© Zhang Xiao ‘Coastline’, n.2

If it is not for his name printed in big bold font on the exhibition panel, I would not have recognised it is Zhang Xiao’s work that is showing in the gallery. Zhang has abandoned his signature Chinese portraits and landscapes and entered a new arena of conceptual photography.

Walking through the gallery, none of the work is visually reminiscent of his acclaimed landscape series ‘Coastline’, which gives audience a glimpse of the fantastical China in the midst of rapid urbanisation. This time in ‘About My Hometown’, his third exhibition at Blindspot Gallery, he continued exploring the same motif, but zooming in to his family.

The emerging photographer is well known for his ability to catch people and object at the wrong state, producing surreal imagery. In ‘They’, Zhang showed secular Chongqing citizens at a moment of euphoric leisure. In ‘Coastline’, he travelled 18.000 kilometres along the Chinese coastline to photograph the surreal landscapes he encountered.

© Zhang Xiao ‘Coastline’ n.12

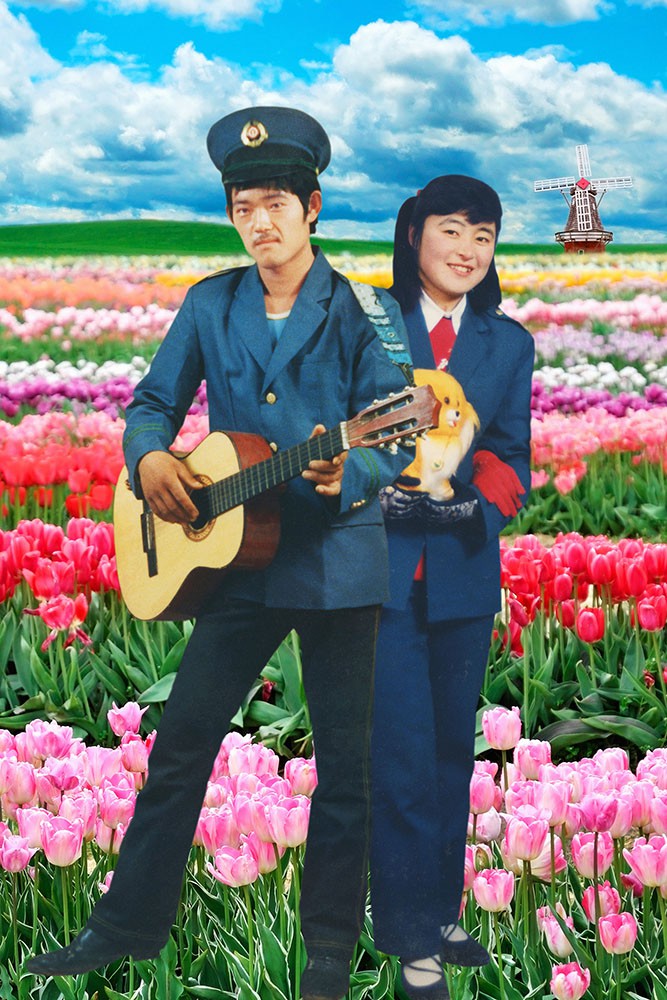

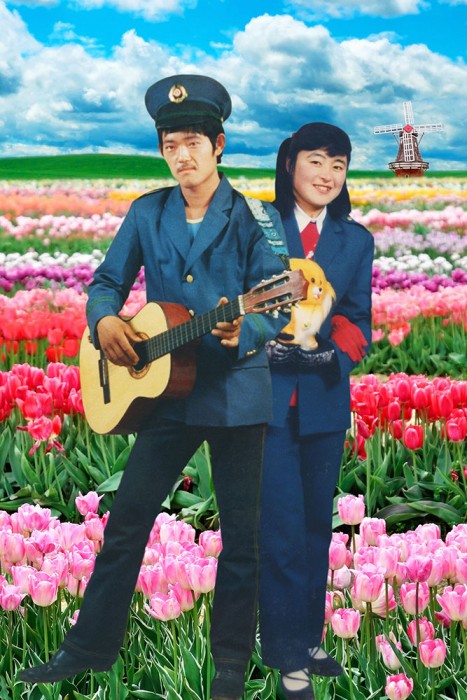

The photographer exhibited his recent projects, including ‘Eldest Sister’, ‘Relatives’ and ‘Living’, which showed the transition of the photojournalist-turned-artist’s approach towards photography. Just like his contemporary, he began exploring conceptual photography, putting down his Holga and making images without one. For ‘Eldest Sister’ and ‘Relatives’, Zhang scanned old studio portraits of his relatives and composite portraits of his eldest sister. He later printed them into mural-sized photographs, presenting a visual mockery of the cringe worthy results when consumerism-driven aesthetic meets clumsy digital photo editing techniques.

In ‘Living’, Zhang incorporates performance art into his photography, taking daily self-portraits with newspaper from his travelling city as a prove of his existence – a practice municipal government required for his mother and her fellow migrant workers to claim pension from authority at her hometown.

I suggest ditching any preconception of Zhang’s work before going to the show. In his latest exhibition, Zhang became an image curator, collecting images that illustrate an modern nostalgic relationship and ideological conflict between their rural birthplace and newly inhabited urban cities – a collective sentiment unique to urbanizing China.

Three Sisters Installation view at Blindspot Gallery.

What was your first camera? What was your first memory with photography?

After high school graduation, in the summer before university. I discovered a vintage 135 analog camera at home, which was a gift to my family, never used before. I fell in love with photography after toying with the camera for a while and began taking photos throughout my college years. I also have a cousin who open a photo studio, but he did not teach me anything about photography

I started in Shandong, taking pictures of landscapes, sunsets, trees and animals in my hometown. I kept doing that until the second year in college, at which I went online. I saw various works from peers and international photographers on forums. That opened my eyes to photography and its possibilities.

I know that you studied architecture in university. How did you became a photojournalist?

I became a hardcore photography fanboy. After my freshman year, I decided to work in the photo industry. I found a photojournalist job at a local newspaper (‘The Chongqing Morning Post). I was good for me, work was easy. I got to earn money and took pictures.

© Zhang Xiao, ‘Relatives’, n. 3.

© Zhang Xiao, ‘Relatives’, n. 4.

How is your general research process for your projects?

When I started photographing ‘They’ back in 2006, I did not have any solid theme. I photographed everyday for two years. The series was a result of editing and looking back at the two years of photographs. I do not start with a motif, I find one after shooting indiscriminately. I finished my series as I worked. Work was really easy, I finished after two minutes.

Your acclaimed series ‘They’ and ‘Coastline’ showed viewers a humoured side of the Chinese and a fantastical Chinese landscapes, as if it is seen through foreign eyes. Is China an eccentric place to you? Does China have its own reality?

Just like what you have said, China is absurd to me at times. I was a bystander the whole time shooting ‘They’ in Chongqing. Sometimes I think I am just another foreigner in the city. I had never been there. I did not know the place. My hometown (a village in Shandong) is the only place I know throughout my childhood and adolescence. When I arrived at Chongqing, I recorded whatever is surreal to me with my camera.

It is nonsensical. Sometimes, you walk on a road and something will appear in a wrong place or an unnatural state, but it continue to exist in a way that is incomprehensible. That is what I liked to photograph.

© Zhang Xiao ‘Coastline’ n.14.

How long did you prepare for the lengthy journey you embarked on to shoot ’Coastline’?

I thought about it for years. When I quit my job, I bought a camera and some film and went on a trip. I did not have much money. After half a year, I ran out of money and was looking for jobs again. I never thought I would win awards at the turmoil of my life. I won some grants and was elevated.

I stayed as a distanced observer on the 18,000 km of coastlines I travelled. I could go deep and stay a year for each place I had been, but that would take a decade to finish my project. I spent two days per location, ‘I shoot and go’. I could stay until the perfect moment and wait for the perfect shot but the projects would entail a different story.

In your latest projects, you turned your lens back on your family. What made you do so?

My two previous series can quite wholly portray the modern cityscapes of China. I do not see a reason to repeat what I have been doing. I was viewing the issue from a macroscopic scope – a ‘plane’, now I work from a point, going back to my hometown. I think it may give my audience a clearer vantage point to visualise the transition China is going through.

© Zhang Xiao, ‘Relatives’, n. 1.

‘Eldest sister’ is very different from your work, thematic-wise and aesthetic-wise. You edited the face of your sister on what seems to be cliche studio portraits. To me, I see a mockery on a prevalent Chinese photographic aesthetic. What is the idea behind the project?

Partially. I discovered some photos at my eldest sister’s house, composite portraits that she paid to get done by local photo studios. I scanned them and printed them out in mural sized prints. I have evolved from direct photography, I think that would be my exhibition more diverse, but I will continue to illuminate my idea through images.

Foreigners and people living in the urban area can immediately tell the portraits are poorly edited with kitsch colours. It is simply an eyesore. But to my sister who is a villager, the composites are perfectly done. There is a huge difference of aesthetic standards between city dwellers and villagers, both are supported by huge number of people. I would say the ‘villagers aesthetic’ followers slightly outnumbered the rest .Their living environment and experience determine their photographic aesthetics. The project opens a discourse on visual beauty. (Is this practice popular in the village) Yes, and considered very classy indeed. The technicians at the photo studios swap the face of my eldest sister with that of a model using computer softwares. (So everyone is fine with the result? even the technicians?) They all think it looked fine. These photos are their longing to a lifestyle, their longing to beauty, to fashion and to travel. Most villagers have not been to a prairie or even Beijing, so posing against a studio background of landscapes and famous monuments somehow console them.

How does Chinese first come into contact with photography?

Through photo studio. Many Chinese still do not own a camera. One of my vivid childhood memories is flipping through my family album and discovering family portraits of my sisters and cousins, all taken from the same photo studio, posing against the same background, even after decades.

Moving on, what is your plan?

I will continue to explore this motif: hometown and may include installation work in the future.

Which photographers inspire you?

There are too many, I cannot tell. Master photographers and peers both have combined influence to my work. They are all important sources of inspiration.

I liked Diana Arbus and documentary photography when I was in high school. I still love her work but not as passionately. Different photographers inspire me in different stages of my career.

More from Zhang Xiao on http://www.zhangxiaophoto.com

Interview by Sheung Yiu originally published on urbanautica.com.

Share