The 2nd Women in Photography Exhibition, co-curated and co-presented by Objectifs and Magnum Foundation, opened on 19th October. Four of the 18 featured photographers shared their work and aspirations in a talk the evening after. The following are some highlights.

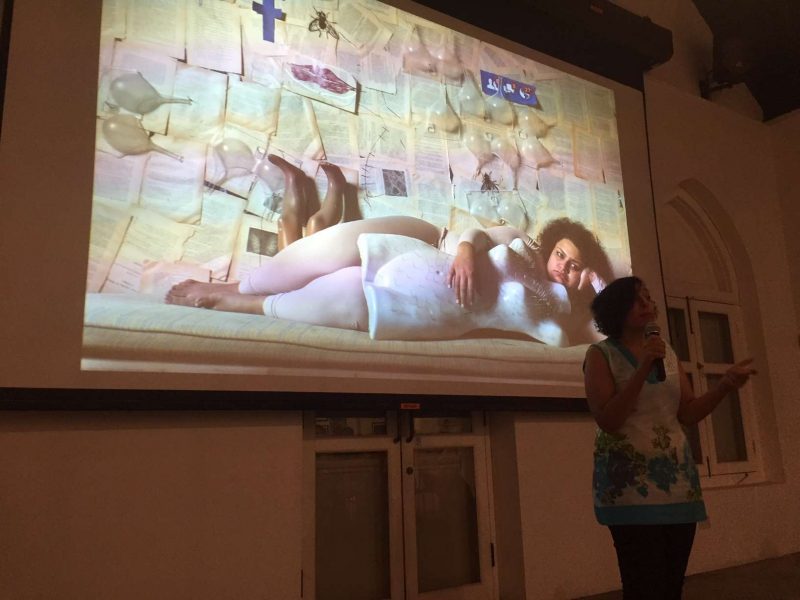

Homemade by Heba Khalifa (Egypt)

You can’t talk like that because you’re a girl.

“It’s a big burden on our lives. I mean not just in Egypt, everywhere. Women would guard her body. It’s exhausting. Sometimes I dream I leave my body and go. For doing these images, I created a Facebook group to see what it means to be a girl. What it means to have a body. We meet one by one at my place and we start to talk from heart to heart.I write from the stories I heard and I start to dream of photos, how to visualize these feelings.” Heba Khalifa

Our Limbo by Natalie Naccachie (UK/Lebanon)

How was I going to make people care again?

“The Syrian crisis happened when I moved to Beirut. One in four people in Lebanon were refugees. I started getting assignments to document the refugee situation. I felt I was taking the same pictures over and over again for four years. I grew frustrated. I felt no one care anymore and there was a fatigue about the situation.

I wanted people to feel what it was like to leave their home. I found Tania who was raised in Damacus and through her, I met with her friends. They all grew up in Damacus, went to university in Beirut and planned to go back to Syria. It wasn’t possible with the civil war and they had to go different places. They were spread around Qatar, Dubai, London, New York and Beirut. They come from middle and upper social economic background. They never felt they had the audacity to complain not being able to go back home because they had a roof over their heads and food to eat.

I created a journal to piece together everyone’s stories. I used their Instagram posts where they post about home. I actively photograph them and sometimes I give them a page to do whatever they wanted. These were pages where they got to express themselves.” Natalie Naccachie

[Note: I spoke to Natalie after the presentation about publishing her journal, a beautiful and meaningful work that should be circulated widely. She remarked difficulty in finding a suitable publisher and I suggested crowdsourcing instead.]

Mono by Xyza Cruz Bacani (Philippines)

Instead of asking questions, I chose to photograph.

“I was a domestic worker in Hong Kong for ten years. I started photography in 2009. I transited from street to documentary photography in 2014. I’m showing you my latest work, a collection of love photos, something cute for the night, since 2013. I’m always interested in the things I don’t understand. I don’t understand love (and) romance. I don’t understand politics and religion. When you are doing public displays of affection, you are actually isolated from the society but with someone else.” Xyza Cruz Bacani

Dying to Breathe by Sim Chi Yin

How are we going to go forward? Who’s going to bankroll this?

“I felt I was a photographer and I wanted to do long-form work. I was after this sense of social meaning and social purpose in life. I decided I had to quit and throw away my cushy life at Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) if I was serious about my photography. It was about working at different level because working for a national and regional paper, you want to test yourself in an international space. So that’s what I did.

I was extremely fortunate to befriend Susan Meiselas, who created the Human Rights Scholarship. I became the first fellow in 2010. It really opened a lot of doors and was career changing, for me and many other people, including Xyza.

This is a competitive industry but we like to pay it forward. What Susan did for me in 2010, I did for Xyza in 2014. I told her about the scholarship. I made sure she applied and made a strong case for her nomination. And off she went to New York.

The other aspect of Magnum Foundation is that it funds under reported stories around the world. I want to take this opportunity to ask all individuals to reflect on the value we put on journalism and documentary work. Today we get our news for free but someone still has to pay for the reportage. Someone has to be that conduit and quite often at great risk and sacrifice. I’ve been thinking about this long and hard. How do we pay for this? It has fallen on foundations like Magnum Foundation. The project, Dying to Breathe, was funded by two grants from the Pulitzer Centre and the rest of it was basically “own time, own pocket and own tears”. I spent four years from research to product, it is essentially a portrait of China’s leading occupational disease, black lung disease or pneumoconiosis. A conservative estimate of the number of people in China with this disease is six million. And if you think about it, that is the population of Singapore in absolute numbers.

The thing that made me do this project was that it was very under reported when I started and I was very angry that this was a preventable disease. When I started, people told me it was a terminal disease and I slowly realise it was terminal only for the poor. The men I photographed, you can see their portraits in the grey space, they don’t have that choice to seek treatment to prolong their lives. A lung transplant just wasn’t on the cards.” Sim Chi Yin

Q&A with Audience

I’M CONCERNED ABOUT LABELS AND THEIR DANGERS. DO YOU WANT TO BE KNOWN AS A WOMAN PHOTOGRAPHER AND HOW YOUR WORK ALWAYS STARTS WITH FAMILY, HOME, SELF AND BODY?

Emmeline (Objectifs Director): “Before I hand over the mic, for us at Objectifs, this is the second year of Women in Photography. First and foremost, it is about good photography. The labels are what we choose to put on things. When we choose what to go in, it’s always about what is important and impactful. If you ignore those labels and look at the work, it doesn’t matter who is behind the camera. That said, there are works that because of your gender, allows access. For example, Krisanne Johnson’s I Love You Real Fast which one would argue that as a male photographer, you probably will not get that kind of access.”

Heba: “Define what a male does. In art, a lot of men photograph naked women too. It is about exhibition. I exhibit myself, exhibiting issues that matter to me. If you have just one day a week, and you don’t have the passion for it, you will never make any project. I work six days, I have just one day and I take time to make the project. It’s not because I’m a woman but because it concerns me.

Natalie: “I’ve never put a label on myself. I’ve never restricted myself to do certain stories because I’m a woman. For my story, there is no way I could get into the bedrooms of these girls if I’m a guy. I just do stories I care about.”

Xyza: “For me, photography is a verb, there is no gender. I get where you are coming from. I even ask when we will have a show that is titled ‘Men in Photography’. Why is it everytime there is a show about women, there is a title women in photography. Being a woman in the photography world is much harder than being a man. We need to work twice as hard just to get half the credit. People don’t take me seriously in street photography partly because I’m a woman. I enjoy street photography and I have access to things that men don’t. For example, I have access to domestic workers everywhere. I then realise I don’t have access to the male migrant homes. (Audience laughs) I tried to be a male but I was too pretty. Gender is not important but we need to embrace who we are.”

Chi Yin: “I’m a bit color and gender blind. I really think it’s about what’s inside and what you are interested in. I had colleagues in China who’d come to me and say, “I really envy you and because you are a woman, you have access to these people.” I don’t think I would have the access if I was a man. But there are also stories that are sensitive and delicate that are shot by men.

But we are under-represented in the world and in Asia. It is much harder to be a woman photographer physically in terms of how society views you. I’m a young-looking woman working in China where sexism and ageism are built in. Very often, I would go to events and these uncles with their heavy equipment would come up to me and question my professionalism. I would just make the pictures and leave. I do not need to engage with such people. Those are things we deal with on a day-to-day basis.

As a woman, it was more difficult to photograph the project. If I were a man, I could go into the gold mines anytime. As a woman, I was seen as dirty and I had to pretend to be the lunch delivery girl. We, the sister-in-law and I, were walking around in shin high waters for two hours, completely lost and without phone signal and GPS. I had to go in to get the footage to explain to people the source of the disease. It was impossible for an urban Chinese to understand.”

NATALIE, WE ARE SEEING A DOMINANT REFUGEE NARRATIVE BUT YOUR WORK SHOWS A VERY DIFFERENT STORY. HOW HAS IT BEEN TRYING TO GET THE STORY OUT?

Natalie: “When I started doing it as part of the Arab Documentary Photography Program, I told people and they were all very interested. It got a few minutes on CNN and our exhibition has been to Italy, Amsterdam, Saudi Arabia and Beirut. The response was emotional when people came very close to the pages (which were printed the same size as the diary). I wanted people to feel what the girls felt.”

HOW DO YOU DEAL WITH THE VULNERABILITIES, MENTALLY AND FINANCIALLY, AS A FULL TIME CREATIVE?

Xyza: “During the past few days, I have been interviewing a lot of people and I was really tired. I think that’s the difficult part. The second part is financial. Photography is a part of me but it’s what I do now. If there’s a time when I cannot sustain my basic needs of life, I’m going to find another job. But I’ll still photograph. Seriously, the pay is s*** but it’s about the passion.”

Heba: “I work as a photojournalist. It is hell. They give you assignments and they want you to deliver immediately. They don’t want you to dig. With this work, I spent two years thinking, writing and seeing people in my house. Nobody wants and pays for this work. This project is for myself.”

Natalie: “When I do a story, I try to invest myself 100%. I’ll be with them, trying to build trust so that I can be in their space and document how they are feeling. Financially, the pay isn’t amazing. When you do a story, you have no guarantee a magazine or publication or gallery is going to take it. It’s a risk.”

Chi Yin: “I think being both a creative professional and being freelance comes with lots of emotional, financial and physical risks. You don’t do this if you are out to make money. You do it because you have a passion for the craft or you have a social purpose.

Why don’t you get a real job is something we hear a lot. (All four photographers nodded) My parents are in the audience and I’m sure they think that every morning when they wake up and see me doodling away on my computer or disappearing or attending talks like this. (Audience laughs) I had a pretty good job which I put away. Financially, I’m not sure it is viable anymore just to do editorial work. Some of us teach. Some of us do some commercial work. Some of us sell prints. Some of us make pictures of babies and pets and weddings. We basically stride along just to stay afloat and to do this other work we feel is important.

I urge everyone to think what is the way forward and how are we going to pay for the stuff we continually want to see. How do we pay for the guy who put his life on the line to go to Syria? There are a bunch of photojournalists out in Mosul as we speak, getting pictures from the frontline.”

WHEN YOU DO SOCIAL JUSTICE PHOTOGRAPHY, HOW DO YOU STRIKE THE BALANCE BETWEEN DOCUMENTING AND THE NEED TO INTERVENE?

Chi Yin: “I get asked that quite a lot. The easiest way of answering is to say that I’m not pretending to be objective. I don’t describe myself as a photojournalist these days, I’m a documentary photographer. I’m not shy about having a point of view. I try to be fair but I can’t be objective. You have to feel angry or upset about something to have that passion to go at it for a few years. It is fine as long as you are honest about your process and intentions. I’ve often said on this story that I’m a human being first and a journalist second. So when he needed help, I intervened. I did what was humanly possible and this was the outcome.”

Xyza: “Jolovan and I are working on a project. Before I start my documentary project (which I call personal projects), I should care. If I care, I cannot be objective anymore. I always say that to myself. I’m not a news reporter. If you can do something for these people then do it. A lot of people say I represent migrant workers because I was one. But I’m lucky, the one in a million, and in my photography, I magnify their voices. When I did this story about human trafficking in New York. There was this subject who had not seen her children for seven years. As a photographer, I’ve met a lot of people who can do something about her case. When I photographed her case, she was applying for a parole to go home to see her children. She was denied a lot of times but I was preaching her case in the background to the people I know. I try to intervene because I care about the issue and the project.I don’t know if it’s right or wrong but that’s how I do it.”

~::~::~

Transcription (edited for length & clarity) by Sebastian Song.

~::~::~

About Women in Film & Photography

The annual Women in Film & Photography Showcase at Objectifs is a tribute to the artists, photographers and filmmakers who have created works that tell stories with impact, break boundaries and inspire us. In this 2nd edition of Women in Photography, documentary works by 18 women photographers take centre stage. Co-presented with the Magnum Foundation, photographers originating from Egypt to Singapore have worked in difficult circumstances to document the lives of the disenfranchised and marginalised. From works that reveal intimate domestic struggles, to observations of communities, to universal stories of humanity and empathy, these stories reflect the diversity and complexity of the issues and themes explored by women photographers in recent years. The featured women photographers are associated with the Magnum Foundation, having been recipients of the foundation’s Emergency Fund, Human Rights Fellowship or Arab Documentary Photography Program. Established by the renowned Magnum Photos, the foundation champions in-depth, independent documentary photography that fosters empathy, engagement, and positive social change. Women in Photography is held in conjunction with Women in Film, more information here.

Share