Pablo Bartholomew, 52, is one of India’s leading photographers and the first from South Asia to win the World Press Photo (WPP) Award in 1975, when he was just 19. However, his name remains obscure to the wider community of image consumers and curators.

Nowadays, when it comes to the subject of Indian photography, people will marvel at the mammoth projects that Raghu Rai has done on Taj Mahal and Mother Teresa, the intriguing compositions of Raghubir Singh’s colour photography, or the environmental portraits of India’s elite – complete with traditional and post-colonial symbols of prosperity – by Dayanita Singh. The fact that his name is not more readily brought to mind is surprising, as Pablo Bartholomew is one of Asia’s most decorated photographers. He won the WPP on two occasions and has served as a member of the jury in 1999 and 2000. Prior to 2006, his work has already been shown at Musée de l’Homme in Paris, Asian Arts Museum in San Francisco, Queens Museum of Art in New York and at Visa pour l’image – the International Photojournalism Festival at Perpignan. Moreover, his client list – which includes Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, LIFE, GEO, Stern, Le Figaro and The New York Times Magazine – is an object of envy for any photojournalist in the world.

Despite that, Bartholomew’s place in Indian photography is by no means assured. Not surprisingly, when he speaks about his work with these big-name clients, it is hard not to detect a sense of jadedness.

“Now I’m in the mainstream – I understand what the editors want and I go out to produce the clichés that they need,” comments Bartholomew. “At the end of the day, it’s nothing spectacular.”

Especially after winning his second WPP Award in 1985, Bartholomew found himself increasingly sucked into the rut. At that time, he was working for Gamma-Liaison, one of the top photo agencies in the world, and he was very much its star photographer.

“Since the 80s, any sort of sneeze from India would be quite widely reported,” recalls the photographer. “India was then the number one ally of Soviet Union and the leader of the Non-Aligned Movement. Cuba was also a friend. Being based in Delhi, there was always a lot of work to be done as a photographer.”

Therefore, by the time he left agency work around 1999, he has already “lost his eye”. His sense of composition and colours has become so well oiled that the raw edginess and the “joy of seeing” in his earlier work is gone. In the summer of 2006, Bartholomew asked his assistant to scan the first 35,000 black-and-white negatives that he shot as a young photographer and then kept aside for the last 25 years, thereby taking a deliberate step to rediscover and consciously promote what he terms as his personal work.

“To engage the fringe – a lot of young photographers are doing that right now to the extent that the themes have become clichés,” says Bartholomew, relating the perspective of the curator. “But that was my life. I was in it.”

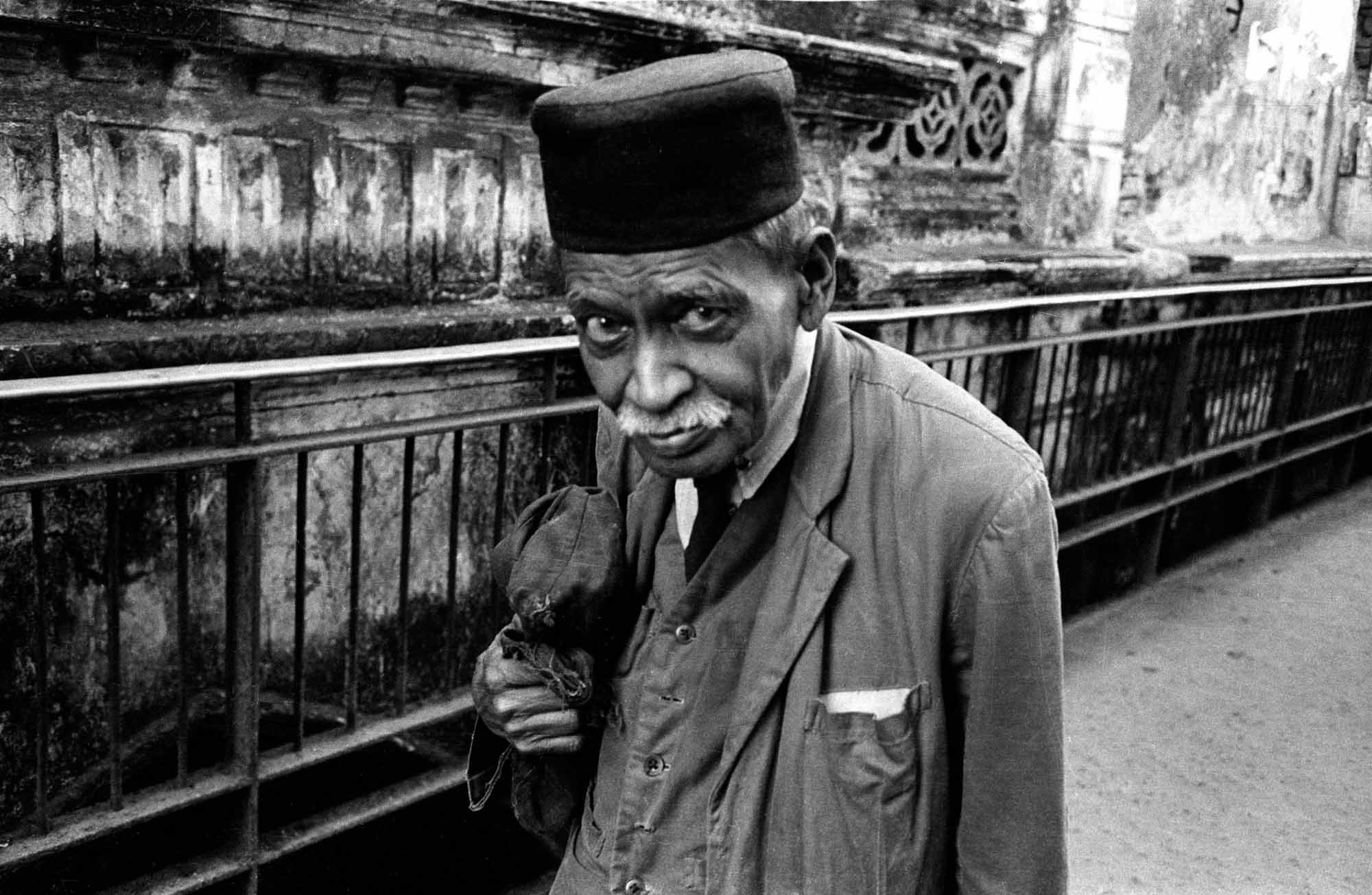

Titled Early Work (1972-1981), a selection of which was first shown in Holland’s Noorderlicht Photofestival when it featured photographers from South and Southeast Asia in its 2006 edition. According to Bartholomew, he asked curator Wim Melis for the reason of selecting his work. Melis said that Bartholomew had shot those images with a definite and historical point-of-view.

“To engage the fringe – a lot of young photographers are doing that right now to the extent that the themes have become clichés,” says Bartholomew, relating the perspective of the curator. “But that was my life. I was in it.”

An alternate selection then went to Dhaka-based Chobi Mela IV and a different edit has just been shown at Rencontres d’Arles 2007. The programme note of the latter explains: “Expelled from school for insubordination when he [Bartholomew] was fifteen, he discovered a far more fascinating world of weirdos, druggies and white hippies.” The series on Morphine addicts in India, which won him his first WPP Award, belongs to Early Work.

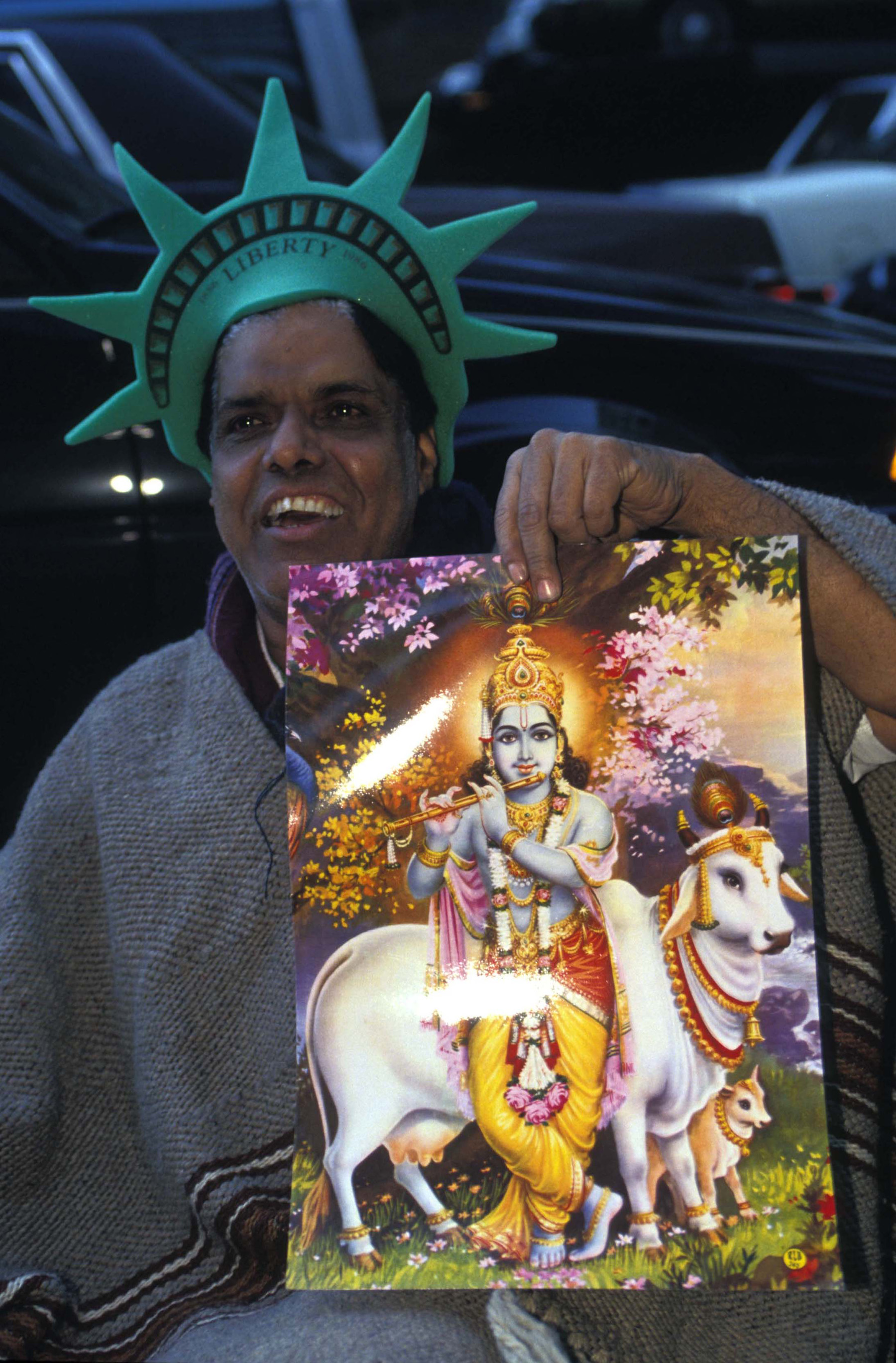

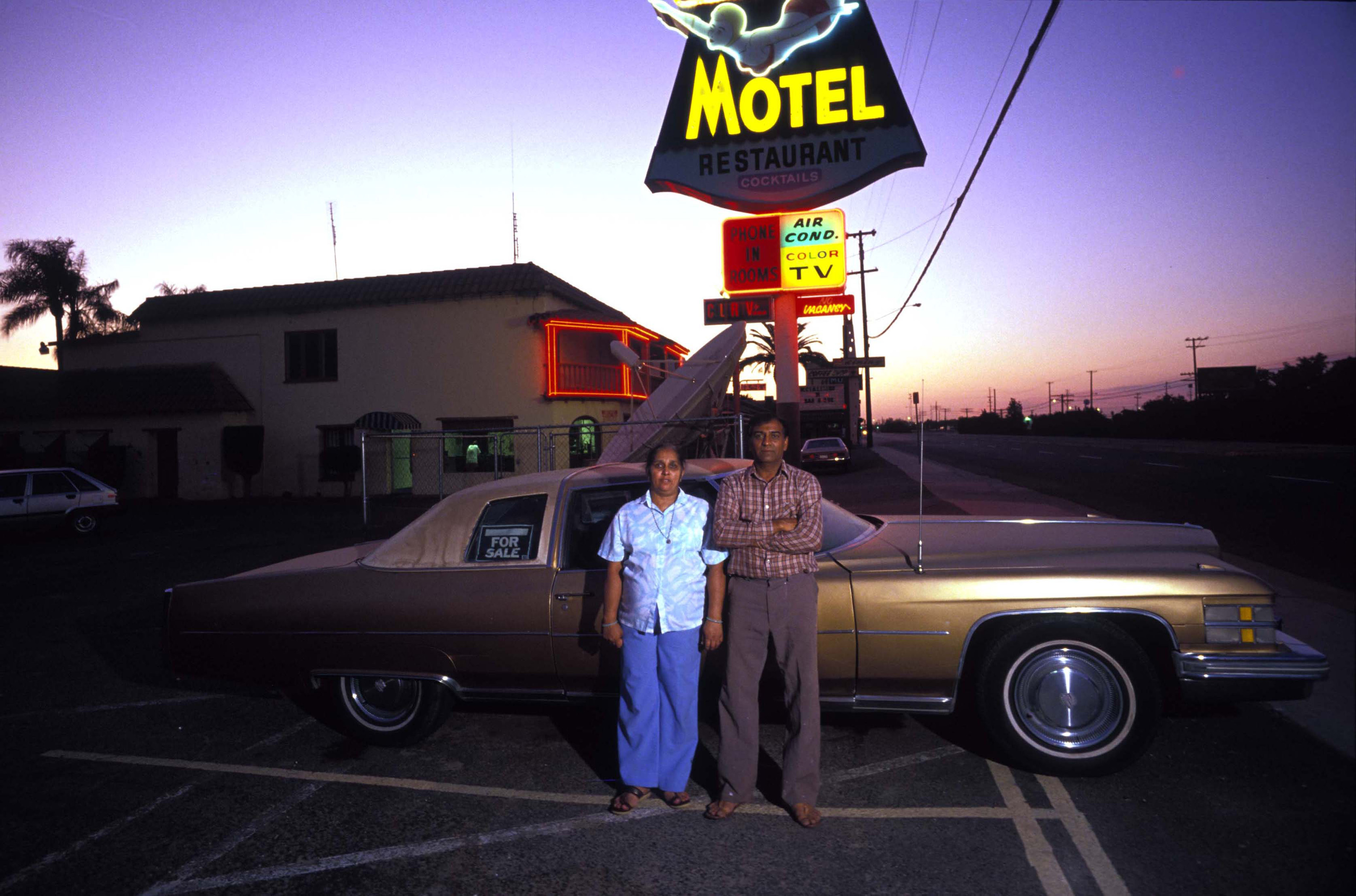

At the same time, another of his self-initiated series titled The Nagas – Marked with Beauty (1989-2001) travelled to the Angkor Photography Festival in 2006 and has been featured in Tokyo’s Month of Photography in 2007. A third set of work titled The Indian Émigré (1987-88), which he sees as part of his personal canon of projects, is now being exhibited as part of a show on Indian contemporary photography and video at the Newark Museum from September 2007 to January 2008.

Pablo Bartholomew talks to Zhuang Wubin about the vulnerabilities that he felt in the last few years and his intense desire to rejuvenate himself as an artist.

Zhuang Wubin: While The Nagas – Marked with Beauty is essentially a documentary project about the people of Nagaland in northeast India, it was also an attempt to understand your roots. Do you have Naga blood? Your father was born in Davoy (Tavoy), the southernmost part of Myanmar. If you wanted to explore the issue of identity, why didn’t you pursue Myanmar as your personal work?

Pablo Bartholomew: Together with other Burmese, my father and his family left Myanmar for India during WWII. They walked through Yangon (Rangoon) and Mandalay, and ended up at Ledo in northeastern Assam. Upon meeting the Naga people, my father’s family was treated with kindness. They were given shelter and food. If there were no food in the village, animals or birds would be slaughtered for them. These were the bedtime stories that my father told when I was younger. However unreal my ideas of the Naga people might have been, there were certain images that I had conjured up since I was a kid.

At the same time, I’ve always been fascinated by borders. India maintains such a long political boundary with other countries that it’s hard not to be interested. In these areas, cultures are never fixed or stagnant.

In 1983, I was asked by National Geographic to attempt a story on Myanmar. We didn’t succeed but I was still able to take a peep of the country. She was not a particularly rich or poor country but her peoples led a very traditional way-of-life. The temples and monasteries were very vibrant but people would not talk or engage with me. When I returned in 1989, things seemed more desperate. Pimps started turning up at my hotel to offer young college girls for sex.

I haven’t engaged Myanmar as a personal project because I have yet to find an angle to “enter” the country. I have 20 to 30 strong images of the country but I can’t call this my personal work. Whenever I was in Myanmar, I felt like a highly trained professional looking in from an outsider’s point-of-view. Anyone can do what I have done in Myanmar. But I doubt anyone understands the culture of the Naga people as much as I do. A few years back, Belgian photojournalist Thierry Falise did a similar piece of work but the story is flat.

“As a thinking photographer, you have to deal with questions of identity, somehow or another, in your work. That’s why I can’t see how half the European photographers can live between HK, Cambodia and Bangkok. For them, they engage the region for various reasons.”

The Nagas – Marked with Beauty fulfilled the emotional role of the personal work I have not done in Myanmar. As a thinking photographer, you have to deal with questions of identity, somehow or another, in your work. That’s why I can’t see how half the European photographers can live between HK, Cambodia and Bangkok. For them, they engage the region for various reasons. Maybe it’s easier to have a better lifestyle here, since they get more out of their Euros. However, there’s always a distance in their work. Very few go beyond that. Photography is all about spending enough time.

In any case, this series is very much work-in-progress. When I first started the project, I took a lot of images in the visual anthropological tradition, documenting their rituals and practices carefully. That decision was important because with the onslaught of Christianity, everything was disappearing. Today, I have some of the most obscure images of the Naga people that nobody else has, like the skull-house, which was gone by the early 90s. I was supposed to start on the “modern” side of their lives a few years back but I found myself burnt out. Anyway, I have started going back to Nagaland in 2006. It will be interesting to juxtapose the two parts when everything is done.

After your family moved to Delhi, you led a safe, middle-class life. What turned you to the fringe?

At that time, people seldom marry outside their ethnic groups. But my grandma did. And my mum – whose family came from Pakistan, West Bengal in Indian, and Bangladesh – did by marrying a Burmese from Myanmar. My mother fled Pakistan during the Partition in 1947. As refugees in New Delhi, they met in college in the late 40s and married for love, which was rare in those days. Today, I have relatives from Pakistan to Punjab, from Dhaka to Chittagong Hill Tracts, and from Kolkatta to Myanmar, where I assume I have family members whom I’m unaware. I’m from all these places but in a way, I’m from none of them. At home, I spoke English – that was my first language. And I have this funny name, which doesn’t suggest that I’m Indian.

I grew up in a socialist family. We didn’t have a phone until I was 14. We always rented a place rather than bought a house. Everyone in class had a car. We didn’t. I also came from a very artistic family. My father, Richard Bartholomew, was a painter, poet, writer, curator and above all, one of India’s most prolific art critics. My mum, Rati Bartholomew, was an English professor at Delhi University, founder of several important theatre groups and most importantly, a street theatre activist who worked with groups across the sub-continent.

At the same time, my parents practised no religion. I guess my parents were probably very alienated from mainstream India in the first place. My upbringing left me with the freedom to look at India with unattached engagement. It allows me not to be biased against caste, religion or regional points-of-view. Being not from any geographical location allows me to appreciate everyone and everything.

When I was kicked out of that famous school, I became a scandal. Delhi was then a small and stratified society. Everyone came to know me. Thankfully, the cultural collateral back home was a rescue net. With so much confusion in my head, photography provided me with a sense of purpose and identity. I started photographing my friends, family, artists and painters who would visit my father, art openings and rock shows. But my restlessness was not fulfilled.

One of the great cultural upheavals that were happening in the 70s was the hippie movement. The influence of drugs and music was wide and profound. It was my way of connecting with the Western world that was looking to the East, post-Vietnam. I smoked dope then and I still do now. That kind of isolation naturally led me to the fringe. The images went into Early Work.

Despite winning the WPP Award, it didn’t do much for your career and you found yourself working as a stills photographer on the film sets of Satyajit Ray in Kolkata (Calcutta). Through Ray’s introduction, you subsequently shot stills for Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and Merchant Ivory’s Heat and Dust. What did you pick up as a photographer on the film sets? Were you still casting your eyes on the fringe?

Working on the sets was the first time I earned some money. I did theatre when I was younger and I treated films as an extension of that.

It was very enlightening to see how Satyajit Ray worked. He was a classic filmmaker who wrote his scripts, composed the music and shot his films. Any film student would give his or her left eye to see Ray worked. Looking back, I was paying my dues at the sets, teaching myself everything about photography. But I never did turn my head away from the fringe. In Mumbai, I started photographing the extras and the stuntmen. I also visited the opium dens, the red-light districts and the eunuch quarters.

As a young photographer, I took pictures to satisfy my inner needs. When my work on the fringe was shown in Delhi in 1980 and then in Mumbai on the following year, it was a defining point in terms of our engagement with the “other” world. No one had documented the fringe previously. In retrospective, the work was path breaking.

With The Indian Émigré series, were you trying to explore your identity from a different angle?

I’m not sure if you read more into things or you actually realize more when you grow older. In all three sets of my personal work, there’s a definite desire to explore my state-of-mind and my notion of identity at that point of time. Funded by the Asian Cultural Council – formerly known as the John D. Rockefeller III Fund – in New York, I was able to pursue this project. While exploring my identity, I decided to take the process outside of India – to look at the Indian migrants in America and to examine what they kept or discarded when they migrated. With the project, I’m dealing with the feeling of being and belonging. I’m looking at the two worlds that we all live in – the one that we bring with us and the world that we assimilate. Moreover, I was working then for a New York-based photo agency but I knew little about America. The project allowed me to approach the country differently. For the first six months, I sat through the archives just to research on the subject. In total, I spent nearly two years on The Indian Émigré.

In another interview, you spoke at length about your father as an influence to your life. Was he your first teacher in photography?

As a photographer, he would take pictures of his artist friends. When we went to our summerhouse, I would be with him in the darkroom, looking at the images emerging in the developing tray. That was pure magic. He didn’t teach me anything specific about photography. What I took from him was the need to be a more sophisticated man – a Renaissance man, like him – whom I’m not. I think that showed in his images. His pictures were more complex and had more layers than my work.

What prompted you to revisit Early Work in 2006?

When I passed 50 two years back, I felt vulnerable. Perhaps this is psychological. Even though I have reached a certain high point, I feel I can go down very quickly. Physically and mentally, I’m slowing down. How then do I use my experiences to a better effect?

About ten percent of the images that my assistant has scanned are too private to be seen. In any case, all of them told my coming-of-age story. Some of the people in my pictures have become incredibly famous. Some didn’t survive the drugs. I’m still finding a way to piece everything together.

“In recent years, there are many young photographers who like to hang out with me, perhaps hoping to get some words of wisdom or bullshit from me. But I’ll like them to know that you don’t have definite answers all the time.”

In recent years, there are many young photographers who like to hang out with me, perhaps hoping to get some words of wisdom or bullshit from me. But I’ll like them to know that you don’t have definite answers all the time. When I left agency work in 1999, I took many years to find my balance. I put aside my photography and went to develop a technology for photographers and agencies to store and distribute their image resources. It is complete with tracking tools, so that photographers and agencies can see where the client search has fallen through. We have been offering a pricing and e-commerce platform to our clients before the more popular Digital Railroad followed suit in recent months.

From 2001 to 2004, I could only spend 30 percent of my time on photography. The rest had to go into developing the technology. Now, the time spent on photography has gone back up to 70 percent. It’s good but the fear of failure is never far behind. It keeps you at the edge.

Is this desire to revisit Early Work related to how photojournalism has changed in the last 15 years with the mergers and acquisitions of photo agencies?

I guess there’s a sense of nostalgia as well. In 1987, I was commissioned by LIFE to do a book on South Chinese cuisine. I was flown to London to see the art director and a food specialist. The assignment was to last for six weeks. Eventually, it was extended by another three weeks. Then the editor called to say that the project was off, having paid for everything. Those were the days.

Nowadays, there are too many photographers in the market. At the same time, there’s a lot more fluff now even in magazines like Time and Newsweek. You have to be based in a country where the media is interested to be able to survive as a photographer. That’s why so many photographers go to Afghanistan and Iraq. Now and then, I meet foreign photographers in Delhi and they will tell me that they are doing some NGO work and a bit of editorial stuff. Two years later, they will pack their bags and disappear.

Today, I see Early Work as the most important project that I have done. Photography can be done in a personal way. You may earn your money elsewhere and keep photography as a passion. And you shoot the shit out of everything around you. Don’t be afraid to take a long-term view of the work.

With the “rediscovery” of Early Work, you have also become more proactive in promoting your work. Why so?

I’m growing older. If I don’t do it, who else will? So much of history is now dependent on marketing. In Australia or America, when they discover a talent, they will push for his or her work. And this doesn’t happen in India. It’s up to you to do it. Take a look at my father. He was one of the most important art critics but he’s already forgotten. What I will do in the coming months is to bring out a book of my father’s photographs of the Indian artists. At the same time, while my three sets of personal work are travelling to different shows, I’m also using the opportunity to visit the photofestivals and to see what’s happening in the photographic world before deciding my next move.

More from Pablo Bartholomew: http://www.pablobartholomew.com

Share

Comments 28

Pingback: Pablo Bartholomew | Cada día un fotógrafo

Japanese photography is really something. Know Daido, Araki, and Rinko Kawauchi. Need to know other photographers with works such as of the fine master Shomei.

Pingback: List of 30 Most Influential Photographers in Asia 2014 | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA)

Pingback: Pablo Bartholomew to Attend Chobi Mela « drikbd

Pingback: Pablo Bartholomew to Attend Chobi Mela | ShahidulNews

Pingback: chobimelablog |

Interview with Pablo Bartholomew, one of India’s leading photographers | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA) http://t.co/JjIGm6NS

RT"@Amrita_Dass: @InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/PgmKx6d2"

great pics and interesting inteview, great work

@InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/trYNGbGE

RT"@Amrita_Dass: @InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/PgmKx6d2"

@InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/trYNGbGE

@InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/trYNGbGE

@InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/trYNGbGE

@InvisPhotogAsia 's interview with Pablo Bartholomew, the man whose images speak for history/ http://t.co/trYNGbGE

Interview @invisphotogasia with Pablo Bartholomew, one of #India most decorated photogs http://t.co/7qcdnOVJ

Interview @invisphotogasia with Pablo Bartholomew, one of #India most decorated photogs http://t.co/7qcdnOVJ

Pingback: Invisible Interview: Raghu Rai, India - Part 2: Criticism, Religion & Colour Photography | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA)

Interview with Pablo Bartholomew, World Press Photo (WPP) Award winner in 1975: http://t.co/4tldtFfB @InvisPhotogAsia #photography

Interview with Pablo Bartholomew, World Press Photo (WPP) Award winner in 1975: http://t.co/4tldtFfB @InvisPhotogAsia #photography

Interview with Pablo Bartholomew, World Press Photo (WPP) Award winner in 1975: http://t.co/4tldtFfB @InvisPhotogAsia #photography

Interview with photographer Pablo Bartholomew, 1st from South Asia to win the World Press Photo (WPP) Award. http://t.co/JnpBJPlK

Interview with photographer Pablo Bartholomew, 1st from South Asia to win the World Press Photo (WPP) Award. http://t.co/JnpBJPlK

Interview with photographer Pablo Bartholomew, 1st from South Asia to win the World Press Photo (WPP) Award. http://t.co/JnpBJPlK

Interview @invisphotogasia with Pablo Bartholomew, one of #India most decorated photogs http://t.co/7qcdnOVJ

Interview @invisphotogasia with Pablo Bartholomew, one of #India most decorated photogs http://t.co/7qcdnOVJ

@InvisPhotogAsia – Interview with Pablo Bartholomew http://t.co/rDDAI4Fu #Asia #photography

Interview with Pablo Bartholomew http://t.co/j7TxPheJ