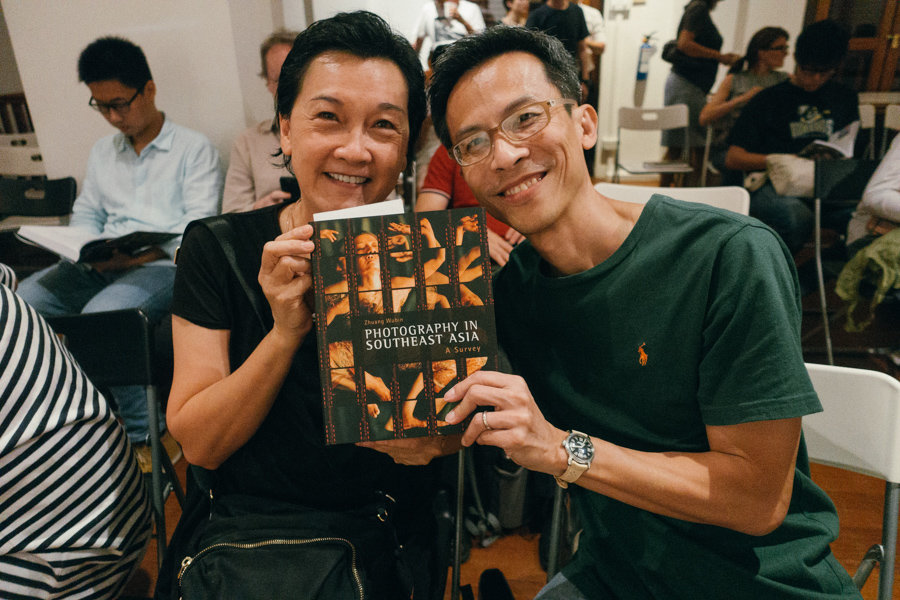

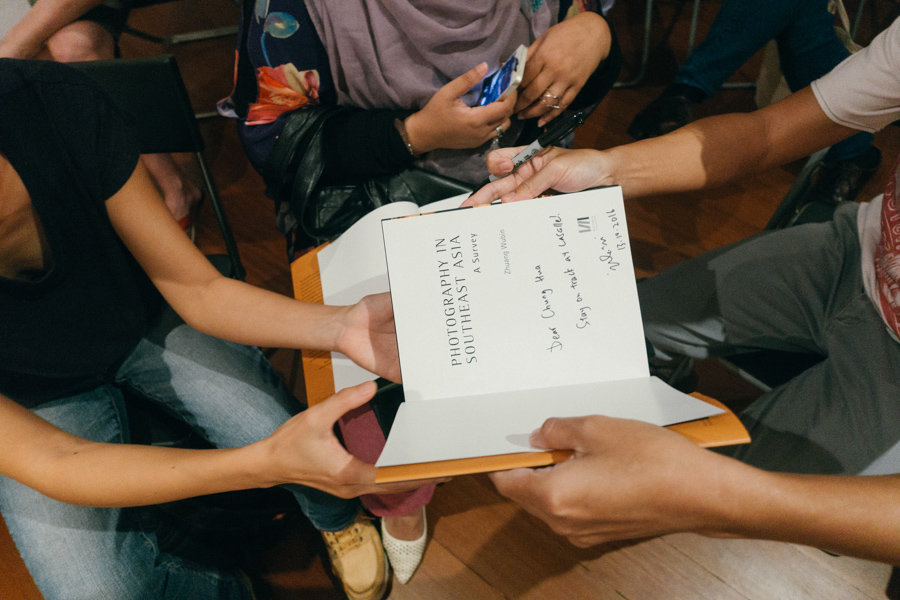

Zhuang Wubin’s Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey was launched at Objectifs – Centre for Photography and Film on 13th October, 2016. Wubin’s survey begins in the colonial era, at the point when the transfer of photographic technology occurred between visiting practitioners and local photographers. With individual chapters dedicated to the countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, The Philippines and Vietnam, Photography in Southeast is a comprehensive attempt to map the emergence and trajectories of photographic practices in Southeast Asia.

The launch featured a dialogue between Zhuang Wubin and special guest Chia Aik Beng on the influence of social media on photography and a Q&A with the audience on the survey. Here are some highlights.

Wubin: How did the Instagram movement help your career?

Aik Beng: I came into photography quite late (2010) when everything was already done on the phone. Since day one, Instagram allowed me to share my work as a personal photo journal, diary and scrapbook. I found out that a lot of my work was being discovered and distributed through Instagram, including the senior editors at Washington Post and the New York Times, and not so much through Facebook and Flickr.

Wubin: Why do you say you are not a photographer? Are Instagramers not photographers?

Aik Beng: I’m not a photographer because I just love to record everyday stuff. I’m having a lot of fun and I enjoy what I do and what I see. I’m basically recording my time here and the time being given to me. I do not start with a project in mind. It’s only after I look at what I’ve captured that things come into play.

Wubin: You have a website and a Facebook account, Do you think they do the same thing or play different functions to your career?

Aik Beng: They are different. For certain personal projects, I will share it on my website. For my daily junk, I will share it on Instagram. I draw the line on what I would share.

Wubin: There are some who commented that without an Instagram account, you don’t exist in the photography world. Do you agree?

Aik Beng: No. A lot of people think that Instagram is a good platform to showcase their work. I’ve been approached and asked whether they should show their portfolio on Instagram. I told them Instagram is a social media platform, it is not a photo gallery or website. If I’m on a project, I will share some images, to tease people and then direct them to my website. This is how I distribute information.

Wubin: The other criticism is that due to Instagram’s popularity, a lot of people try to mimic styles like faded colors. What is your opinion?

Aik Beng: It’s a fad. Instagram appeals to the young generation and some do follow trends. For example rooftopping, a practice of accessing rooftops to take dizzying skyline photography where one’s shoes are seen. Soon shoe brands started approaching the practitioners.

Wubin: What is the impact of Instagram on photography in Singapore?

Aik Beng: This is a tough one. You cannot ignore Instagram’s popularity. Magnum and many prominent photo organisations are already using it. It really depends on what the individual wants to show. I choose to show Singapore while some prefer to show selfies, food etc.

Wubin: A large part of your practice is the sharing of your photographs. Is that why you are a big Instagram supporter?

Aik Beng: I won’t say I’m a big supporter. I use the app to distribute my work. I got into photography during the modern era when social media is the way to go. I’m unlike you guys, pioneers who do not have the luxury (Audience laughs). In fact, I once got so carried away with social media that my mentor, Kevin WY Lee, told me to slow down. In the past I over share. Now I’m comfortable with sharing just one or two images daily. You learn along the way.

Q&A With Audience

Is photography in Southeast Asia male dominated?

Wubin: I have a way of explaining this. For example, in photojournalism, conventional wisdom seems to say it is the right answer. There tends to be more male practitioners in photojournalism. But if you frame it as people doing selfies or self portraitures on Instagram, and I don’t mean it in a negative way, there will be more female practitioners. It all depends on how you frame it. One of the main ideas of the book is to emphasise how we have to be careful in framing the question. I want to intervene with the way photography is written. Most of the art writing today where photography surfaces, vernacular and street photography are often excluded.

How do you define each genre?

Wubin: Even though this is a survey, it doesn’t cover all genres of photography. For example, food photography is excluded. The nature of publishing a book is already an exclusion process so that you can include the content you want. I won’t totally disagree if you were to say this is an elitist way of framing. I try not to think too much of the genre. The genre restricts our understanding of photography. We end up discussing the labels and not the work.

I wonder if you see digital, i.e, the sharing via social media, changing the formation of the national visual context? Secondly, Aik Beng, while you said you are not a photographer, you are developing and pushing certain visual styles through the sharing process. I’m interested to learn more.

Aik Beng: It’s up to the individual when they wish to embrace it. Things are changing and one should not get too hung up. Instagram will go one day as well.

Wubin: I’ve answered that in the afterword of the book. The book is organised according to nations. If you use that framing, it would seem like there is a different kind of photography in each country, i.e., Indonesia has a certain kind of photography. But this is far from the truth. What we are experiencing today, the accelerated sharing of visual images across borders, is not new. Photography from the very onset has been conceived as an international medium. To take a simple example, salon photography which peaked in the fifties, was thought of as an international practice. If you look at their catalogs, they accepted submissions from all across the world. They see themselves as a regional or international grouping of photographers. It’s not restricted by the idea of nations.

How do you go about choosing the photographers you featured? And do you have any afterthoughts after writing the book?

Wubin: At the end of the book, I realized it’s impossible to do the book without leaving out certain things. The scope of the region is too big and my disclaimer is that we cannot cover everything. There remains a lot of work that can be done. I’ve started looking at material in Sabah without a clear objective of doing anything yet. I started ten years ago interviewing artists and photographers. I naively thought there was little research available and I should do something by publishing the interviews. The Prince Claus grant in 2010 enabled me to do literature review. At that point I realised that the book was a possibility. By then, it was already six years into the process. The literature review revealed that research in colonial photography has been fairly well documented as well as the missing elements. I then develop the structure for each chapter. In certain chapters, chronological (Malaysia), and in others regional (Indonesia).

How do you think the modern way of sharing photography changes the way we tell stories?

Wubin: I would say that on a broad level, with the digitisation of photography, a lot more people have the opportunity to present their views. But that is still subjected to the web and what kind of images surface. Obviously we don’t see every image so there is still a control and moderation process.

Aik Beng: Hashtags are very popular now. It plays an important role in terms of how people want to see what they want. At the end of the day, it’s how you want to share the message across. It also depends on the viewers on what they want to see.

What are some of the highlights in the Singapore chapter?

Wubin: This sounds like a trap, but I would like to know the institutional stand, that is, what is the status of photography as an art form. Because we operate in Singapore and our medium is English, and we tend to believe we are in the middle of Southeast Asia. I’ve lived outside of Singapore for a long time and by shifting your perspective, the world is very different. We have to be very careful to assume everyone speaks English and all the cultural practices are formed through English. In Thailand, for example, a lot of information and discussions are in Thai. Likewise, a lot of Singapore’s photographic practices in the fifties were conducted in Mandarin.

Would there be different takeaways for different groups of readers?

Wubin: I definitely hope so. I didn’t write the book only to serve a certain group of people. I hope it would be useful for different kinds of practitioners, not just photographers but researchers, writers and anyone interested in the history of photography.

Aik Beng focuses on the everyday. But there’s nothing really dramatic going on in Singapore so it’s very hard for photographers not to end up like Aik Beng (Audience laughs). The everyday is a great discourse but there’s no disasters here. Does it mean it’s much harder to be a photographer here?

Wubin: No. When I was in Philippines and hanging out with a photojournalist, he shared that there’s nothing to photograph in Philippines and he wants to go to Russia. I wonder if I do a survey in Russia, would there be similar sentiments. The surfacing of the sentiment elsewhere might suggest a psychological perspective. Of course, if the subject is natural disasters, Philippines and Indonesia are better places. But photography is not just about that. There’s always interesting work to be done.

When I graduated a decade ago, the documentary photography scene was different. If Kay Chin or Darren were here, they can tell you the same thing. It was much more quieter. A lot more has surfaced since then. So if there’s a boom in photography practices then we should reconsider the assumption that Singapore is quite boring and there’s nothing to photograph.

Which Southeast Asian country are you most sympathetic to? If you could only write about one…

Wubin: Every country presents different challenges. I enjoyed writing about Malaysia and Philippines but they are different in terms of the scope and what I have access to.

How do you pick the people in your book?

Wubin: This is a survey that places a premium on being comprehensive. We also understand it is not possible to be comprehensive. I noticed that we tend to ignore popular photography but popular photography influences all kinds of photography. The main focus remains art and documentary photography. Of course, I’m using these labels as ways of organising my ideas rather than ranking their respective importance. I try to make it as comprehensive as possible in a limited survey which explains the presence of Lee Wen and Amanda Heng in Singapore’s survey. However, there are also practitioners who we think of as performance artists who use photography that are excluded.

Do you judge by the work or the person?

Wubin: Multiple. It also reflects upon the period of time and who is doing what.

What are your ideas of the originality of ideas? Who started the various movements in photography especially in the Southeast Asia context? Are we merely followers of trends as we are young nations?

Wubin: I wouldn’t assume we are the followers of trends especially at this stage. It’s easy to make a comment but hard to measure and provide evidence. We are in a situation where a lot of people are taking photographs but I always ask myself – do you think everything has been photographed? Furthermore, photography cuts into everything. It can be an advertising or political campaign poster image or even an art work. We are talking about photography in multiple context.

For countries that are much more open to the West, you can see the impact of conceptualism and the politics of the West. In the fifties, you can see the growth of salon photography throughout Malaya, Indonesia and Thailand. If you cut it across periods, yes.

What surprises you the most?

Wubin: I’m still here. I’m still alive at the launch. (Audience laughs)

~::~::~

Transcription (edited for length & clarity) by Sebastian Song.

~::~::~

Order the book now on the NUS Press Bookstore.

Published by NUS Press, Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey, By Zhuang Wubin was launched on Thursday 13th October at Objectifs Centre for Photography & Film, Singapore.

PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTHEAST ASIA: A SURVEY

AUTHOR: ZHUANG WUBIN

PUBLICATION YEAR: 2016

PUBLISHER: NUS PRESS

524 PAGES, 235MM X 187MM

ISBN: 978-981-4722-12-4 CASEBOUND

212 PHOTOGRAPHS

PUBLISHER’S BLURB

Photography in Southeast Asia: A Survey is a comprehensive attempt to map the emergence and trajectories of photographic practices in Southeast Asia. The narrative begins in the colonial era, at the point when the transfer of photographic technology occurred between visiting practitioners and local photographers. With individual chapters dedicated to the countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, The Philippines and Vietnam, the bulk of the book spans the post-WWII era to the contemporary, focusing on practitioners who operate with agency and autonomy. The relationship between art and photography, which has been defined very narrowly over the decades, is re-examined in the process. Photography also offers an entry point into the cultural and social practices of the region, and a prism into the personal desires and creative decisions of its practitioners.

Zhuang Wubin is a writer, curator and artist. As a writer, Zhuang focuses on the photographic practices in Southeast Asia. A 2010 recipient of the research grant from Prince Claus Fund (Amsterdam), Zhuang is an editorial board member of Trans-Asia Photography Review, a journal published by the Hampshire College and the University of Michigan Scholarly Publication Office.

Share