Portrait of JO (1976). Painting by David Bowie.

Why do we do what we do? It’s dysfunctional

In a 1998 interview with Charlie Rose, David Bowie was asked what satisfaction he gained from completing a painting or piece of music. He answered quiet frankly that for him it was about finishing, and that it was the volatility and emotion of the process, a not particularly pleasant experience, that allured him. Being an artist in any way is a sign of social dysfunction, Bowie added. It’s an extraordinary thing to want to do. The saner, more rational approach to life to do is to survive steadfastly, create a protective home and a warm loving environment for one’s family, providing food for them. That’s about it. Anything else is extra. All culture is extra. We only need to eat.

Uncertainty, fear and anxiety rule the headlines and affect world psyche today. Doomsday scenarios of recessions and radical ‘terrorist’ ideologies threatening security and survival are instrumentalised against any form of dysfunction or dissent towards the new normal. It would appear that making art today is more irrational a choice than ever before. Art and expression are increasingly viewed as decadent and frivolous. The latest Freemuse Report says attacks on artistic freedom has almost doubled worldwide in 2015. This points to a global trend. Everyone, everywhere is becoming less tolerant.

The market and commodification of Art can be read as a way of pragmatising individualistic agency and art, and rationalising their purpose. All of life, performance and purpose is financialised, so why shouldn’t art? What greater purpose is there then to feed, thrive and multiply? These are not uncommon arguments from neoliberal camps to those who subscribe to more individual agency. Counter-arguments weaken as we all shift towards the middle-class, a position burdened with more material to gain, and lose. The article “The Death of the Artist and the Birth of the Creative Entrepreneur” by William Deresiewicz laments the institutionalisation of art and the loss of its nobility. William argues the artist as a cultural force is decades out of date. The patron or critic has been replaced by the consumer, and in turn, the birth of the creative entrepreneur producing experiences, rather than objects. But the idea of ‘experience’ is nothing new. In the Web 2.0 days, decades earlier, the mantra of the day for Fast Companies and Change Agents was “Consumer Experience, not Product”.

Further thoughts are shared in “Why All Contemporary Art Is Condemned to Die” by Jonathan Sturgeon. Modern consumption patterns have shifted. Art is merely ephemeral information, scrolled out and into oblivion as a picture would on an instagram feed. Traditional art produced art objects, contemporary art produces information about art events, Sturgeon adds.

VII Photo Agency director and photographer Stephen Mayes seems to agree, at least on the notion of experience over object, and the fluidity of modern consumption. In “Photographs Are No Longer Things, They’re Experiences” Mayes says photography is less about document or evidence and more about community and experience. He attributes it to the proliferation of the cellphone. The cellphone has democratised photography (and art) and detached craft and object, both in production and consumption, as noted too in previous references.

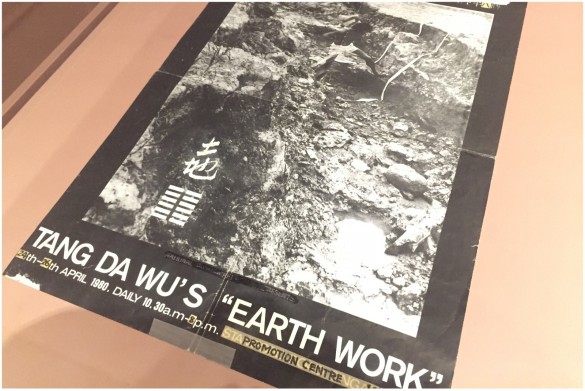

Poster: Tang Da Wu Earthwork (1979)

Picture of photo document, Tang Da Wu Earthwork (1979)

In a TATE conversation about ‘What Makes an Artist?’ with artist Grayson Perry, author Sarah Thornton describes art today as more about Timeliness than Timelessness. Interesting point. Can one be both? Founder of The Artist Village Tang Da Wu’s Earthwork exhibition currently showing at the National Gallery Singapore felt to me it could be.

In a recent review of Laura Poitra’s Astro Noise, Holland Cotter describes how some artists are negotiating this shift “On the one hand, it (art) is flourishing under global capitalism and its new collecting culture. At the same time, its character is shaped by distinctly 21st-century doubts about the moral efficacy of art in a market-intensive, ideal-averse world. In the political thinking of an earlier time, you were either part of the problem or part of the solution, the inference being that there was a solution. The art of the present is not so sure.”

So why ask the questions. Why do we do what we do? What art or photographs do we make? Some might say these questions are as dated and cliched as some of the photographs and art we make.

Photograph of Ai Wei Wei by Rohit Chawla for India Today.

But recent events point to the continuing relevance of such a discourse.

In a speech at the Beijing Forum on Literature and Art in October 2014, President Xi Jinping opines on what he thinks is wrong with contemporary Chinese Art and Culture and what their purpose should really be. At the opposing end, China’s most famed and controversial artist Ai Wei Wei gets mixed responses to his recent art on the Syrian migrant crisis. The recent World Press Photo of the Year is also an image of the same crisis, awarded by World Press Photo where likewise, the role of art is a topic of discourse.

World Press Photo of The Year 2016, by Warren Richardson.

In Malaysia, graphic artist Fahmi Reza was called in for Police investigation over his caricatures of Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak. Indonesia banned, then unbanned photo-sharing Tumblr for objectionable content. The cinema of Apichatpong Weerasethakul responds to the climate in which art and expression navigates in Thailand today. Sonny Liew’s Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye was also subject to question.

The new National Gallery in Singapore, envisioned as a canon for Southeast Asian art, is built on the premise of art discourse. Its presence and effects filter across all spaces in Singapore, including The Substation, currently holding townhall meetings to discuss its identity and future as an art space. In its Artistic Director’s note, Alan Oei identifies four trends in Singapore that The Substation needs to navigate: 1) Artists are careerists (within a professionalised industry; 2) Art market dominates almost everything; 3) Culture is instrumentalised, e.g. for nation-building, or supporting dominant narratives; 4) Globalism effaces the local and particular — is there something to differentiate Singapore? Ironically, the more the government tries to push large scale prestige projects, the more we become one of many along the global circuit.

The Substation’s four points for contention and navigation are very much summarised in the question – why do we do what we do? Interestingly enough, Singapore has recently seen the rise of arguably the country’s most popular and followed photographer and artist, as described by the hundreds of comments left on his pictures shared on social media and tagged (Photo by me).

And Bowie. The Man Who Sold The World. Timeless dysfunction.

Share