Community Matters

What Photo Circle and a group of local photographers are doing in Nepal.

What does it mean to have a photography community? And what could such a community do — on a societal level?

I have been a part of many discussions about the need for artists to support each other and to have a space for discussion, discourse, and collaboration. But until last week, I didn’t appreciate what such a shared space, such a collective, may be capable of.

I spent 5 days with Photo Circle in Nepal. Over the last 8 years, they have created a space for Nepali photographers to learn, grow, find international opportunities, and begin to work in an interdisciplinary manner — combining a passion for social change with an understanding of visual history – and to see the intersection of photography with other art forms.

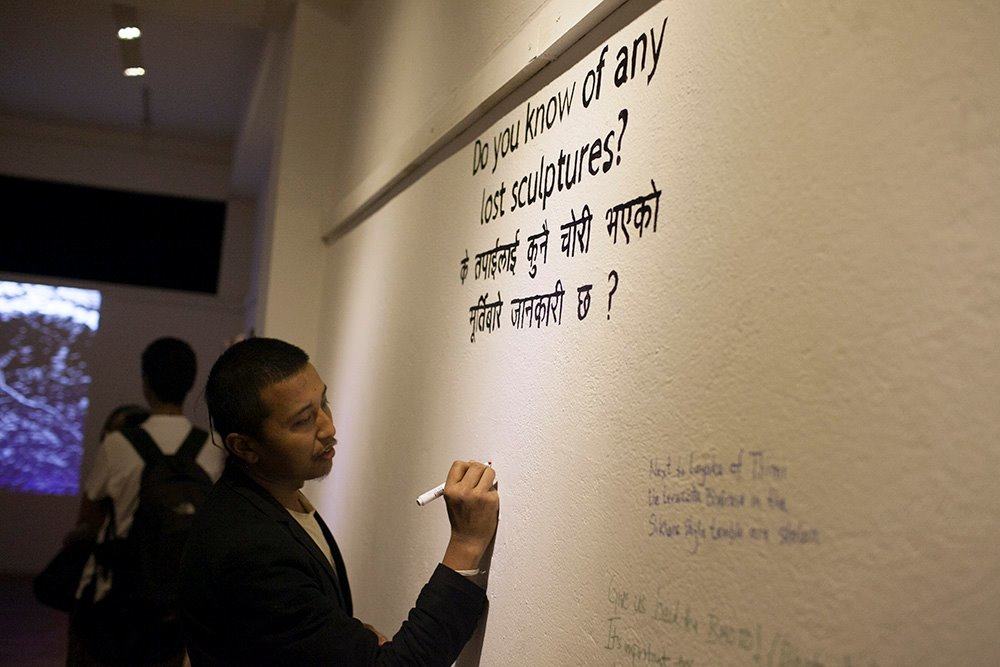

Photo Taken By: Sagar Chetri. Caption: Photo Circle’s ongoing exhibition, “Remembering the Lost Sculptures of Nepal”, in partnership with the Himalayan Art and Cultural Heritage Project. Paintings, interviews, and photographic documentation by Joy Lynn Davis weave together narratives of Kathmandu’s sacred spaces, exploring how people respond when religious art objects — that exist, not as commodities, but as vital living community participants — are physically removed.

When the earthquake hit, I was in an old building in Patan with the founders — NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati and Bhushan Shilpakar. We ducked under the tables. As he felt it passing, Bhushan shouted, “NOW! RUN!”.

We were out in a minute. The building had cracked. A gash several feet deep ran along its left side.

My legs shook uncontrollably. I looked up. Some of the group had risked going back up to help a construction worker stuck under the debris.

We were a group of about 25, all there for a workshop. Artists, writers, photographers, designers, professors, civil society members. Head count. Everyone was safe. We had all made it out.

Within the hour, another two tremors hit. I was terrified.

In the next hour, NayanTara and Bhushan had gotten to work. They began to survey the damage, fielded calls, checked in with their families, and the families of many others who reached out to them. Bhushan stepped out of the safety of the tennis court we were sheltering in, away from all standing structures, and helped the emergency forces rescue a woman who had collapsed under a sattal a few kilometres away.

NayanTara arranged space for us to sleep. Hot food. Drove me to the airport at 8am. And without a moment of rest herself, she set up a meeting for volunteers at 9am at the Yellow House, Sanepa.

I was battling the airport authorities for a seat on a plane out by then. After coming back to Bombay, I have watched in amazement at what Photo Circle, surrounded by friends from the art community in Nepal and tens of other citizens wanting to pitch in, is accomplishing.

By noon, the morning after the quake, they had set up Nepal Photo Project (@nepalphotoproject) — an Instagram account documenting the aftermath of the earthquake in Nepal. Using the hashtag #nepalphotoproject photographers from the region, as well as aid organizations, can get their images noticed by the feed. If the image is coming from a trusted source, or can be verified, is providing important information or appealing visuals, it will be posted on the account. If anyone notices an image that they think should be on the feed they can comment on it, bringing it to the notice of @nepalphotoproject. You can also email images to [email protected].

After all these months on Instagram, I can finally appreciate the usefulness of the ubiquitous #.

The valley of Bhaktapur. Some breathing space amidst all these visuals of devastation.

Growing up in Kathmandu was magical. At the time, literally a small quaint Kingdom. A home with a small cow shed and an orchard in the backyard. A larger than life tree towering over an old temple, stretching it’s long arms over the entire neighbourhood. At dawn the sounds of brobdingnagian temple bells, struck loud enough to invoke the gods from their sleep. All that against the backdrop of a cacophony of the zillion birds that lived on this tree. Giant wheel chariots, living goddesses and royal processions. The infamous Titaura (local sweet and spicy candy) for which would endeavour any Everest. Demons and Yeti’s were still real and come autumn, the breeze would fill the skies with kites. Not a day went by without adventure.

Photo by @sumitdayal via Nepal Photo Project

Like everydayasia, everydayafrica, and the many other everyday accounts out there — the Nepal Photo Project account privileges a depth of knowledge and the perspective of those living the daily realities on the ground over exoticized, stereotypical or — as in the case of present day Nepal — endlessly hopeless representations. However, different from the “everyday” accounts, this project is based around an emergency and — for now — is considered a part of the relief effort, a place for people to go for reliable information. They have posted images of missing people whose families are desperately looking for information, images of broken piggy banks, childhood reminiscences and stories of hope. It is a subtle and powerful assertion of the local in the unfortunate global reality of a media and NGO environment that may still hire photographers that are completely unfamiliar with a country to fly in to a disaster to make sensational images.

Aside from this photo initiative, all volunteers meet at the Yellow House in the mornings and evenings to organize urgent emergency relief. Assessments are made, materials distributed, and teams sent to locations still without aid. A page for donations has been set up. A Facebook page provides continuous updates about the work being done — with images taken on location. The numbers of volunteers and contributions has been going up — daily.

Leaving behind the decades-long-debates pitting a photographers ability to make images against the ethical responsibility to act in crises, here is a group that photographs, but does not hesitate to see whether they can work to mitigate the pain, to provide relief. Perhaps because they are working from home, from their own present and are a part of what the future will bring for their country. There are still many battles to be fought but they are braved from a place of knowledge and belonging.

Prakash Jha, veteran journalist, in the prologue to his contemporary history of Nepal writes, “After the crowds return home, after the frenzy which accompanies a moment of political victory dissipates, after the camera lights shift and reporters move on the next story, the hard work of politics begins.” He is writing about the time after the success of the People’s Movement had brought democracy to Nepal less than a decade ago. This time it is not a victory but the adrenaline will ebb just the same. As the depth of damage and stories of despair fade away from the front pages, the printed paragraphs growing shorter in length, the next eye-catching image dominating the covers, the hard work of rebuilding will just be beginning.

And I believe this exceptional community with whom I was privileged to spend just a few days will hold fast. Deep as their roots have grown and intertwined, they will be there to listen and act.

As a writer from the workshop, Prawin Adhikari — also the one who kept us calm in those desperate seconds on Saturday — says so poignantly,

“What once had been: that we will mourn. But I will not despair although I mourn. Life moves inevitably ahead.”

Text by Alisha Sett. Alisha is a writer based in Bombay and co-founder of the Kashmir Photo Collective.

More from Alisha: https://medium.com/@alishasett

Share