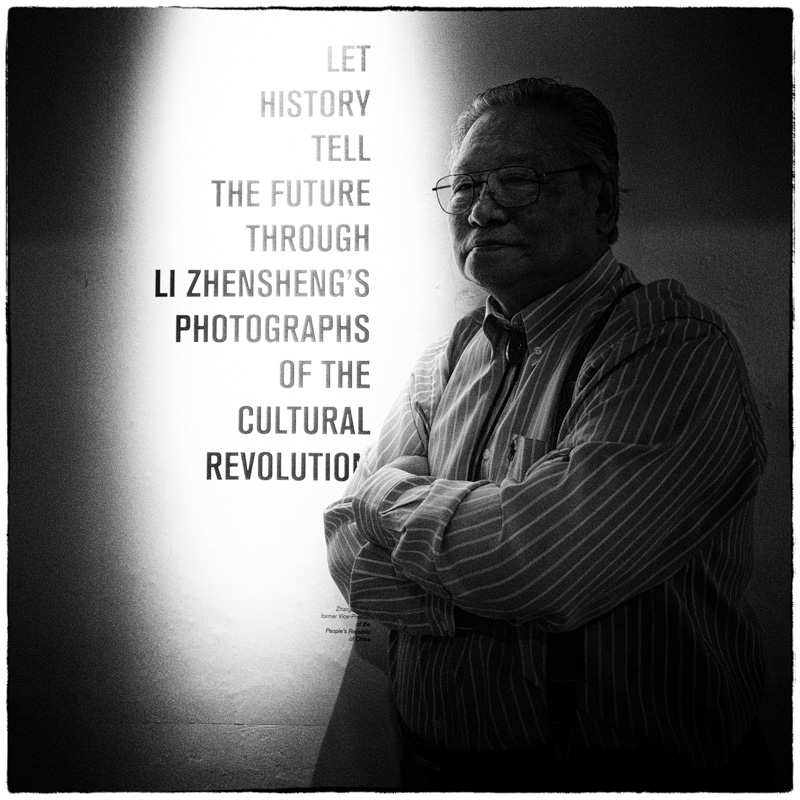

“I’d rather be prepared than panic should the unforeseen occurs. Like a soldier saving the last bullet.” Li Zhensheng Portrait by Kevin WY Lee.

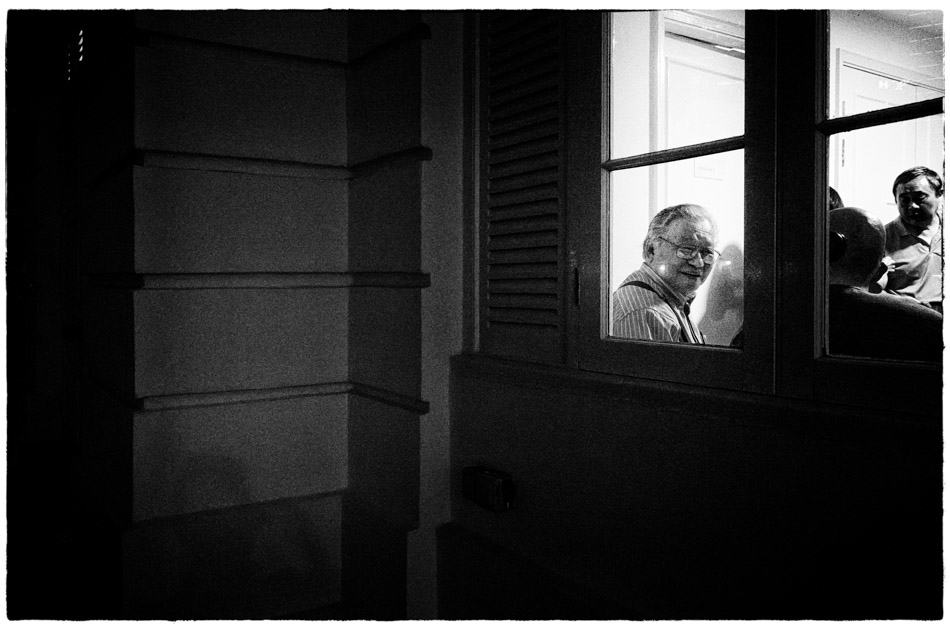

“One evening in August 1963, I made two vows: I will not toil my life away in Heilongjiang and I will travel the world, even if I do not learn English… My wish to travel the world was viewed as being treachous and disloyal.” Li Zhensheng at The Arts House, Singapore. Photograph by Kevin WY Lee.

You would make a good soldier.

I’m not one, but I am serious in whatever I do.

Working at Heilongjiang Daily

With regards to film rationing, we read that you get an extra roll whenever four images are published.

Yes, one roll of 135mm, 36 exposures or 2 rolls of 120mm, 24 exposures.

You must be rewarded quite frequently.

Yes, I was formally trained. Let’s be frank, there’s a difference between going to film school and learning the craft as a protégé. During those days, most are the latter. Photojournalism is like a second career for former athletes or soldiers. In fact, professionally trained photographers are close to non-existent [4].

The Black Borders

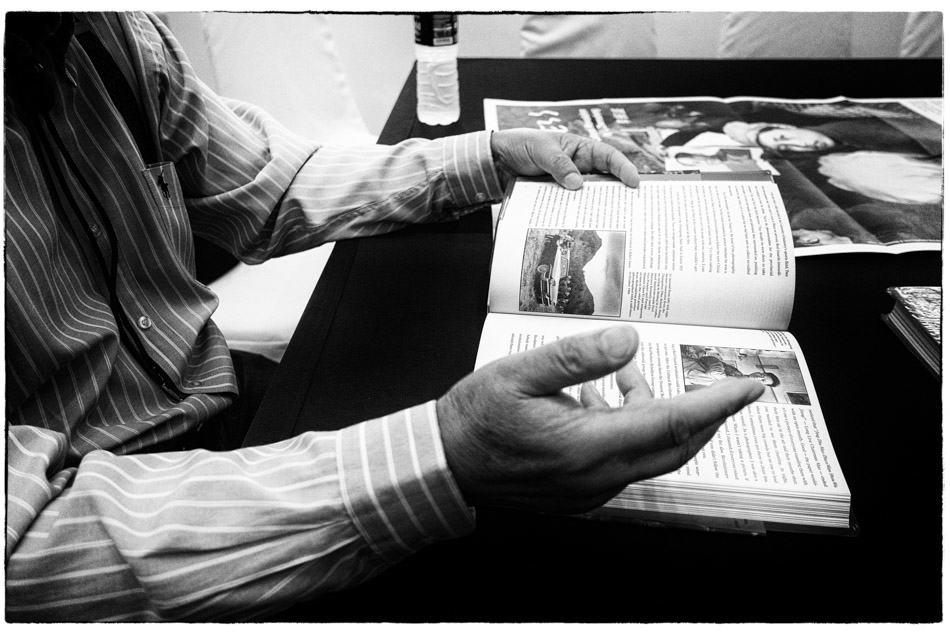

“Every image in my book has a black border i.e., the edge of the negative. When Robert Pledge was editing my book, he wanted the readers to view the photos exactly how I witnessed it. There must not be any doubt that the images were cropped. Many photographers shy from showing their negatives because they like to crop. I always believe a good photographer completes his composition when he presses the shutter.”

Hundreds of thousands in front of the North Plaza Center carry self-made Mao Zedong portraits in a show of loyalty to the “Great Teacher, Great Leader, Great Commander in Chief and Great Helmsman”; Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, June 21, 1968

Modern montage panoramic image is made of three individual images overlapped

Editing Red-Color News Soldier

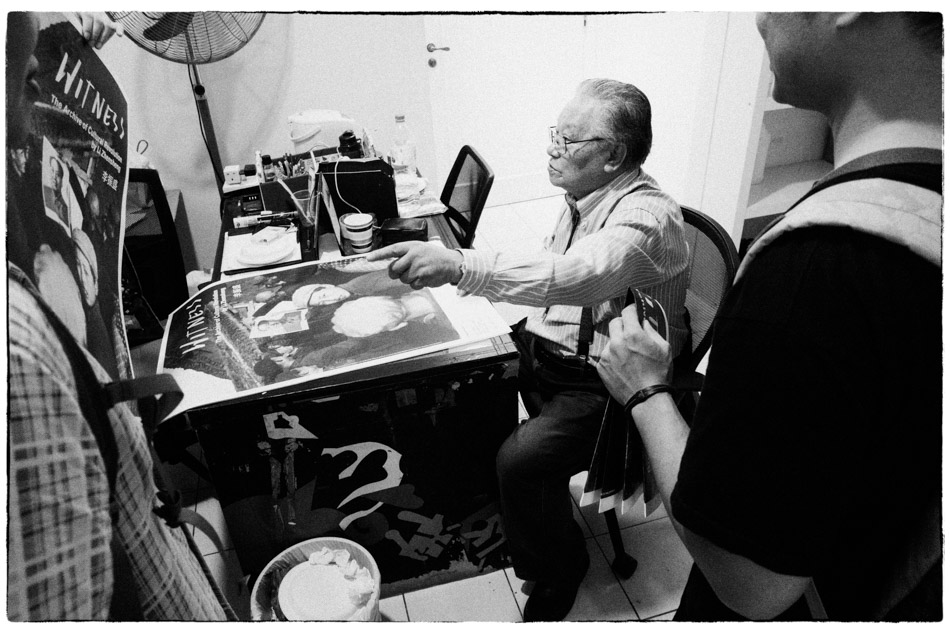

“Starting with 30,000 images, we went through the entire library at least five times. It was tortuous, to say the least. In China, it normally takes two to three months to publish a book. Six months is unusual and one year is considered a major project. We took three years!”

Li Zhensheng on Editing Red Color New Soldier. Photograph by Kevin WY Lee.

The Vows

“One evening in August 1963, soon after I started work in Heilongjiang Daily, I made two vows and wrote in my diary, “I will not toil my life away in Heilongjiang and I will travel the world, even if I do not learn English. [5]”

I was young, angry and wanted to vent my frustration. However, the vows were made with no timeline. The vows resurfaced during my criticism session in 26th December, 1968. I was repeatedly reprimanded and asked why I was special and can’t die in Heilongjiang. I was forbidden to speak. My wish to travel the world was viewed as being treachous and disloyal.

Ironically, the criticism session fixed a deadline for my vows. I was told I have twenty years to leave Heilongjiang and thirty to travel the world. Thankfully, through sheer hardwork and Heaven’s blessing, I fulfilled both vows well within three decades.”

Being a Photojournalist

“My teacher, Wu Yinxian, told me once that to be a photojournalist is not only to be a witness to history, but to record history. It is more important to be the latter. All who lived through those times are witnesses, but what evidence do they leave behind for future generations? Gao Xingjian, winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize for Literature, wrote his life experiences in China, but he was criticized in China for taking liberties with history. My photographs have never been questioned.

My job is not to spend the day determining whether a particular event is meaningful. It is rather, to record the many fragments of history and leave it for future generations to judge. Any human tragedy that occur anywhere on Earth should become an informative archive for all mankind. We must not repeat errors from the past.”

On Patriotism

“I am a patriot. I love my country China. I still hold a China passport. I can be an American citizen and enjoy many benefits but I refuse to do so. The minute I become an American, the Chinese media will gladly introduce me as an American. Imagine the irony of an American who photographed 100,000 images of the Cultural Revolution. Weird, isn’t it?

I still recall ex-Premier Zhu Rongji’s remarks when asked about Gao’s winning the Nobel Prize [6].

I believe I am safe. I am 76 and will continue to remain safe. I hope I will soon be able to exhibit and share my experiences of the Cultural Revolution in the very land it happened, China. My greatest wish is to inform the youths of China of the lives we had.”

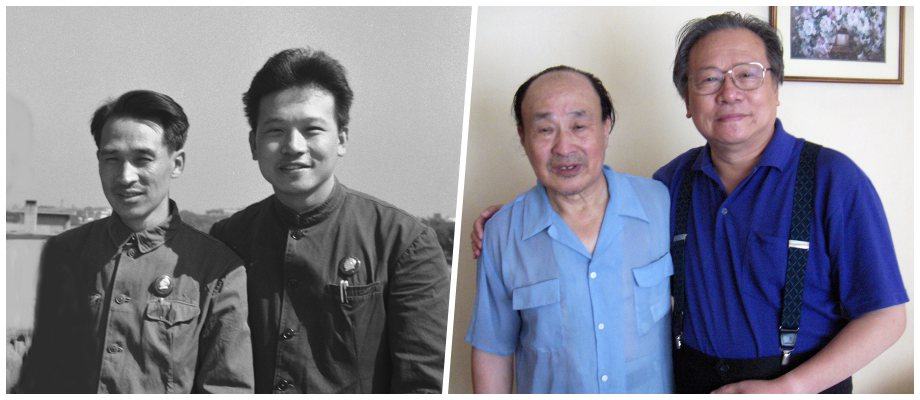

Portraits taken in 1968 (L) and 2006 (R) of Li Zhensheng with Li Mingda, who faithfully kept his secret about the hidden negatives.

A Good Man

On 6th September, 1969, Li and his wife were sent to the Liuhe May 7th Cadre School for rectification. He was worried that they would not survive the labor camp and also about the eventual fate of the 20,000 negatives he had hidden. He had to entrust the location of the negatives to somone. That person was Li Mingda.

The couple invited Mingda to their aparment and revealed the negatives that were hidden in the floorboard. The following conversation took place.

Li Mingda: What are these?

Li Zhensheng: These are the negatives that casts a negative light on the Cultural Revolution.

Li Mingda: Why do you keep such negatives?

Li Zhensheng: They are useful?

Li Mingda: What use?

Li Zhensheng: I can’t explain but they will definitely be useful.

In a time of moral relativism when betrayals took place daily, and among the closest of relationships, Li Mingda kept his silence for 37 years. As we admire and learn from this amazing archive, we should never forget its silent guardian.

~o~o~o~

Footnotes

[1] Red Color News Soldier (RCNS) by Li Zhensheng was published in six languages in 2003. Though out of print, it is still available at selected bookstores or libraries. Please refer to RCNS, pages 22 and 23. [2] A roll of film costs one yuan, one eighth of his monthly living allowance. [3] The Heilongjiang Daily was the largest newspaper in the province, with a circulation of about 2700,000 in 1957. [4] Changchun film school closed before it ever saw its first batch of graduates. [5] Li was originally selected by Xinhua News Agency to go to Beijing and study English at a foreign institute. However he was seen as “disobedient” and eventually replaced. For the full story, please read RCNS, pages 25-26. [6] “(I) believe that there will be Chinese works winning Nobel Prizes again in the future. Although it’s a pity that the winner this time is a French citizen instead of a Chinese citizen, I still would like to send my congratulations both to the winner and the French Department of Culture,” Zhu Rongji answered. Gao Xingjian was granted French citizenship in 1998.

~o~o~o~

Text by Sebastian Song. Read more in Highlights from Li Zhensheng’s Witness: The Archive of Cultural Revolution at Singapore International Photography Festival 2016.

WITNESS: THE ARCHIVE OF CULTURAL REVOLUTION IS AT THE ARTS HOUSE, 1 OLD PARLIAMENT LANE.

OPENING HOURS ARE 11AM TO 8PM (TUESDAY TO SUNDAY), CLOSED ON MONDAY AND PUBLIC HOLIDAY.

ADMISSION IS FREE.

THE EXHIBITION WILL END ON OCT 29.

Share

Comments 2

Hi, I’m trying to figure out where the picture of Governor Li Fanwu was taken. I’m thinking of the picture where he got his hair cut of in Harbin September 12, 1966.

Author

Hi Jogvan, Mr Li was the then governor of Heilongjiang province and the photographer Li was also based there so it should have taken place within Heilongjiang province.