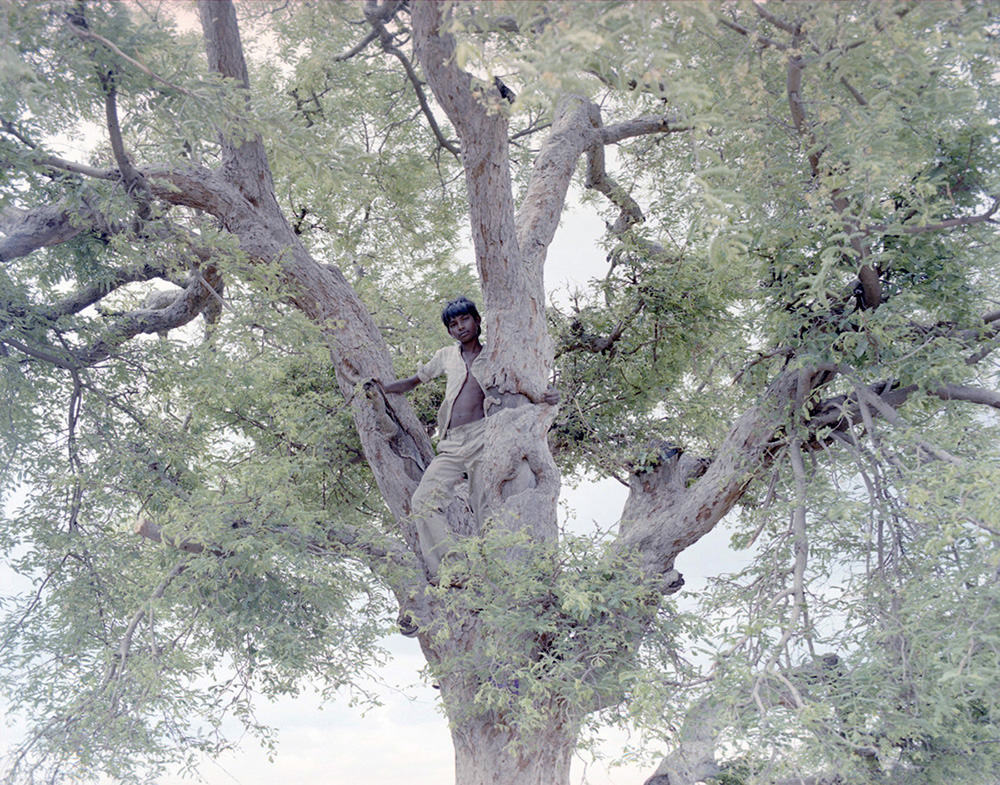

River of Lost Time (2005-07). © Sohrab Hura

Getting Personal with Sohrab Hura

Young photographer Sohrab Hura from Delhi was recently elected a nominee member by Magnum Photos. Sohrab is the second Indian Photographer to join the roster with the famed agency – Raghu Rai, the other.

Social media in photo land India, and Asia for that matter, welcomed and celebrated the news with vigor and hashtag #sohrabhura to boot. Some though, asked “Who is this Facebook-less Sohrab guy?”

I met Sohrab earlier this year at a Photo Festival in China. Sohrab was exhibiting some early photographs of Varanasi he had made. Lost in translation, the Chinese festival organisers had written a line in his bio that read ‘Magnum would come looking for him’. The few of us there joked about the mistake, but in hindsight, they probably sensed something we didn’t.

After the media dust settled (I guessed), I asked Sohrab if he had time and breath for one more interview. He obliged, thankfully. I sent him the interview questions immediately around midnight. He replied with his answers almost immediately too. This Facebook-less #sohrabhura guy doesn’t sleep, or wakes up really, really early.

So how does it feel Sohrab?

Sohrab Hura: I’m not sure. I’m happy but at the same time there is a bit of sadness to be leaving a very beautiful space I’ve been in for the last few years.

If you could go back in time to that kid in the Gurgaon supermarket who showed his mum the Magnum book and said he wanted to be in there, what would you tell him?

Nothing. I wouldn’t want to change a thing, and I’d want that kid to discover and experience everything on his own including the mistakes if at all I made any.

How did you go about editing and selecting your work for submission to Magnum? Tell us your thought and working process.

Well… I was really confused in the beginning because I have many works of different kinds done over the years and I didn’t know what to submit. And each of those works have lots of photos. The submission guidelines say that an initial submission of only 60 photos is allowed so that was a bit intimidating for me, especially because I’ve been working against the idea of editing down. The way I work needs the number of photos to be on the higher side.

So Olivia Arthur and Susan Meiselas gave some suggestions regarding the works I should submit. In fact, Olivia has helped shorten the edit to about a hundred photos that included 6 works. She suggested that I project myself as the photographer I am, one who is looking at the world in many ways. And that really helped because I didn’t want to have to second guess the Magnum members. However, because of the 60 photos limit I could only send 3 bodies of work.

A few days before the meeting, I was asked to send whatever supporting material I wanted to within two days. So I sent a short edit of about 200 photos from 5 works and a piece that included 60-80 photos and video footage. Kosuke Okahara was really kind to have sent across a book dummy that was lying in Paris through one of the people at Magnum flying to New York to the meeting. I think this allowance to show supporting material is what helped me.

How has India’s Photography Fraternity taken to your nomination?

I’m very humbled and overwhelmed by the response. They have been extremely generous. I did not expect this and I’m still a bit surprised because a lot of them seem to be more excited than me. I had immediately gotten into the mode of working the next two years because I need to show them new work and wasn’t able to really soak in the news.

What does it mean to you to be part of an agency, and Magnum at that?

At the moment, nothing much. I mean of course I’m very privileged to have this platform but I can’t really afford to think about it more than this. I have to work really hard to keep myself the same as I was before this Magnum thing happened.

By default, you will be looked upon as a role model, in India and Asia I would guess. How do you feel about taking upon the role?

It is something I would never do consciously to be honest. I think the best way to give back to the medium and the community is by just doing work. And I just want to try and make work and be myself. If I start to take on all these things consciously it will never again be just about me and the work, and I won’t ever do justice to what I want to do.

You mentioned “Raghu Rai made us love photography and once we became intellectuals, we turned to Raghubir Singh.” Can you elaborate?

You can’t escape Raghu Rai‘s work whether you are a photographer or not. That is his strength. Once we learn the history of photography and realise the importance of Raghubir Singh‘s contribution we appreciate him more. In some ways he is more a photographer’s photographer.

I was also taking a light dig at myself (and some friends) for over-thinking photography sometimes, and not enjoying the simple things as much as we used to earlier, when there was more innocence in our reading of photography.

You also mentioned a bit about honesty in photography so let’s talk about that. How does one gauge, and in turn, nurture honesty? And are we, ourselves, best judges of our own honesty?

How does one gauge, and in turn, nurture honesty as a person? I think we can only try to be the best judge of ourselves as we can. There is no formula to it. In my case there is a natural tendency in me to believe that my work is not good enough. Actually it is more a tendency to believe that my work could be a lot better, and not the former. And this really helps. There is always scope to do something better.

“How does one gauge, and in turn, nurture honesty as a person? I think we can only try to be the best judge of ourselves as we can. There is no formula to it. In my case there is a natural tendency in me to believe that my work is not good enough.”

Having had the ironic privilege to have started photography from a raw place where it was more a need than a want, I began from a place that was already close to my core. For me, honesty in a work is about making that work just for the sake of making it and nothing else. And I think my beginnings or rather the reasons for those beginnings gave me a huge head start in making my work for those reasons. This is the closest I think I am able to articulate the answer to your question. Any more would be similar to my trying to literally explain the meaning of “instinct”.

Sweet Life: Chapter Two – Look it’s Getting Sunny Outside!!! (2008-2014) © Sohrab Hura

When we met in China for the first time earlier this year, I found you confident and playful, yet a little insecure at times. Do you agree? And what are your thoughts on confidence and insecurity, as a photographer?

I’m a bit confused about what you are referring to. If it’s about my photography/work/vision then you’re right. But I wouldn’t call it insecurity. For me it’s doubt because doubt is a very specific kind of insecurity. If I lose that doubt, then I also die as a photographer. I’m ferociously protective about the direction of vision, and for that I obviously need confidence, but in that vision (and its direction), in that protective parameters of confidence, it is really important for doubt to exist, to fuel whatever it is that is driving me. It is not confidence that pushes me but the doubt, but the confidence protects the doubt. One can’t live without the other and I can’t live without either. For me this doubt is coming from within, but insecurity can very often be about being affected by outside influences which I try very hard to protect myself against.

I think in some ways it connects to your previous question about honesty. For me the question “is my work good?” is not that important. What is important though is the question “what is not good in my work?” It is important for me to be consistently chipping away at my work, at my mind, at myself with this question.

If it’s about me as a person in general, then I apologise and I’ll work on it :)

What to you is the difference between photographing at home as opposed to the outside world, of strangers?

This is a difficult question to answer and for me, it’s always in a flux according to my state of being. When I first started photographing at home there were some extra concerns that developed within me as I photographed, though none were the reasons for the work itself to come into existence. The first was that I felt that I needed to photograph my own mother before photographing someone else’s mother.

At that time I was already having many other problems with my photography (2005-06). I had been working on employment and livelihood issues in rural India, and I was finding it more and more difficult to come to terms with it because I’d go to places where life was extremely difficult for people on a daily basis, and then I’d come back to my protected world and doing this over and over really screwed with my head. I started to feel that I needed to photograph my own home, my own problems before trying to photograph someone else’s. I think it’s always easier to photograph someone else’s misery and not one’s own, and I didn’t want to feel like a hypocrite. It was important for me to photograph someone close to me I could be accountable to, although that didn’t work out because no matter how bad I made my mother look she’d always love whatever I did. Because after all, I was going to another place, photographing people in not the best of states, and then taking the photos to another world, the cities, to a different audience, and no matter how accountable I tried to be, I don’t think there is true accountability on us photographers when we’re doing this kind of work, at least accountability in the sense where the people in the photos get the opportunity to tell us a simple thing like they don’t like the way they look in the photo.

“Almost all photographers, when they work on this “issue”, try and bring out a sense of madness which I didn’t agree with. There is more to people with any kind of mental illness than madness, if at all, there was that madness. So I wanted to photograph my mother not as a photographer, but as a son.”

Then came another baggage. I had started to hate photographs of people with mental illness in general. Almost all photographers, when they work on this “issue”, try and bring out a sense of madness which I didn’t agree with. There is more to people with any kind of mental illness than madness, if at all, there was that madness. So I wanted to photograph my mother not as a photographer, but as a son.

I think over the years I’ve embraced this question in different ways. In my current state of being, I don’t care so much about the question anymore, or more specifically, I don’t care about this dichotomy between photographing family and photographing strangers. They both feel more or less the same to me. But I do feel a little bad some times when I see photos taken by photographers of home/family where the tone and the feel of the photos is one close to that of an assignment or a “project” because I feel that home is an extremely privileged space to be a part of as a photographer because he or she is naturally an intricate part of it, and it is a pity that he or she is still photographing otherwise.

Video Clip: Pati (2006,2010) © Sohrab Hura

[vimeo clip_id=”36863984″ height=”” width=”900″]

.

And what are your thoughts on aesthetics and language?

They’re both very different for me. Aesthetics/style is nothing but something superficial. But language is how you say something you want to, and aesthetics is just a small part of it. Language is something that comes from within, and is close to one’s core and aesthetics can very often have no meaning other than something decorative and nothing else. Of course, aesthetics can be extremely seductive but if a work is just about aesthetics it will never live too long.

Can you elaborate on your quote “Sometimes, you can destroy a photograph by being a photographer.”

Actually my words get changed very often. What I said was “sometimes you can destroy your photography by being a photographer.”

When I first sensed this, I was questioning my photos when I was working on “Life is Elsewhere”. I felt that they were too “trained” and the photographer in the work was too visible, and it was not the son photographing his mother but the photographer photographing someone who happened to be his mother. When I looked at the photos I felt that the photographs were catching my attention but they were not raw enough. I had also started working with the Anjali House children and there was a big difference in the way they saw the world. It was a lot more raw, without many of the other protective layers of aesthetics or whatever else that we photographers sometimes necessarily employ when our works are not good enough or sometimes unnecessarily employ when our works are actually good and don’t need anything else. I wanted at that time to try and see the way a child looks at the world. But the photographer in me had been so ingrained over years of conditioning that I could only try and do the best that I could.

“Today this feeling about one’s photography being destroyed by being a photographer is even more relevant and urgent for me. Towards the end of any work, I can sense that my conditioning to working that way has allowed me to get a sense of what makes a good photo or a photo that works, and the moment that sense comes to me with ease is when I need to get worried.”

Today this feeling about one’s photography being destroyed by being a photographer is even more relevant and urgent for me. Towards the end of any work, I can sense that my conditioning to working that way has allowed me to get a sense of what makes a good photo or a photo that works, and the moment that sense comes to me with ease is when I need to get worried. This is also the reason why I need to let go of the work that I’ve done and start something from scratch, and luckily as I work on something for many years the passage of time also necessitates a change in my state of being. Because over time I’m changing as a person. So for the new work, I just have to ease into my current state of being and find what I see in the world.

There are some photographers who I love, who have worked consistently with a single vision all their lives, and they’ve made the language that they use their own in that passage of time. But for the person that I am, I cannot afford to try and have authorship over any language over time because I don’t think I’m capable of surviving that repetition and this strong feeling within me of one’s photography being destroyed by being a photographer has provided me a life line. I have to try and just survive for as long as I can.

Who and what influences you and your photography?

They’re always changing. Right now it’s the short stories of Boris Vian and Saadat Hasan Manto.

Tell us about your work. What interests you as a photographer?

It’s a difficult question to answer (again!). You’ve asked something very broad and it’s always awkward for me to talk about my own work because it’s for others to see it and say what they feel about it. As a photographer everything interests me. Actually if I could, I would work in whatever medium I could, be it writing, film or whatever else, but I’m not very good at any of those things. As a photographer it’s important to me have something to say that comes from within. I think I let go of the idea of photographing “what the world is” many years ago and now it’s about “what the world is TO ME”. My opinion on the world is more important than ever to me because it helps me to bridge the gap between me and the world.

The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer (2013-ongoing) © Sohrab Hura

Can you tell us about your work The Song of Sparrows in a Hundred Days of Summer?

It’s something I started in the summer of 2013. I had started working on “Land of a thousand struggles” in 2005 where I was very influenced by the politics of the left in India and in my photos the issues were at the forefront. However, later in 2010, when I did the work “Pati” I didn’t want to bring in any issues, but instead make it more about the people and the place. I felt that issue-based work was confrontational and I did not want to turn away people who weren’t so interested in stories from rural India. The summer heat in Pati stayed with me because temperatures here can go up to 50 Degrees Celsius very often, and this heat is something that I could feel and the summer heat is something that is common to all of us irrespective of whether we’re in rural India, or the urban one.

So for me this was a way to maybe take the people who would see the photos a little closer to the village in the photos. The fact that the heat here is more extreme may help in making the feeling of it more palpable although as it is still work-in-progress, I have to wait and see if it really works. When I would be there it would get so hot that very often I wouldn’t be able to think straight, or to just be able to stay there for days with each day being as long as a year. I would have to blank my mind very often. It was in these twilight moments of the mind that I would end up seeing strange things within the reality that existed there. So the idea was to just be there, get my brain fried in the heat, photograph the place within the intangibility of the heat. There is still a lot of work to do. It’s only been a couple of years at it.

I’ve heard some critics of “Personal Photography” that say most of it are too self-indulgent. How would you respond?

I would actually agree with them. I feel the same on many occasions as well, and I also question my own work. I feel that sometimes photographing “the self” or “one’s family” actually puts this sort of unacknowledged pressure on the viewer to appreciate it. Even if the work is ordinary or even bad, one can’t easily say so and this allows the photographer of the work to remain within the bubble. I’m sure I’ve been in this bubble too at times. I think “personal photography” can be extremely powerful when it is really powerful and extremely shit when it is not powerful, and there is a very thick line separating them. There needs to be an added responsibility on those of us working in these realms to push our “personal photographs” beyond the idea of “personal photography” so that our photos are able to live as long a life as they can. We cannot afford to take them for granted simply because of where they’re from. Otherwise they’ll be nothing more than a gimmick which is what most of our works tend to become.

You mentioned “you have been outside an establishment for so long working on your own”. But you are quite a big part of the Angkor Photo Festival team and I believe the Delhi Photo Festival too right?

Yes, Angkor Photo Festival has been a family for a long time and it helps me to go there because of the energy there. For me, young photographers are very special because they have an untainted energy and a beautiful naivety that most of us lose in a few years, and it really is good for me to be around and amongst so many of them with that energy. Delhi Photo Festival is in my city, and I’m happy to help in whatever way that I can.

It’s not really that kind of an establishment that I was talking about, I was talking about working in isolation for the last 4 years or so, and not putting work out. Of course that doesn’t mean that I have to cut away from photographer friends or help ideas that I have faith in. The photo world has changed since I started. There are many more opportunities now than there were a few years ago. Life on the internet has completely changed as well where so many photographers are connected to one another and are able to view every new work that comes out on a daily basis. A new young star is found every few months or even weeks. It’s all good.

But for me it all started to get a bit scary as a young photographer. It wasn’t so much about the new opportunities as it became about a rat race. It wasn’t so much about being connected to other photographers and editors and curators and other photo people as it became about the need to make your presence alive in the deluge of information for as long as you could, even if it required you to spend more time updating things about yourself and doing other things than actually making work.

“When I look at the younger photographers today, there are some really exciting ones but most start to fade away quickly. The works feel kind of under-cooked and don’t stay with me that long.”

When I look at the older photographers who I love, and there are so many of them, I realise that most have worked like crazy for years, and gone through so much struggle even if it was involuntary. And it was only after decades of work that so many of them got recognition. But their work has been immortalised and these works will live with me forever. When I look at the younger photographers today, there are some really exciting ones but most start to fade away quickly. The works feel kind of under-cooked and don’t stay with me that long. And most importantly, I don’t feel jealous of anyone’s works as I do with the older photographers that I love.

The New World (2012). © Sohrab Hura

Maybe I’m wrong and I have a warped way of looking at things but I feel that it is extremely important to feel whatever little struggle that one can for as long as one can; even if one has to voluntarily create the conditions for it, because as one’s work gets better known, and as time passes, one tends to get a little bit more comfortable, and with that comfort the fire within one dies just a little more.

I believe that all of us are born with a beautiful way of looking at the world and then it is up to us to protect it or lose it. We don’t find something that didn’t exist, it was always there.

So to protect myself, I stepped out of this rat race of photography and it allowed me to work in a way that made me happy. In between, I started to hate photography but this cutting away from the system made me happy again. The system is about the mechanical way in which we photographers are streamlined into working. There is almost a set way in which we all wait and apply every year for the award dates, sometimes quite mindlessly. There is almost a systematic need to categorise yourself either as photojournalist/documentary photographer or one working towards the galleries. In this whole process sometimes we forget why we started photographing in the first place.

For me it was good to kind of disappear in this way. I know that a lot of people assumed that I did no work all this while, and that I had done whatever work there was in me to do, and that i was “lazy” but it was really good for me to be away from all these kinds of expectations, and not be a performer who was doing work to prove or validate something. And being away from the system allowed for it to just be me with the questions that were of concern to me. But more importantly, it allowed me to feel vulnerable and raw and lonely, which are the things that stoke the fire within me and make me hungrier than ever to make work.

I’m still young and have hardly done any work. And maybe whatever I feel doesn’t really make sense, and I’m actually set to fall flat on my face pretty soon because of all that I believe in. But I feel that I’m a much stronger person (and a photographer) today because of that decision and I hope to live just a little longer as a photographer because of it.

Name 3 most important people in your Photography and why.

I’ll name a few more than 3.

1. Swapan Parekh for being the first person to have shaken me out of a static way of looking at the world. He was the first person to have told me of the importance of finding one’s own language. He’s also one of the most underrated photographers there is.

2. Antoine D’Agata for asking me if I would live my life the way I was if I was not a photographer. At that time “Life is Elsewhere” was in its recent years and I had started to question myself whether if while working in a diaristic way I was consciously or unconsciously “performing” for the camera to make my life seem a way that would help the work, and if so, was that diaristic way really a diary at all. The seeds of doubt were sowed during this time and his question pushed me to question myself about the idea of honesty relentlessly for the nest 4-5 years.

3. Kosuke Okahara for being the photographer and the person he is. In this photo world he is like an older brother in many ways. A kind of a sounding board. He is also someone who is scarily principled, and he is an incredible benchmark to try and live up to.

4. Christian Caujolle to be able to have the most beautiful conversations with. There are many moments when I absolutely hate photography and when I listen to him I feel so lucky and privileged that I’m able to make photos. My soul would be half empty if it wasn’t for him.

5. Francoise Callier for being the first person to believe in me, as she did in so many others from our region who are all amazing photographers themselves. She is still in touch with so many new photographers, and for someone in that position there is nothing more special to have this unknown person encouraging you like your parent or grandparent would.

6. My mother for just being my mother.

Lastly and with a twist, what’s the worst piece of advice you can give a young photographer?

Don’t do it (for whatever reason).

Thanks Sohrab. Congratulations once again, and see you soon at Angkor!

Share

Comments 10

I believe , photography,like , any other art form , is a lone-journey:.. Mr Hura is having that journey with his unprecedented Insight & compassion . In fact it acts like a catharsis . A big thanks for infusing among us the Art of loving & for being with All those subalterns, who are often mute & missing languag.. Hope to see him reaching his zenit.

Pingback: Ten Indian Street Photographers Whose Work You Must Follow | Picsdream

Pingback: Part 2: Times And Tides In The World Of Photography | Invisible Photographer Asia (IPA)

Pingback: Sohrab Hura | Cada día un fotógrafo

Pingback: Sometimes you can destroy your photography by being a photographer | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA) | 亞洲隱形攝影師

Pingback: Getting Personal – 8 Photo Essays on Family in Asia | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA) | 亞洲隱形攝影師

Pingback: Sohrab Hura joins Magnum: “Life is Elsewhere” | JanNews Blog

Pingback: PJL: August 2014 (Part 1) | SanSer News

Thank you for the great interview. As someone who is just starting to find his way in photography I appreciate the insights and level of introspection Mr. Hura displays in his responses. It’s a lot to think about as I find my own way down this path.

Thanks. That was one of the most interesting photography interviews I have read in a long time.