Portrait of Ismail Hashim. Image courtesy of Puah Chin Kok

UNPACK-REPACK: Archiving & Staging Malaysian Photographer Ismail Hashim

An interview with curator/archivist Wong Hoy Cheong

We are here to witness, or so we believe. But few have witnessed the way Malaysian photographer Ismail Hashim (1940- 2013) had. We look at ten thousand things and move on after discovering they cry out to us nothing. Ismail, on the other hand, lived and died obsessed with finding their meaning to the world.

A photographer, graphic artist, art teacher and activist tucked away in an idle part of Penang, Ismail is one of Malaysia’s most celebrated photographers whose images have captured the imagination of all layers of society.

In his career which spanned more than 50 years, Ismail has stubbornly refused to take readily available images before his eyes at face value choosing rather to deconstruct and reconstruct them repeatedly. He would take a photograph, slice it into six pieces and put them together again.

He painstakingly took photographs of postboxes, worn-out bicycle seats and workers sitting on bicycles only to have them cropped, reprinted and montaged over and over again as though to decode the secret messages behind them.

How much he discovered has remained a mystery. They vanished with him when he died from a motorcycle accident in the afternoon of June 23, 2013. His last photograph had been taken that day- it was of a toilet bowl.

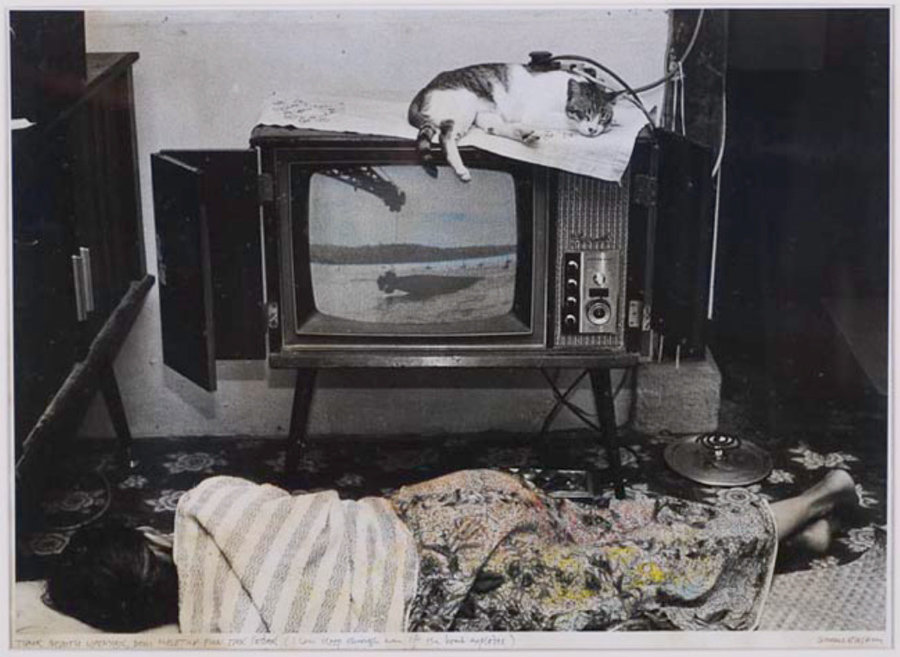

He might have done so out of sheer mischief. Ismail was known to be cheeky. The captions of his photographs tell us so. They also tell us that the meanings in a photograph shift through text. That there is an alternative way to look at a photograph that is, to see beyond what is visually dominant. To hunt for the underdog detail in a photograph. And make sense of it.

But, where and how does one begin to make sense of Ismail Hashim?

Wong Hoy Cheong, the curator of the late Ismail Hashim’s UNPACK- REPACK: Archiving & Staging Ismail Hashim (1940-2013) which will open at the National VIsual Arts Gallery, Kuala Lumpur this March 13.

In December 2013, Wong Hoy Cheong, a prominent Malaysian visual artist, archivist and writer set out on a journey with this question in mind when he first entered Ismail’s home in Penang to collect his works, rolls of undeveloped film and personal belongings.

Six months later, Ismail’s posthumous solo exhibition called “UNPACK-REPACK: A Tribute to Ismail Hashim” which Hoy Cheong curated was shown to the public at The Whiteaways Arcade in Penang.

Come this March 13, the exhibition will be “re-packed” to the National Visual Arts Gallery, Kuala Lumpur with expanded insights into the photographer’s works.

UNPACK-REPACK: Archiving & Staging Ismail Hashim (1940-2013) is a hybrid exhibition using 2,000 prints, negatives, hand-written notes and books belonging to the late photographer to probe the layers of his career retrospectively.

“What I want to do is to piece out the different strands within this human being, within this artist, this historical and political person and romantic person and hopefully, allow the public to find their own understanding and entry point to him,” he said.

All in all, Hoy Cheong has amassed more than 20,000 objects from Ismail’s home to be archived and documented.

Tidur Punya Ralit, Bom Meletup Pun Tak Sedar (Image courtesy of the Ismail Hashim’s Estate)

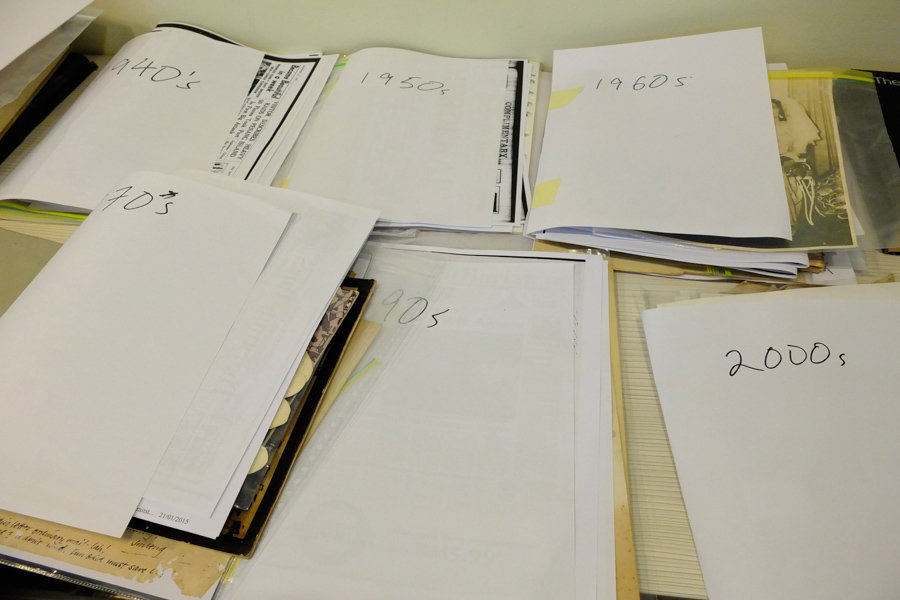

At the Fergana Art in Kuala Lumpur, where Hoy Cheong has been working as adviser, curator and archivist on Ismail’s works for more than a year, Ismail’s work is in every corner of the gallery. His handwritten notes on numerology, newspaper clippings on the country’s politics he kept, and poems by Emily Dickinson he meticulously wrote and re-wrote on notebooks are now compiled and filed according to year.

More than about Ismail’s photography, the exhibition aims to open up a discourse on the primary archiving of his works, a practice that has yet to gain importance in this region. Hoy Cheong is planning a section that allows the public to find and examine all archives of Ismail’s works and personal belongings.

We recently sat down with Hoy Cheong who spoke candidly about his curatorial decisions and challenges in interpreting Ismail’s works juxtaposed against the historical events in his life. The question-and-answer session is edited for clarity and length.

IPA: The UNPACK-REPACK exhibition was first opened in Penang, Ismail’s hometown, in June 2014, mainly as a tribute to him. What can we expect from this upcoming exhibition in Kuala Lumpur?

Wong: The first exhibition in Penang consisted mainly typologies and classifications.

At that point, we had to fight against time because we wanted to launch the exhibition on the anniversary of his passing.

The KL show will consist of part of the Penang show, as well as details and information to locate Ismail spatially in an environment and his community. In a way, I am trying to understand Ismail and his personality, his works, his state of mind, his location within the community and history and put that together as some of kind of visual representation.

You can call it an installation. An exhibition is an installation. A curator’s role, which also comes from the word “cura” is to cure, to heal. So, my role is also to heal the state of archives for public consumption. But I also want to bring out this message of the incompleteness of archiving. And it is important that an archive is never completed because you do not want to sap its meaning.

IPA: In curating Ismail’s work, you have set out on a journey to tell the world what his works and life is about. In your opinion, what has set him apart from other photographers?

Wong: As a curator, the first thing I need to know is what in the world interested him visually, which are people, environment and people working.

Some people hate his works, especially trained photographers who claimed he was not a good photographer because he had no qualms in just shooting, cutting the part out and composing it again via reprinting in his darkroom.

But he is a clever photographer. He has an eye for something which is lost within something else. He is constantly constructing and deconstructing meaning. For example, why would he slice a photograph into six sections, put them back together and why did he not cut it up straight? I still have no answers to it but as I go through his works again and again, I am beginning to understand where he got his impulses from.

In his titles, he uses verbs and verbs are references, words of action. For instance, his work entitled “Fern and Fun” makes a reference beyond the title and the title helps you to understand that he refers to something beyond the visually dominant. The fern is so visually dominant but the word ‘karaoke’ is in a tiny spot in that photograph.

What I think is so potent about Ismail Hashim is the notions of the referent. It is always in reference to something else that is beyond what is visual whether it is a reference to absence, human presence, mortality or visual splendour.

IPA: Tell us more about the archiving process in this exhibition.

Wong: In December 2013, we went to his house and studio with the permission of his family to pack up his stuff. We have at least 19,000- 20,000 items. These items include his own test prints, finished works, commercial prints, negatives, slides, documents, books, art paraphernalia.

We have documented about 14,000 objects and documents. We are re-framing some of his works. Those items that need to be archived are put into archival boxes, slides are labeled and digitised so we now know which box contains what. But we haven’t started digitising every slide yet, which is another herculean task.

We will exhibit about 2,000 items and make these available for the public in the exhibition in a section called “The Living Archive”. There, we will construct shelves in the gallery, set up tables, lights and computers so that people can do research on him. We will also look at our own archiving process and the weakness of our own archiving process.

The late Ismail Hashim’s handwritten notes on numerology, newspaper clippings on the country’s politics he kept, and poems by Emily Dickinson he meticulously wrote and re-wrote on notebooks are now compiled and filed according to year.

I want to lay open the complexities of archiving and lay open our own inadequacies and that an archive is never finished. French philosopher Jacques Derrida said the moment you finish archiving or you close an archival system, it becomes totalitarian. An archive should be constantly opened to new interpretations and creation of new archives.

In this section, I also hope that we make it clear that photography equals archive. A photograph is an archival document. If you look at photography, meanings change over time because photography is only located within time. The moment it is removed from context, its meaning shifts.

For instance, a lot of people talked about Ismail capturing a disappearing past. But he never captured the disappearing past. He captured a very potent present but because the meaning shifted, we think of it as nostalgia. Actually, it is not. When he shot people riding on bicycles, they were workers at that time. It was a potent a present as it could be. But now, we look back and see it as a disappearing past.

Post Boxes along Bagan Serai – Taiping Road (Image courtesy of the Ismail Hashim’s Estate)

IPA: You are primarily a visual artist and writer. What have you learnt about archiving the works of an artist from this huge project?

Wong: When you work or start working on an archive, you have no idea where things are, how things are contextualised and what all these things you collected mean. So, it took us a while to figure out the kind of terrain just to understand Ismail, the things he focused on, what occupied his mind, what he liked to see, what kind of notes he took, what kinds of poems he read.

We realise that we are the pioneers in primary archiving in the arts. Archiving has not been dominant in this region. We have tried to keep as closely possible to international archiving standards but it is not sustainable for us financially because we are not a museum nor an archival centre. We are trying to find alternative materials for storing archives so that we don’t have to import them.

We made a lot of mistakes along the way, like, packing up Ismail’s belongings in his home without considering why he had placed them there. So, some of the context is now lost.

Because of Ismail Hashim and speaking to my own contacts with other people in this region, I have realised that in the past five to 10 years, visual arts archiving has certainly become more important. In the past 10 to 15 years, a lot of the senior artists born prior to Second World War are dying. And so, the urgency for archiving has started to appear.

This is because archive is power. To understand an archive is to have a power to transform. Jacques Derrida who wrote “Archive Fever” said it is almost a death instinct- the need to archive and the need to destroy archive. It is something we need to deal with because the erasure of archives is constantly happening in the world. The burning of books and destruction of monuments, for instance.

IPA: As a longtime friend of Ismail’s, do you find it exceptionally challenging to be objective in curating his works?

Wong: I don’t think there is such a thing as objectivity. An archive is never neutral. A curator is never neutral. There is always a point of view. I have no agenda to instrumentalise him for my own good.

What I want to do is to piece out the different strands within this human being, within this artist, within this historical and political person and romantic person and hopefully, allow the public to find their own understanding and entry point to him.

Interview and Text by Yen Nie Yong. Yen Nie is a writer and editor based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. More from Yen Nie on www.yongyennie.com. To contact her, please email yyennie[at]gmail[dot]com.

Share

Comments 5

Pingback: Review of “UNPACK-REPACK: Archiving & Staging Ismail Hashim” @ NVAG (2015) – writing foto | se asia

Pingback: Notes on Editing: A million ways to edit. One gut feel. | Invisible Ph t grapher Asia (IPA) | 亞洲隱形攝影師

What an interesting guy.

when and where will the exhibition be?

Hi Susan, More info here: https://www.facebook.com/events/1560943864178397/