My name is Reinfredo Enrique Celis, village chairman of village 31 of Tacloban City. On November 7, 2013, the City Disaster Coordinating Council warned all residents in all villages to evacuate, because of the expected arrival of Typhoon Yolanda with the estimated strength of 270 kilometres per hour.

At three in the afternoon, I started moving my residents out. At three in the morning, the rain and the wind was too strong. I immediately woke up my wife Celia, my son, and my grandson Harvey Clyde.

At 6:40 in the morning, the water suddenly rose, and it seemed like my house was about to collapse. We all panicked. I looked at my wife Celia, but she said nothing. At 7, we all went out. Celia and I were the last.

When we stepped out of our house, the water was already high. I held Celia. I looked for my son Harold, and saw him running into another house with his wife and my grandson. Celia and I followed. The waves, rain and wind were so strong. It was like Tacloban was under attack.

The water rose when we were on the first floor. It was 8 in the morning, and the water rose high. We made it up to the second floor, when the house collapsed. There were more than twenty of us in the house. Everyone was screaming. There was no way out.

We broke through the ceiling, then through the roof. I saw a hole and squirmed through, then ripped through more of the roof. I pulled out Harvey Clyde, then Harold. My wife nearly got caught on the wood and tin. I carried her out. All of us were crouched on the roof of the house. The wind and rain and waves were so strong that we had to jump to the roof of another house.

My wife was stunned, she wasn’t talking. I told her, “We’ll fight to save ourselves, so that we’ll live.” I held her tight. We were on that roof floating on the water for a long time. I didn’t know where we would end up, because there wasn’t a single building in sight.

After a minute, I saw a wall, with a roof and a terrace. We decided to move to that building. I told my nephews and cousins to hold on to my wife while I attempted to jump to the terrace so I could drag all of them to the building. On my first jump, I fell short, and fell into the water. I was trapped underneath wood and debris, and nearly didn’t manage to break out. I was lucky I did, and made it out of the water. Everyone was far away, my wife, my nephews and cousins. There were mothers holding children, clutching them by their shirts. We were punched by bigger waves. I swam to them, so I could stand on the tin roof again and make another try. I jumped, caught one of the balcony railings, hauled myself up and braced my feet so I could pull my wife to the terrace.

Only my wife wasn’t there. I scanned the waters, couldn’t see anything, not even her clothes. Had I seen her, I would have jumped too.

I couldn’t do anything because I couldn’t find her, and I had to rescue my nieces and nephews and their husbands and wives. I took the children first, grabbed them by their shirts to drag them to the terrace. When I had pulled everyone in, it took another thirty minutes for the water to subside. I left the building and saw my wife’s body, just a meter and a half away from where I was, caught under lengths of wood. I was pained, to see her lifeless on the ground. I never thought she would die, because we were together ever since we ran out of her house, I only lost her just before we saved ourselves.

I took my wife. I asked for help from DPWH rescuers, to take her to safety away from al that wood. I was there when she was carried to the road to be transferred to the DPWH truck. We were taken to the General Services building. There were so many dead in that truck. I didn’t leave her. I was with her until that night, until the next day, I was still there.

The next morning, I couldn’t find anyone who would give me a ride with my wife’s body. Finally I hailed a garbage truck to take us to St. Peter’s Mortuary. All I could do was find a sheet of plastic to lay her body so she wouldn’t have to touch the garbage.

The next morning, at 10 am, I thought my wife was already safely cared for. When I arrived at St. Peter’s, I found out she hadn’t been cared for at all. There were no coffins, there was only plastic from the Department of Health wrapped around my wife. There were so many more dead there. It was good I saw one of my friends who was in charge of a cemetery. He helped me find an empty plot for my wife. I wanted to bury her. At 10 in the morning, the next day, I was the one who carried my wife’s body going to the cemetery.

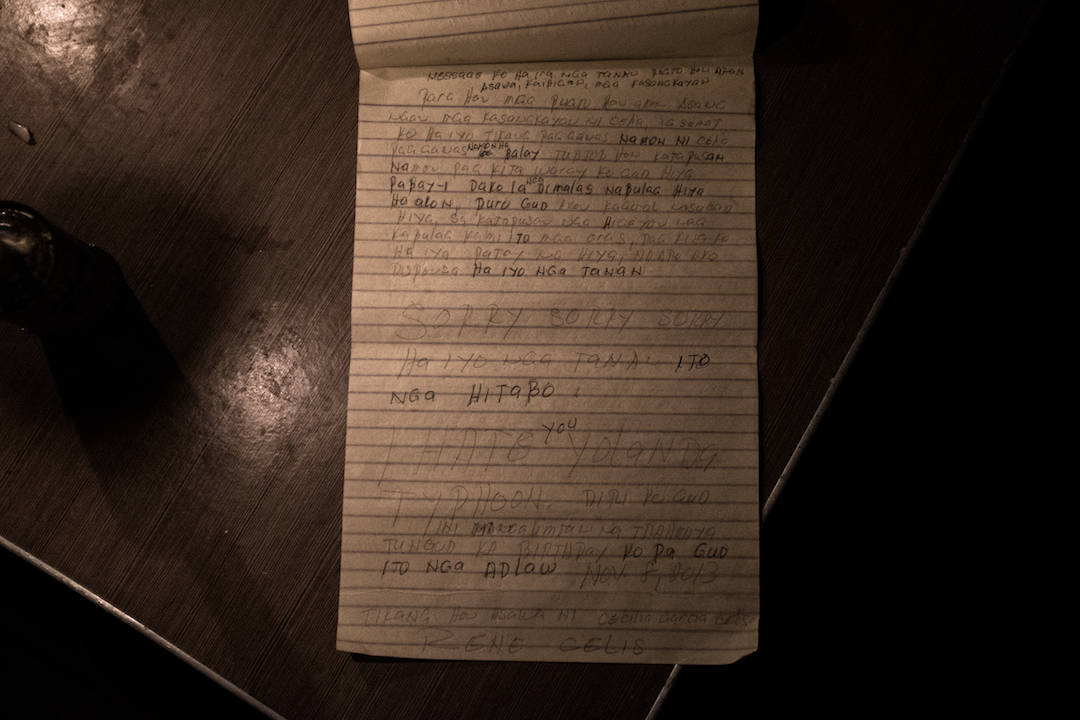

November 8 is my birthday. I was born November 8. My wife died November 8. That’s the reason behind my anger at typhoon Yolanda. It had no pity on Tacloban City, especially none for my village. If it weren’t for the storm, my wife wouldn’t have died. But there was nothing I could do. All I can pray for is that my wife finds comfort in the next life.

To all my wife’s brothers and sisters, I’m sorry for everything. I didn’t abandon her. I tried to save her.

To my wife Celia, I will not forget you, never will I forget you. You cared for me. Wherever you are now, rest. Even if it hurts to think and to feel, I know there was nothing else I could have done.

Photographs by Carlo Gabuco, Philippines | Website: carlogabuco.tumblr.com

Text by Reinfredo Enrique Celis | Translations by Patricia Evangelista and Aiah Fernandez

Share